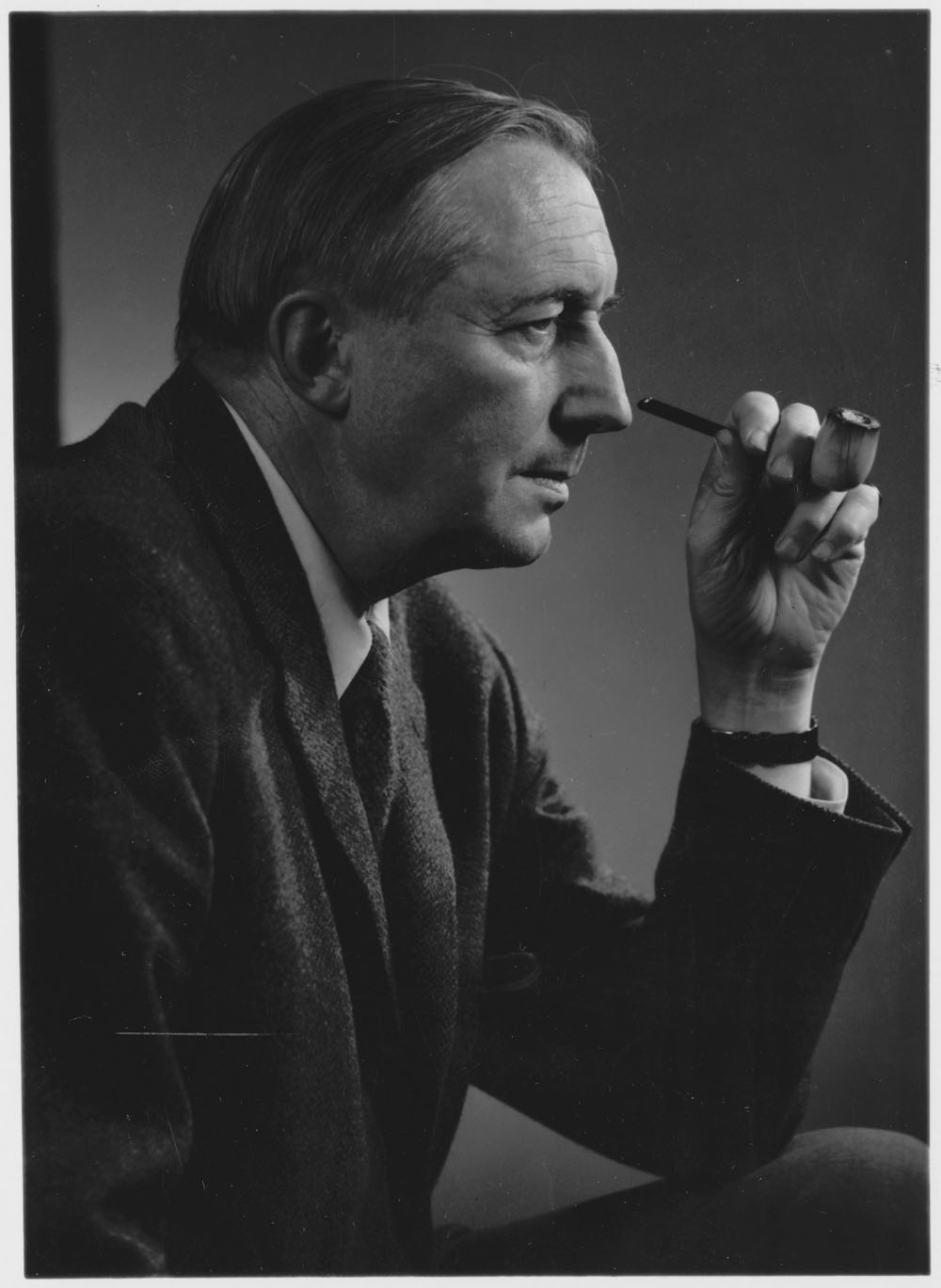

Eugene Alfred Forsey, PC, CC, FRSC, intellectual, senator (born 29 May 1904 in Grand Bank, Newfoundland; died 20 February 1991 in Victoria, British Columbia). Eugene Forsey was known across the country as a scholar, social activist, constitutional expert, senator, and inveterate writer of letters to the press. Forsey helped found the League for Social Reconstruction and the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation in the 1930s. For nearly 25 years (1942–66), he was a director of research for the Canadian Congress of Labour and its successor, the Canadian Labour Congress. He also taught at McGill University, Carleton University and the University of Waterloo and was chancellor of Trent University (1973–77). Forsey was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and was appointed to the Senate (1970–79), named to the Privy Council (1985), and made a Companion of the Order of Canada (1988).

Early Life and Education

Eugene Alfred Forsey was born in Grand Bank, Newfoundland (which had not yet joined Confederation; see Newfoundland and Labrador and Confederation). After his father died, Forsey's mother moved with him to Canada. Forsey was raised in Ottawa in the home of his Quebec-born maternal grandfather, William Cochrane Bowles, a high official in the House of Commons. Growing up in a milieu where literature, politics and religion were the stuff of daily life, the young Forsey eagerly participated in the adults' discussions and excelled in his studies. Family vacations nurtured his love for the lakes and hills of the Canadian Shield, and for the Atlantic coast where his roots went deep.

After receiving an Honours BA from McGill University in Economics, Political Science and English, he earned an MA with a study of the strife-torn Nova Scotia coal industry. He spent three years at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, then returned to McGill in 1929 to teach at the invitation of professor Stephen Leacock.

Social Activism

Soon — to Stephen Leacock's dismay — Eugene Forsey became heavily involved in Canada's burgeoning socialist movement. Appalled by the inequities of the Great Depression, he helped to found the League for Social Reconstruction, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF, later the New Democratic Party) and the Fellowship for a Christian Social Order. Forsey was also one of the authors of the Regina Manifesto (1933). In 1935 he married linguist and teacher Harriet Roberts of Saint John, New Brunswick, who joined him in his activism and his work towards his PhD.

The McGill authorities never liked their young lecturer's politics or his insistence on high academic standards, and in 1941, just as he received his doctorate, they terminated his contract. After a year at Harvard on a Guggenheim Fellowship, Forsey returned to Ottawa as research director of the fledgling Canadian Congress of Labour (later the Canadian Labour Congress), where one of his mentors was the feisty mineworker and fellow Newfoundlander Silby Barrett.

Constitutional Expert

Eugene Forsey's PhD thesis, published in 1943, attacked Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King for his 1926 attempt to avoid defeat by having Parliament dissolved. (See King-Byng Affair.) The Royal Power of Dissolution of Parliament in the British Commonwealth established the activist CCFer as a force to be reckoned with on constitutional matters. It also cemented his remarkable bond with former Conservative Prime Minister Arthur Meighen, King's political nemesis.

Trade Union Researcher

Over the next quarter century, Eugene Forsey worked as a "trade union civil servant," building the Congress's research capacity, pioneering its government relations and public education functions and providing the membership with ongoing analysis of events and policies. During those years, he helped Harriet raise their two daughters, taught part-time at Carleton University, published in historical and political journals, served on United Church committees, and ran (unsuccessfully) in elections as a CCF candidate. Between 1958 and 1962 he was also a member of the Board of Broadcast Governors, forerunner of today's media regulator, the CRTC.

Public Critic

Eugene Forsey's over-riding vocation, however, was that of watchdog for the body politic. His criticisms, like his friendships, crossed party lines, and he became increasingly popular as a speaker and commentator. The media loved him for his sparkling wit, his down-to-earth, sensible explanations, and the feistiness of his often-controversial opinions. Those opinions ranged from his denunciations of company unionism to his advocacy of universal public health care; from his eloquent attacks on "pseudo-history" and bad English to his learned defence of the reserve powers of the Crown as essential to parliamentary democracy.

Federalist

A committed federalist, Eugene Forsey "couldn't stomach it" when the CCF's successor, the New Democratic Party, adopted the quasi-sovereignist theory of Canada and Quebec as "two nations" in 1961. He quit the party and spent the next three decades fighting eloquently in both official languages to save and strengthen the progressive, bilingual, multi-cultural Canadian nation he envisioned.

Senator

Eugene Forsey was working on a history of early trade unionism in Canada when he retired from the Labour Congress in 1969. A year later, his friend Pierre Trudeau appointed him to the Senate. For the next nine years, Forsey enlivened Parliament's upper house, contributing his expertise to legislation and committee work, particularly on questions of social justice, democracy, and the constitution. Although he sat as a Liberal to support Trudeau's federalist policies, he often voted against government measures, and in 1982 he resumed his more natural role as an independent critic. For him, principle always trumped partisanship.

Later Career

Eugene Forsey was active in political and academic circles right up until his death in 1991. He was a Skelton-Clark Fellow at Queen's University in the 1960s, a visiting professor at the University of Waterloo in 1969–70, and Chancellor of Trent University during his Senate years. Fourteen Canadian universities gave him honourary degrees; at many of them he delivered the convocation address. Today, several scholarships and prizes honour Forsey's contributions to Canadian public life.

Even after retiring from the Senate, he was consulted so often by politicians of all stripes that he was given an office on Parliament Hill. He presented briefs to parliamentary committees, wrote extensively on constitutional matters, and sent a stream of letters and articles to the academic and mainstream press. His last great public battle was over the Meech Lake Accord, which he saw as a constitutional straitjacket and a threat to Canadian democracy.

Legacy

Throughout his life, Eugene Forsey's politics were based in his religious faith and his concern for humanity and the planet. His 1953 trip to India as co-director of a World University Service seminar gave him lasting international friendships and a heightened awareness of both the inequities and the potentials of this "global village." In his later years he played a modest part in various efforts towards peace, justice and environmental sanity.

Forsey was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, a member of the Privy Council, and a Companion of the Order of Canada. He is remembered as a 20th-century Canadian whose brilliant intellect, principled combativeness and unremitting hard work helped to shape this country.

Citation: Companion of the Order of Canada

A most distinguished political scientist, labour historian and academic, he [Eugene Alfred Forsey] is known as a leading authority on the British North America Act and the Canadian Constitution. His outspoken commentary has graced, enlivened and stimulated discussion wherever he has served during a career which has spanned the political spectrum.

Honours and Awards

Honorary LL.D., University of New Brunswick (1962)

Honorary D.Litt., Memorial University of Newfoundland (1966)

Honorary LL.D., McGill University (1966)

Honorary LL.D., University of Saskatchewan (1967)

Honorary D.Litt., Acadia University (1967)

Honorary LL.D., University of Toronto (1968)

Honorary LL.D., University of Waterloo (1968)

Honorary LL.D., Dalhousie University (1971)

Honorary LL.D., York University (1972)

Honorary D.C.L., Mount Allison University (1973)

Honorary LL.D., Carleton University (1976)

Honorary LL.D., Trent University (1978)

Honorary LL.D., Queen’s University (1979)

Honorary LL.D., McMaster University (1984)

Privy Council for Canada (1985)

Officer, Order of Canada (1968)

Companion, Order of Canada (1988)

Fellow, Royal Society of Canada

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom