Fraser River Gold Rush

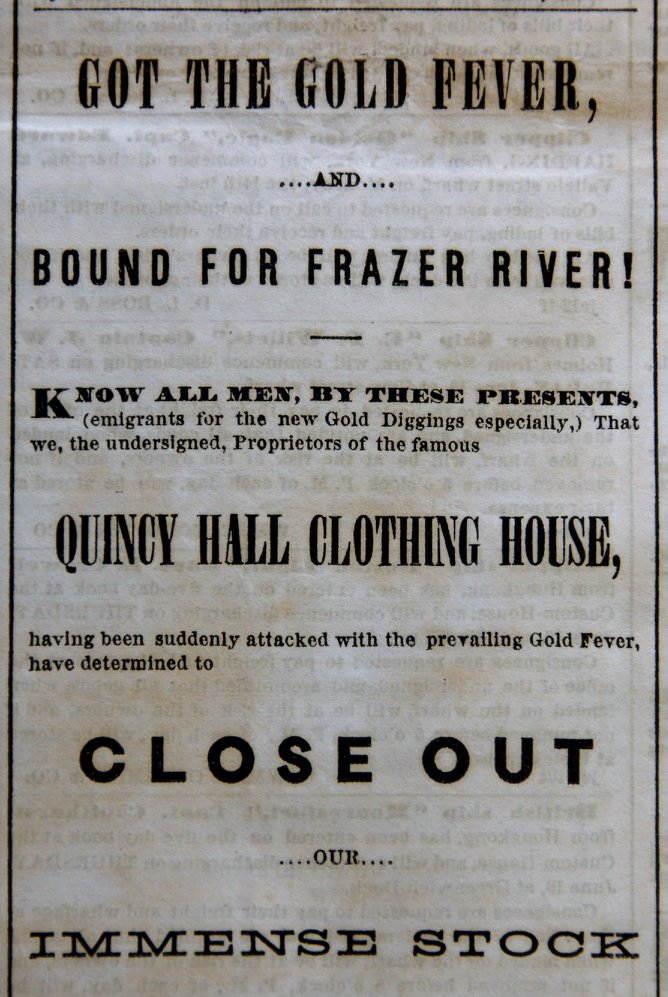

An 1858 advertisement from a San Francisco newspaper claimed that merchants had succumbed to Fraser River “gold fever.”

(courtesy Daniel Marshall)

Background

Prior to 1858, the population of New Caledonia was between 40,000 and 50,000 people, mostly Indigenous peoples. Europeans had arrived in the late-18th and early-19th centuries. Britain established Fort Victoria in 1849 to assert its sovereignty in the West after the loss of territory in the 1846 Oregon Treaty, which established the American/British boundary at the 49th parallel.

News of gold strikes in the Queen Charlotte Islands (now Haida Gwaii) trickled out in 1850, sending the first stream of miners to the area. There were only a few hundred settlers at Fort Victoria on Vancouver Island. Most of them were employed by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC).

The population of Fort Victoria doubled overnight with the influx of miners, but the HBC was not especially welcoming. They wanted little to do with anything that would upset the fur trade’s delicate balance and attempted to suppress any news of gold strikes. Sir James Douglas announced that the unauthorized removal of gold would result in criminal and civil prosecution. By 1852, miners had been driven out of Haida Gwaii by the local Indigenous peoples.

Spring of 1858

Unlike the Cariboo Gold Rush (1861–67), which attracted many Canadians, the Fraser Rush was an extension of California mining society. By the 1850s, placer mining in California had depleted free gold. Miners accustomed to the glory days of the California Rush were marginalized by capital-intensive hydraulic mining. For this large, unemployed class of miners, news of any gold strike “was enough to send hundreds of men into the wilderness to make their fortunes or to die in the attempt,” as miner Thomas Seward wrote.

Gold was first discovered in the Thompson River by a member of the Shuswap (now Secwepemc) nation in 1856. The presence of gold was kept secret until a sample of 800 ounces was sent to San Francisco in February 1858 for assaying. In March, newspapers in Washington and Oregon printed reports of gold discoveries on the Fraser River. Sir James Douglas, HBC governor and the sole authority on the West Coast, proclaimed the Crown’s authority and announced a system of mining licenses.

![“Ho! For Frazer River” [sic] “Ho! For Frazer River” [sic]](https://d3d0lqu00lnqvz.cloudfront.net/media/new_article_images/FraserRiverGoldRush/512px-Peep_at_Washoe_-_Ho%21_For_Frazer_River.jpg)

“Ho! For Frazer River” [sic]

Illustration by J. Ross Browne from "A Peep at Washoe" in Harper's Monthly Magazine, December 1860.

(courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

When newspapers in California picked up the story, a gold frenzy took hold of San Francisco’s population, triggering a sudden mass migration by land and sea, bound for the Fraser River. The first wave of about 400 miners from California arrived in Fort Victoria on 25 April 1858. Between May and June, some 10,000 American miners (mostly of European descent, though some were Hawaiian, African-American and Chinese) travelled by boat up the Fraser River past Fort Langley into the narrow lower reaches of the Fraser Canyon. The total number increased to 25,000 by the fall and to around 50,000 (possibly more) the following year. About 80 per cent of the miners came from California. Yale, just downriver from Nlaka’pamux territory and formerly an HBC trading post, was quickly transformed into a cultural centre similar to 1850s San Francisco.

The richest discoveries of fine flour gold occurred between Hope and Yale in the Fraser Canyon. This region was controlled by Americans who provoked conflicts between Whites and Indigenous peoples. North of Yale, waterfalls and steep canyons prevented steamers from further ascending the Fraser River. Miners excluded from the dominant culture in the lower Fraser, such as the Chinese, Chileans, Hawaiians, African-Americans and other ethnic groups, established diggings beyond Yale.

Impact on Indigenous Peoples

All Indigenous lands of the southern interior were invaded by large companies of miners, triggering the Fraser Canyon War of 1858. As the summer wore on, miners disrupted Nlaka’pamux communities. The men mined gold without consulting Nlaka’pamux community leaders for permission, and threatened violence when challenged. Some of the miners committed acts of sexual violence against Nlaka’pamux women.

Most critically, the miners disrupted the Nlaka’pamux salmon fishery, a critical economic activity that took place at the end of each summer. The miners occupied fishing sites and diverted many rivers, creeks and lakes to wash gravel through mining sluices. In the process, they ruined crucial spawning grounds, jeopardizing the future of the salmon fishery. Also, as Dan Falloon has noted, “In addition to the violence, a smallpox epidemic that broke out in 1862 is estimated to have killed between 50 and 75 per cent of the local Indigenous population.”

The Fraser Rush ultimately broke the back of full-scale Indigenous resistance in the region, particularly among the Central Coast Salish, Interior Salish and southern populations of the Tsilhqot’in. When the Nlaka’pamux and miners called a truce to the Fraser Canyon War on 22 August 1858, the Nlaka’pamux agreed to grant miners access to their territories and resources.

Impact on British Columbia

To avoid the lawless conditions of the Californian and Australian goldfields just a few years earlier, the British government was quick to establish New Caledonia as the colony of British Columbia on 2 August 1858. Sir James Douglas also initiated the building of a network of roads through the interior (see Cariboo Road). But the period of prosperity didn’t last long. By the mid-1860s the Fraser Rush collapsed, and British Columbia sank into a deep recession.

See also: The Fraser River Gold Rush and the Founding of British Columbia; Fraser Canyon War; Gold Rushes; Cariboo Gold Rush.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom