Early History – Government Film Bureaus

In the early years of the film industry, the regulation of the film sector in Canada was left to the provinces. They set parameters for film content, exhibition and distribution. At the turn of the 20th century, several provinces went beyond this and established cinema offices. These organizations produced films to boost tourism and attract immigrants.

The Ontario Motion Picture Bureau (OMPB), created in 1917, was one of the most successful provincial offices. It was also the world’s first state-sponsored film organization. The OMPB was involved in producing films and coordinating their distribution. This began under its first director, S.C. Johnson. These films — up to 1,500 reels per month by 1925 — were distributed for screenings at educational, public and religious institutions. However, the OMPB did not keep pace with the industry’s technological advances. By the late 1920s, its distribution structure had become inefficient and irrelevant. In the midst of the Great Depression, the OMPB was a victim of budget cuts. It was officially closed in October 1934.

In September 1918, the federal government created the Exhibits and Publicity Bureau. It was tasked with producing films that promoted Canadian trade and industry. It was the first national film production unit in the world. The organization’s name was changed to the Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau on 1 April 1923. It produced short informational films, such as the series Seeing Canada, and distributed them across Canada and abroad. In the 1920s, the Bureau had the largest film production studio in Canada. Bureau productions were distributed across the Commonwealth, to European nations like France and Belgium, the United States, Japan and China. It mainly distributed films for non-theatrical screenings. Some of its films were also shown in theatres.

The Bureau succeeded in running a large production unit and distribution network. However, it was not interested in expanding its operations to establish a domestic film industry. Indeed, it discouraged such a move. Instead, it supported the view that Canada should be part of the American film industry. Raymond Peck, the Bureau’s director for much of the 1920s, had close ties with Hollywood. He worked to bring American investors and film companies to Canada. Like the OMPB, the Bureau failed to keep up with technology (it didn’t produce sound films until the mid-1930s). It also struggled through financial difficulties brought on by the Depression. It was absorbed into the National Film Board (NFB) in 1941.

Vertical Integration of the Film Industry

Distribution was the last of the three branches of the film industry to develop. But it quickly came to dominate the industry’s economic structure. By the early 1920s, the largest American distributors had acquired production companies and theatre chains. These acquisitions created vertically integrated combines. This enabled the majors to dominate both the American and the international film industry.

Why is Canada Part of the US Domestic Market?

The federal government did little to boost, or even safeguard, Canada’s feature film industry. In fact, Canadian companies began to structure themselves after the successful, vertically integrated American model. For example, in the early 1900s, the Allen Amusement Corporation obtained exclusive rights to films from Pathé, Independent Motion Pictures and later Paramount Pictures. As a result, by 1920, the Allen Theatres chain was the largest in Canada.

However, in 1923, American-born N.L. Nathanson, owner of the Toronto-based Famous Players Canadian Corporation (FPCC), bought all 53 of the Allen Theatres. This made Famous Players the largest theatre owner in Canada. It now controlled the Canadian exhibition market. Adolf Zukor, head of Paramount Pictures, then acquired direct control of Famous Players through a holding company.

In 1924, the Motion Picture Exhibitors and Distributors of Canada (MPEDC) was created. Its mandate was to protect American film industry interests. It was known as the Cooper Organization, after its president, John Alexander Cooper. The organization took its direction (and funding) from the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA). The Cooper Organization ensured that American industry practices were cemented in Canada. These included discriminatory methods (such as requiring cash in advance) aimed at curbing the success of independent exhibitors.

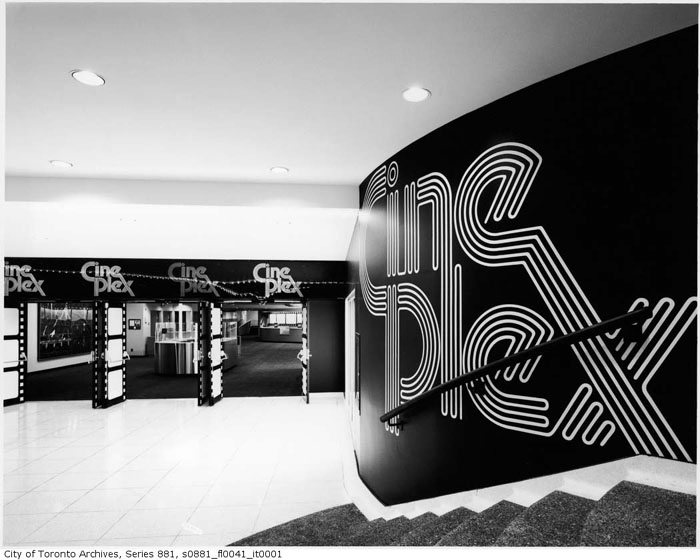

In short order, Canadian box office revenues were incorporated as part of the US “domestic” market. Foreign companies overwhelmed the Canadian distribution and exhibition sector. The major Hollywood studios acquired control of the country’s two largest theatrical chains: Famous Players and Odeon Theatres (now merged as Cineplex Entertainment). This ensured a steady flow of Hollywood films into Canadian theatres.

As early as 1923, Canada had no real, viable film industry of its own. By 1930, American film distributors controlled almost 95 per cent of film distribution in Canada.

Investigation of the American Monopoly

An investigation of the American monopoly in Canada’s film sector began in September 1930 under the Federal Combines Investigation Act. Prime Minister R.B. Bennett appointed Peter White to investigate more than 100 complaints against American film interests in Canada. White’s report concluded that the Famous Players combine was “detrimental to the Public Interest.”

The provinces of Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta and BC took FPCC and the CMPDA to court in Ontario. After a lengthy trial, FPCC and other defendants were found not guilty on three counts of “conspiracy and combination.” The Cooper Organization re-structured in 1940. It removed all exhibitors and re-named itself the Canadian Motion Picture Distributors Association (CMPDA). It continues to represent American and Canadian distribution interests in Canada as the Motion Picture Association–Canada.

Establishment of the MPEAA

In 1946, the Motion Picture Export Association of America (MPEAA, now MPAA) was founded to promote Hollywood productions. The original vertical combines of the majors were broken up in 1948 under US antitrust legislation. But the basic operating principle continued. Most of Hollywood’s production is still controlled, and generally financed, by the major studios. Vertical integration and distributor-controlled production have continued to impact the viability of the Canadian film industry.

National Film Board

The National Film Board of Canada (NFB) was established on 2 May 1939 under the National Film Act. Its mandate was to produce and distribute Canadian-made films that help Canadians better understanding their country. The NFB was originally created as an advisory board to the Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau. But the NFB transitioned into film production during the Second World War. It absorbed the Government Motion Picture Bureau in 1941.

Under the leadership of film pioneer John Grierson, the NFB expanded the distribution system set up under the Bureau. It centralized the supply chain in order to reach the greatest number of viewers. Grierson was particularly interested in having NFB films in the commercial distribution chain. He negotiated a distribution deal for NFB shorts to screen as part of The March of Times newsreel series in the US, as well as in South American newsreels. Another had Famous Players Canada distributing NFB productions to hundreds of its theatres. The NFB also distributed its films through Canadian embassies and consulates.

The main avenue for the domestic distribution of NFB films was its non-theatrical “circuits” system. This had been created by the Bureau. The circuits system distributed films via rural, industrial and union contacts. This eventually resulted in the creation of film libraries. These became the centre of the NFB’s postwar distribution system.

Canadian Cooperation Project, 1948–58

The NFB quickly drew the ire of the American film industry, which worked hard to protect its control over Canadian distribution. In 1948, the Canadian government announced the Canadian Cooperation Project (CCP). This was an agreement with the major American film studios. They promised to increase the “Canadian” presence in their films and distribute more Canadian films in the US. But this was only if they continued to have untaxed and unrestricted access to Canadian theatres. The NFB’s new commissioner, Ross McLean, believed the MPEAA was simply trying to prevent the Canadian government from instituting film quotas. These had been discussed in Parliament. McLean also believed that a percentage of MPEAA profits should be reinvested in the Canadian feature film industry.

The MPEAA argued that the NFB was using government funds to compete with private companies. It was also accused of being too left leaning because of its employment of alleged communist sympathizers. This was a particularly potent criticism in the early days of the Cold War. The NFB survived the MPEAA’s efforts and several lean periods of reduced government investment. For many Canadians, the NFB represents a viable, alternative system for film production and distribution in Canada.

The Bassett Report, 1973

Canadian filmmakers have fought since the post-war years for government protection of the film industry. The Canadian Film Development Corporation (CFDC) — created in 1967 and reorganized as Telefilm Canada in 1984 — saw the film industry as a cultural imperative. Other government agencies took the same approach. They worked to challenge American control over distribution and exhibition.

In the early 1970s, the CFDC came under public pressure to raise the visibility of its films. Various approaches were proposed. One was to legislate the marketplace to ensure wider distribution and exhibition of Canadian films. Another was to use foreign talent alongside Canadians. Broadcasting executive John Bassett was appointed to study the Canadian film industry. The conclusion of the Bassett Report was that “a basic film industry exists. It’s the audiences that need to be nurtured through theatrical exposure. The optimum method of accomplishing this is to establish a quota system for theatres.”

In 1973, a group called the Council of Canadian Filmmakers urged the Ontario government to follow the recommendation of the Bassett Report. Instead, in 1975, Secretary of State Hugh Faulkner negotiated a voluntary quota agreement with both Famous Players and Odeon Theatres. The chains would devote a minimum of four weeks per theatre per year to Canadian films. They would also invest a minimum of $1.7 million in film production. Compliance with the quota was lukewarm at best. Within two years, it had virtually disappeared.

Quebec Cinema Act, 1983

In the 1980s, governments tried using legislation to combat American control. The goal was also to try and keep Canadian distribution and exhibition profits in Canada. In 1983, the province of Quebec passed the Quebec Cinema Act. It required distributors not already operating in Quebec before December 1982 to be located in the province in order to receive a licence. All distributors in Quebec were also required to reinvest at least 10 per cent of revenues in films made in the province.

The Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) was anxious that the protectionist legislation would set a precedent. It threatened to pull its pictures from the province’s screens. In response, the Quebec government deferred the reinvestment stipulation to future negotiations. Members of the MPAA with existing operations in Quebec, including the Hollywood majors, received special standing under the Act. They were essentially “grandfathered” into the legislation. But this “principal establishment” condition severely impacted Canadian film distributors. Canadian companies not primarily located in Quebec couldn’t do business in the province without a license. To access Quebec screens, they would have to subcontract distribution to a firm based in the province.

Film Products Importation Bill, 1988

Following Quebec’s initiative, the federal government took steps to address the problems faced by Canadian distribution companies. The new proposal came in 1987 from Minister of Communications Flora MacDonald. The Hollywood majors would be allowed to distribute any films in Canada for which they owned world rights. They could also distribute films they had some part in producing. Canadian companies would be able to bid for distribution rights to independently produced films.

These proposals encountered stiff opposition. The MPAA generated intense lobbying in both Ottawa and Washington. When the Film Products Importation Bill (Bill 109) was tabled in June 1988, the original proposals had been watered down. During the free trade negotiations that followed, the federal government agreed to abandon them. The bill was subsequently shelved.

In 1988, the Policy on Foreign Investment in the Canadian Film Distribution Sector was introduced. Drawing on Bill 109, it made Canada a separate distribution market for independent films. It prohibited the takeover of Canadian-owned distribution companies. Canadian distributors could be bought by foreign entities. But the new owner would have to reinvest some of its Canadian profits into Canada’s cultural industries. However, distribution companies that were in Canada before February 1987 were exempt from the policy. This included the Hollywood majors, so business continued as usual.

American Conglomerates

In 2016, there were six foreign-owned distribution companies in Canada: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, Paramount Pictures Corporation, Sony Pictures Entertainment Inc., Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation, Universal City Studios LLC, and Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. They were all members of the Motion Picture Association – Canada. It had changed its name from the Canadian Motion Picture Distributors Association (CMPDA) in 2011. The group describes itself as “the voice and advocate of the major international producers and distributors of movies, home entertainment and television programming in Canada.” Its new name was meant to align the group more closely with its parent company, the Motion Pictures Association of America (MPAA).

In recent years, the Hollywood majors have flouted the 1988 policy. They have increasingly distributed independent films. Trade organizations have called for more government attention to the distribution sector to fight the encroachment of American companies. These trade groups include the non-profit Canadian Association of Film Distributors and Exporters (CAFDE, established in 1991). Part of this push includes lobbying governments to change the definition of distribution to include new digital platforms. It also calls for better funding strategies for prints and advertising (key expenses in film distribution). These would encourage reinvestment in the marketing — and production — of Canadian feature films.

Independent Canadian Distributors

Independent Canadian distributors lack access to the two domestic theatre chains and to major Hollywood films. They have typically emphasized the marketing of independent films, low budget movies and art house films. They have also been the main distributors of Canadian films. Many were members of the now defunct Association of Independent and Canadian-Owned Motion Picture Distributors (1977–2015) and the CMPDA.

Many Canadian entertainment companies have followed the vertically integrated model. These include eOne Entertainment, Alliance Communications (later Alliance Atlantis and now Alliance Films), Cinépix (now Lionsgate) and Astral Bellevue-Pathé (now Astral Media). They finance television productions and/or market their films to specialty television channels. Independent distributors include Mongrel Media (established in 1994) and Ron Mann’s Films We Like (established in 2003). Mongrel Media is the exclusive Canadian distributor for Sony Pictures Classics.

Revenues from movies distributed by Canadian companies take a minimal share of the domestic market. In 2011, Canadian companies were responsible for distributing more than 76 per cent of all films released in Canada. However, that same year, foreign-owned distributors took 77 per cent of Canadian box office revenue. Also, when territorial rights for Canada are sold internationally, Canada is generally included in a North American package with the US and bargained for in US dollars.

In 2015, all the Top 10 Canadian box office spots were taken by American releases. Canada contributed $988 million to Hollywood profits. The state of film distribution in Canada is still very much an industry and government concern. The latest Parliamentary review occurred in June 2015. With the film industry’s power consolidated in distribution, the sector has accrued significant power to determine what films make it to the screen.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom