Graphic Art and Design

Graphic art and design are 2 branches of verbal/visual communications which include the related callings of commercial art, book and periodical illustration, typography and type design. They come under the title of "applied arts" as opposed to the so-called "fine arts" (including PRINTMAKING) because of their subservience to the message to be conveyed, the object to be sold, or the service to be advertised. In this sense they are first cousins to INDUSTRIAL DESIGN.

More recently, graphics have come under such rubrics as Visual Communications and Information Design. As Richard Hollis writes in Graphic Design: A Concise History (London, 1994), "Graphics can be signs, like the letters of the alphabet or form part of another system of signs, like road markings. Put together, graphic marks ... form images. Graphic Design is the business of making or choosing marks ad arranging them on a surface to convey an idea.

Until the 1870s and 1880s, most art training in Canada was of a severely practical nature, with subjects being limited to technical drawing and watercolour painting for the benefit of draughtsmen, artisans, builders and schoolteachers.

The introduction of commercial art, lithography, engraving, lettering and illustration classes to the curricula of the fine-art colleges founded in Halifax, Québec, Montréal, Toronto, Winnipeg, Vancouver and other larger centres after Confederation answered a demand from printers, newspaper and magazine publishers, and advertising agencies (the first of which was established in Montréal in 1889) for trained artists who could work with typesetters, copywriters and editors in the preparation of a variety of graphic materials involving the use of drawn or painted images and hand-lettered or typeset texts.

At first such functions had been performed by anonymous craftsmen for such formats as the inn sign, the stagecoach and steamship advertisement, the shop-window showcard, the product label, the auction broadside and the agricultural fair poster. These freelancers, who came to be known by the generic term "graphic artists," had to adapt their often self-taught skills to keep pace with the changes that began to take place in the Canadian printing, engraving and papermaking industries when the waves of the European Industrial Revolution reached these shores.

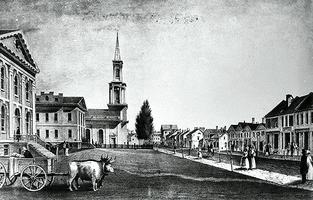

Lithography, invented by Senefelder in 1796, was brought to York [Toronto] by Samuel Tazewell in 1832, and was reintroduced more successfully by Hugh Scobie in 1843. This medium opened new possibilities for book, map and atlas publishers and for the manufacturers of commodities and the promoters of entertainments. It allowed for the reproduction of highly detailed and lifelike scenes and objects, as well as for the more artistic integration of written and pictorial components than did the standard combination of wood-engraving and wooden or metal type.

Subsequent improvements such as the chromolithograph (an innovation of the 1840s) and the steam-driven rotary press made a once-cumbersome and expensive technology competitive with wood- and steel-engraving and their successor, the photographic line and halftone plate. Montréal's William Leggo (1830-1915) put Canada at the forefront of reprographic technology with his invention of Leggotype, patented in 1865 as a photo-engraving process used to reproduce line drawings and engravings. Later extended to cross-line screen work, Leggotype was applied in the reproduction of the world's first magazine halftones, which appeared in the inaugural edition of DESBARATS' Canadian Illustrated News in 1869.

Immigrant Lithographers and Engravers

At first, Canada's commercial lithographers tended to come from Germany (Bavaria being the home of the porous limestone whence the process's name - literally, "drawing on stone" - is based), whereas line engravers were largely British in origin.

Most notable among the latter were John Allanson (1800-59), a student of master wood-engraver Thomas Bewick who arrived in Toronto in 1849, and Frederick Brigden Sr (1841-1917), who served his apprenticeship in London under Bewick's disciple, W.J. Linton, and immigrated to Canada around 1873. His company, the Toronto Engraving Co, changed its name to Brigden's Ltd, and under the directorship of Fred Brigden Jr attracted the services of many talented Toronto artists who contributed drawings to be engraved on boxwood or photo-engraved on metal plates by Brigden employees. (The Winnipeg branch of the firm, headed by Arnold Brigden, employed a number of important figures who went on to careers as painters and teachers - among them Charles COMFORT, Fritz BRANDTNER and W.J. PHILLIPS.)

The importation of skilled engravers and the establishment of domestic firms such as Brigden's, Alexander and Cable, Barclay, Clark and Co, the Canadian Photo-Engraving Co and the Thomson Engraving Co, encouraged newspaper and magazine publishers, and the advertisers on whom they had come increasingly to depend to supplement their subscription revenues, to experiment first with small illustrations, cartoons, decorative headings and vignettes, then with larger and more elaborate ones. The addition of the artist-reporter to the newspaper staff soon followed, with the first practitioners of this new profession - the immediate predecessor of the photo-journalist - usually stepping into their roles from the in-house plate-engraving and layout department.

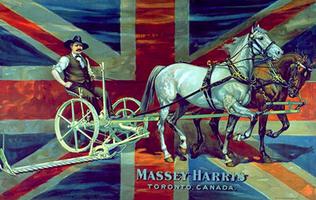

The leader in this diversification process was the art department of the Toronto Globe, which joined forces in the 1880s with the Toronto Lithographing Co, Canada's largest and most advanced litho company, to produce advertising posters and such specialty publications as The Canadian War News (issued weekly to report on the events of the 1885 North-West Rebellion).

Prominent Toronto Litho Co employees included W.D. Blatchly, Henri JULIEN, J.D. Kelly, C.W. JEFFERYS and William Bengough-younger brother of the brilliant political caricaturist J.W. BENGOUGH-who founded the satirical periodical Grip in 1872. Out of this magazine came the commercial-art firm of Grip Ltd, which in the 1900s and 1910s boasted a staff of designer-illustrators who played a key role in the creation of a national school of landscape painting, among them C.W. Jefferys, Tom THOMSON and future members of the GROUP OF SEVEN. Several of these artists followed Grip's inspired art director, A.H. Robson, to Rous and Mann Press Ltd, which specialized in fine commercial typography and presswork, while Franklin CARMICHAEL and A.J. CASSON moved on to the first Canadian silkscreen printing firm, Sampson, Matthews Ltd, founded by artist J.E .Sampson and businessman C.A.G. Matthews.

Toronto Litho Co's leading Toronto rival was the English-born watercolourist J.T. Rolph's engraving and lithography concern. Rolph, Smith and Co merged with Stone Ltd to form Rolph-Clark-Stone in 1917; Grip, meanwhile, evolved into Rapid Grip and Batten, later Bomac Batten, which was absorbed by Toronto's Laird Group.

Montréal lagged behind Toronto as a printing and commercial art centre, and such litho and engraving houses as it supported - eg, A. Sabiston and Co - were run by anglophones who rarely employed French Canadian illustrators or designers. By the turn of the century most medium-sized Canadian cities had their own graphic art establishments, usually connected to a printing company, department store, newspaper or magazine. The separation of forces into commercial art studio, advertising agency, engraver and lithographer came later.

The stodginess and overdecorativeness that marred Canadian graphic art and design were the targets of the younger illustrators who looked to Europe and the US for inspiration. Grip Ltd's F.H. VARLEY and Arthur LISMER had received their training at the Sheffield School of Art and, like J.E.H. MACDONALD, were steeped in the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau design conventions of the era. MacDonald had immersed himself in the principles of English artist and designer William Morris while working in London for Carlton Studios, which had been set up in 1902 by 3 ex-Grip employees (A.A. Martin, T.G. Greene and Norman Price) who would go on to claim that they had introduced the "studio idea" to Great Britain. So successful were they in exporting this Toronto-born concept that by the 1920s they were listed as being the largest such concern in the world.

The Era of Official Propaganda

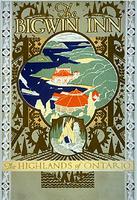

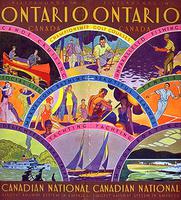

Colour lithographic posters were first used in a federal election campaign in 1891, when the Industrial League hired Toronto Litho Co to produce a series of 4-colour and black-and-white cartoons to support Sir John A. Macdonald's Conservative Party. This established a precedent for the collaboration of governmental and quasi-governmental bodies with advertising and graphic art houses in the production of official propaganda. In the 1890s and 1900s, Sir Clifford SIFTON'S Dept of the Interior, for instance, issued posters in conjunction with the CPR to populate the "Last, Best West," a relationship that persisted into the 1920s. Other transportation companies, such as the CNR and Canada Steamship Lines, were also quick to get into the act.

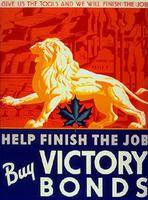

Canada's entry into WWI brought with it a need to co-ordinate recruitment, Victory Bond, "home front" and other campaigns, which resulted in the formation of the War Poster Service, responsible for publishing material for national distribution. Private printing and graphic art firms, such as Toronto's Rous and Mann Press and Montréal's Mortimer Co Ltd, benefited from this work, which generally involved the designing and printing of colour lithographic posters, billboards and press advertisements.

Similarly, during WWII, the National War Financing Board was set up to sell Victory Bonds; the director of Public Information cautioned that "loose lips sink ships"; and the National Film Board issued striking posters (many designed by "Mayo," as Montréal's Harry Mayerovitch signed himself) to advertise the documentaries it produced for the Wartime Information Board, successor to the DPI. Among the Canadian designers and illustrators who lent their talents to these intensive campaigns were Leslie Trevor, A.J. Casson, Eric Aldwinckle, Albert Cloutier, William Winter, Alex COLVILLE, Philip SURREY, Rex Woods, J.S. Hallam, A. Bruce Stapleton and Henry Eveleigh.

The tradition of the painter turning to commercial art, illustration or typographic design to finance his or her fine-art career continued with Bertram BROOKER, Carl SCHAEFER, Clare Bice, Fred J. Finlay, Jack McLaren, John A. Hall, Jack BUSH, Oscar Cahén, Harold TOWN and, into the early 1960s, Joyce WIELAND, Michael SNOW and Louis de NIVERVILLE. Graphic designers, commercial and editorial illustrators and art directors by day, painters by night, by weekend and holiday, these were the anglophone counterparts of the Québécois artists whose livelihoods were provided by church commissions and teaching jobs in art colleges. This splitting of energies prevailed in Canada at least up to the 1960s, when the CANADA COUNCIL and the provincial arts councils introduced the grant system, which released artists from their servitude to applied art. In their place arose a class of professionals for whom design was not a begrudged avocation but a full-time occupation.

Graphic Design Developments Since WWII

The late 1950s and 60s saw an influx of designers and teachers of design from Europe, Great Britain and the United States, who brought with them the advanced styles, techniques and theories associated with international modernism, as originally espoused by the Bauhaus and De Stijl movements; the revived and updated asymmetric typography of Jan Tschichold; and the grid system and the sans serif typography preferred by the Swiss and German leaders of the field.

These modes soon found their way not only into the art schools of the principal ports of entry-Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver and Halifax-but into the design departments, commercial art studios, advertising agencies, and typesetting and printing establishments which employed their graduates. If a certain rigorous uniformity became the national norm, local variations continued to emerge and occasionally to thrive, offering diversity and stimulating experimentation.

Among the European-born designers who came to prominence in Canada during the 1960s and 70s were Peter Bartl, Horst Deppe, Gerhard Doerrie, Fritz Gottschalk, Rolf Harder, Walter Jungkind and Ernst Roch. Montreal and Ottawa were especially favourable to their reformist vision, as can be seen from the rise of such Québécois practitioners as Georges Beaupré, Laurent Marquart, Pierre-Yves Pelletier and Jean Morin.

In Toronto, the British typographical tradition informed the contributions of Carl Dair, Clair Stewart, Allan Fleming, Leslie Smart, Carl Brett and John Gibson. Fleming's work at Cooper and Beatty and later at U of T Press set a standard that inspired his colleagues and successors at the press, including Will Rueter and Laurie Lewis, to similar heights, while Frank Newfeld (also an illustrator) and V. John Lee at McClelland & Stewart, Peter Dorn at Queen's U Press, and Robert Reid and Ib Kristensen at McGill U Press (now united as McGill-Queen's UP) also encouraged academic and commercial publishers to take an interest in "the look of the book." Fleming, who also set his stamp on the national psyche with his elegant logotype for CNR, argued for a design style that took the best from international modernism without overshadowing the humanism and humour that he saw as being particularly Canadian traits.

The Society of Typographic Designers of Canada (TDC) was founded in Toronto in 1956 by four English emigrés - Frank Davies, John Gibson, Frank Newfeld and Leslie (Sam) Smart - to exhibit, encourage and publicize the best Canadian design and designers. With a nod to history, the first meeting of the Society was held at the Arts and Letters Club, the old home-away-from-home of the Group of Seven and their artist/designer colleagues.

Its first exhibition, "Typography '58" (sponsored, like all of its successors, by the Rolland Paper Co.), was divided into three sections: Canadian book design, business printing design, and magazine design, though the emphasis was on the first of these categories. As announced in the catalogue of "Typography '59", the TDC's three aims were: "One, to build up a professional status by accepting professional responsibilities; two, to encourage printers, publishers and others to help them in their efforts towards higher standards in printed communications; and thirdly, to increase public awareness of the benefits which we all derive from good design and craftsmanship." Legally incorporated in 1958, the TDC instituted a fellowship program in 1960 to honour "a designer or individual who by influence and/or accomplishment has made a major contribution to graphic design in Canada."

In response to proddings from the TDC, the federal government established the Design Council and Design Canada in 1961 nationally to promote design, design education and design/industry partnerships through publications, exhibitions and research. Meanwhile, the TDC continued to hold its annual Typography exhibitions, through which the increasing professionalization and internationalization of graphic design in Canada can be traced.

This trend led Allan R. Fleming to acknowledge, in the catalogue of the Typography '64 exhibition, the influence of continental European designers, "For we have grown, and the Rochs, Harders and Doerriés of this world have fed and nurtured us." However, he also cautioned that this "international style," characterized by the ubiquitous use of sans-serif types like Helvetica and Univers and the pursuit of an impersonal "corporate" or "institutional" look, militated against the emergence of a specifically Canadian design identity.

Others saw the comparative brevity of Canada's cultural history as an opportunity to create a new, hybrid sensibility that would take from the old only that which could be adapted to contemporary needs and purposes. At any rate, throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s, designers continued to communicate their sense of national identity through imagery rather than through the development of a definitively "Canadian" manner of handling type, lettering, layout and colour.

In reflection of the prominence attained by all types of design in the hugely successful Expo '67, the Society changed its name to the Society of Graphic Designers of Canada/Société des graphistes du Canada (GDC/SGC) in 1968 and organized itself on national lines in 1974 with funding from Design Canada. Chapters were formed across the country the following year, and letters patent were filed and a National Charter granted in 1976. In 1988 the GDC mounted an exhibition honouring its founding members at the Berthold Type Centre, Toronto.

As of 1994, the GDC/SGC Fellows so far to have been named are as follows: 1966: Carl Dair (d. 1967), Allan Fleming (d. 1977), Leslie Smart, H.L. Rous (Hon. Mem.); 1975: Carl Brett, Gerhard Doerrié (d. 1984), Peter Dorn, Burton Kramer, Laurie Lewis; 1977: Giles T. Kelly; 1983: Peter Bartl, Eiko Emori, Walter Jungkind, Jan van Kampen, Jules LaPorte (Hon. Mem.), Anthony Mann, Neville Smith, Ulrich Wodicka, Chris Yaneff; 1985, Jorge Frascara, Rolf Harder, Charlie Harris (Hon. Mem.), Paul Haslip, Bardolf Paul, Ernst Roch, Denise Saulnier, Gregory Silver; 1987: John Gibson, Tiit Telmet; 1990: Frank Davies, Horst Deppe, Judith Gregory, Frank Newfeld; 1994: Don Dixon, Michael Maynard. (As the scarcity of female names suggests, graphic design was slow to admit women into its upper ranks and inner circles, a situation that has improved in recent years, as the GDC/SGC national membership directory indicates.)

The independent Société des graphistes du Québec, founded in 1972, is more tightly knit than its anglophone counterpart. This is a reflection of the relative size and cohesiveness of the province's design community, but it, too, shows the effects of the influx into Quebec of allophone designers bringing an international perspective into what had been a relatively insular, if European-biased, community. More than elsewhere in Canada, government design initiatives, intended to create an independent "national" image for the promotion of Quebec at home and abroad, have helped to keep the industry afloat during tough economic times.

The 2 events that brought Canadian graphic design into the second half of the 20th century were EXPO 67 and the 1976 Montréal Olympics. Director-general of graphics and signage for La Compagnie de l'Exposition de 1967's graphics and signage program was Montréal's Georges Huel, who designed the official Expo poster, while Guy Lalumiere was responsible for the posters for the cultural pavilions and Julien Hébert devised the official "Man and his World" symbol. Other designers employed by the Canadian Government Expositions commission, for a wide range of publications, signage and identity programs, included Paul Arthur, Burton Kramer, Frank Mayrs and Neville Smith, the latter two of whom worked on the interior of the Canadian Pavilion at the 1970 Osaka World's Fair. Toronto's Paul Arthur devised Expo's effective wayfinding system.

The decision to use Adrian Frutiger's "Univers" typeface resulted in a modernist uniformity that either benefited or marred, according to one's point of view, the graphics program of the XXI Olympiad. Georges Huel, director-general of l'Organisation des Jeux Olympiques (COJO), hoped to use the occasion to "show...that with good planning, the right people involved in design can really contribute to an event like our Games." Among these "right people" were such Montrealers as Huel himself, who took care of signage, furniture designs, uniforms, etc.; P.-Y. Pelletier, who acted as deputy-director in charge of all printed material; and Fritz Gottschalk, who headed the Design and Quality Control Office. In all, COJO commissioned the services of 8 permanent designers and over 100 freelancers.

If nothing else, Expo and the Olympics brought into prominence Quebec's graphic design talent bank, as represented by the likes of Pierre Ayot, Raymond Bellemare, Yvon Laroche and Guy St-Arnaud, in addition to the Italian-born maverick Vittorio Fiorucci, who silkscreened his own posters when his designs were rejected by COJO. As with the controversial Corridart protest, this initiative typifies the flourishing of anti-official creativity which such grandiose events can stimulate.

The 1960s and 70s were also marked by the formation of a number of influential graphic design partnerships: for instance, Rolf Harder and Ernst Roch's Design Collaborative, Penthouse Studio and Studio 2+2, in Montréal; Gottschalk and Ash, Graafiko, Fleming and Donoahue, Burns and Cooper and Eskind-Waddell, in Toronto; and MacDonald, Michaleski and Associates, in Winnipeg. While some of these firms have broken up, new affiliations have since been established, though the trend of the late-1980s and 1990s has been to more flexible, less agency-like houses that allow designers to make personal statements and either specialize in areas of expertise and preference, or range widely over the entire design spectrum.

While older and larger firms still flourish (largely on corporate and government work), younger and smaller companies (many one-person, owner-operated) continue to emerge.

Often the less commercially oriented enterprizes concentrate on cultural commissions, such as exhibition brochures and catalogues, books, posters and reports, but some are branching out to other applications and media, such as the designing of postage stamps, CD covers, videos and computer interfaces. This adaptiveness reflects the impact of the revolution that was ushered in with the advent of computerized typesetting in the 1970s, and subsequently of such technologies as computer-assisted design, laser printing, digital scanning and desktop publishing, which are revolutionizing the profession and calling for new approaches to design for the so-called Information Age.

At the same time, the attendant need to maintain basic standards of legibility and visual clarity has placed new emphasis on design for the more traditional print media. Ironically, some of the best (and worst) graphic design in recent years has come out of public art galleries and museums, though few such institutions today can afford to support their own in-house design departments and tend to rely on freelancers.

For instance, the Art Gallery of Ontario has produced some award-winning catalogue, poster and signage designers over the last three decades, in the persons of Scott Thornley, Richard Male, Marilyn Bouma-Pyper, Steve Boyle, Kevin Connolly and Lisa Naftolin. Other visual arts institutions noted for their dedication to superior publications are Montréal's The Canadian Centre for Architecture, Toronto's The Power Plant, the Winnipeg Art Gallery, and Lethbridge's Southern Alberta Art Gallery.

Typographic design integrity continues to be defended, meanwhile, against trendiness and clutter by such private-press and fine-printing luminaries as Coach House Printing's Stan Bevington, Hemlock Press's David Clausen, Giampa Textware Corp.'s Gerald Giampa, Imprimerie Dromadaire's Glenn Goluska, Dreadnaught Design's Robert MacDonald, Canadian Art's John Ormsby, Aliquando Press's Will Rueter, and the late Ed Cleary, of the venerable Cooper & Beatty Typographers and the more recent Font Shop. As their work serves to remind us, the "democratization" of type and print through desktop publishing software and hardware, and the attendant access of thousands of typefaces, increases rather than decreases the need for taste, discernment and restraint to be brought to bear on the management of textual and visual materials.

The dramatic changes in communications technology and consumption have paralleled, and perhaps contributed to, the decline of the advertising art directors' clubs that provided a focus for graphic design and commercial illustration and photography in Montréal, Toronto, Winnipeg and Vancouver during the 1960s and 1970s. Initially, at least, they served to reward and encourage innovation and quality through annual juried exhibitions and publications. Recently, the former Art Directors' Club of Toronto was renamed the Advertising and Design Club of Toronto, in reflection of a new adjustment of focus to what also is being defined as "persuasion design," "in distinction from information design."

Another important factor in the creation of a design-educated public is the professionalizing of design in art schools, universities and community colleges and the instituting of degree programs. The graphic design programs of such institutions as Halifax's NOVA SCOTIA COLLEGE OF ART AND DESIGN, Toronto's ONTARIO COLLEGE OF ART AND DESIGN and YORK UNIVERSITY, Oakville's Sheridan College of Art, Edmonton's UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA, and Vancouver's Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design have acted as catalysts within their respective communities, bringing word of international developments, sparking creative responses, and providing a steady supply of trained designers for the national and international marketplaces.

NSCAD, for example, attracts students not only from the Maritimes but from the rest of Canada and abroad, through its active student exchange program, which it operates in conjunction with nearly 40 institutions throughout the world. In addition, the college brings in two distinguished designer/educators to teach for a period of 4 weeks.

Ottawa's attempts to raise public consciousness of all forms of design excellence in the 1970s, through such agencies as Information Canada and Design Canada, were constrained by cutbacks, official indifference or opposition to what many considered a needless expense, as well as by internal strife. However, Ulrich Wodicka and his team were able to collaborate on the creation of a standard signage and identity program for all federal departments through their work with Information Canada and the Treasury Board.

The provinces lag behind in the devising of initiatives that would impose coherence and consistency where now anachronism and incongruity reign. Such programs, if carried out with intelligence and sensitivity, can provide direction to the private sector as well as raise the recognition factor of the agencies, departments and services so identified. But success in this area is dependent on the removal of duplication and confusion at the bureaucratic and administrative level.

Deemed by some non- or inactive members to have fallen into institutionalized irrelevancy in the superheated economic climate of the mid-1980s, the GDC continued to work locally and nationally to achieve its objectives of securing and maintaining "a defined, recognized and competent body of graphic designers and to promote high standards of graphic design for the benefit of Canadian industry, commerce, public service and education." (Presumably the arts and communications are included under the "public service" rubric.) Aiding this effort is the society's subscription to "the recognized and accepted standard of ethics, professional code of conduct and responsibility of the International Council of Graphic Design Associations (ICOGRADA)," whose 1991 conference was held in Montréal under the sponsorship of the GDC and the SGQ.

The GDC has found a new mandate for itself as an advocate for the profession in the face of the enormous changes confronting the design and communications industries in the Information Age. In response to the challenges identified by its executive and its membership, the GDC opened a Secretariat in Ottawa in early 1995, reinforcing the national character of the organization and enabling it to increase communications and programming between chapters. Its organ, Graphic Design Journal, is an important source of information and provides a forum for dialogue and the exchange of ideas, not only about the present state of the art but about its history and its future development.

Further, the GDC publishes five regional chapter newsletters, a directory listing its national membership, and various information publications on such topics as ethics, copyright and design education. In cooperation with the Société des graphistes du Québec (SGQ), it sponsors a national design competition.

Realizing that the profession's advancement depends on its forming interdisciplinary networks and forging relationships with the larger design community, the GDC has joined the National Design Alliance (NDA), an advocacy group representing a number of regional and national design-promotion organizations and associations. One of the aims of the NDA is to convince all levels of government, as well as the communications, industrial and business sectors, of the vital importance of all types of design to the welfare of the country. Canada's ability to compete in an intensely competitive, deregulated global economy requires a skilled, flexible workforce and a responsive, effective education and training system.

Such alliances and the partnerships they foster became increasingly critical in the late 1980s and early 1990s as the graphic design community sought to redefine and reposition itself as a leading force in what is now known as communications design. The need for such action became clear in 1988 when the Canadian government conducted a survey of the graphic design business.

The four chief concerns expressed in the responses to the questionnaire were: the impact of new technology on the industry; lack of professional recognition; the quality of graphic design education; and lack of public awareness. If anything, designers seem even more isolated and inadequately prepared for the complexity of their situation, while public awareness of the place of design in daily life and at all levels of culture remains minimal.

Economic factors are largely though not exclusively to blame for this impasse. After what in retrospect were the bountiful 1980s, during which designers could lavish their talents on large-budget annual reports and extensive corporate-identity programs, the profession went through a period of constriction. First to be weathered were the shockwaves caused by the advent of desktop publishing and the availability of off-the-shelf graphics and typographic software packages. The recession made these attractive to financial managers eager to cut production costs for advertising, newsletters, brochures, catalogues and other publications and promotional materials.

Meanwhile, a new environmental awareness caused clients to shy away from ostentation in their use of resources. The economic crisis did not affect the West Coast so severely as the rest of Canada, but east of the Rockies studios were downsizing or merging and agencies scrambling for once-secure contracts, especially as advertising continued to desert the print media for television. Designers were confronted with a nexus of pressures including increased expectancy on the part of clients for fast turnarounds, more responsibility for the production end, and smaller staff.

As businesses, government departments and cultural agencies installed computer stations and sent staff to desktop-publishing courses, the "mystique" of design was undermined. Before, designers performed a unique, specialist service, acting as a liaison between the idea for a communication and the printer. Now, borders are blurring between disciplines as software allows designers and illustrators to retouch and manipulate photographs and even to produce multi-media presentations involving sound, motion (film and animation), stills and type. Instead of working in printed, two-dimensional formats, designers must design for the computer or TV screen and, most crucially, for the computer-user interface.

Borders are also blurring at the supply end (typesetters, photographers, illustrators, animators) and at the delivery end (film-stripping, for instance, is being replaced by digital scanning and colour-separation and artwork is supplied on disk for outputting in a variety of formats, from low-end laser copies to high-definition glossy colour reproductions). With all the changes in technology and the way we access and use information, design is being transformed.

Adapting swiftly, designers are finding ways of responding to these new demands, which must be seen not as obstacles or threats but as opportunities if the discipline is to advance. More and more, the communication artist's job is to suggest solutions to problems and to provide access to information through the use of their analytical and problem-solving skills. These aptitudes have become crucial in an age of endemic post-literacy: hence the boom in iconic way-finding systems, for which Canadians such as Paul Arthur (who claims to have coined the term "signage") and the design firms Gottschalk & Ash and Keith Muller and Associates have won international reputations.

Unfortunately, some designers have responded to these challenges not by re-examining their role and function but by promoting the idea of graphic and video design as consumption - in effect "designer design." The results of this misdirection of energies is nowhere more evident than in the plethora of excessively over-designed publications in which layout, typography and imagery supplant content (art exhibition catalogues being among the worst examples). The superabundance of scalable fonts now available in disk form, coupled by the temptation to succumb to the seemingly endless possibilities for image-manipulation offered by computer-assisted design packages, has bred a stylistic eclecticism that discourages legibility, induces confusion and, furthermore, dates quickly.

Although such journals as Applied Arts Magazine and Studio and the annual Creative Source provide a valuable service by supplying information about designers and illustrators and are handy guides to current trends and new processes, their downside is that, by their very nature as outlets for self-promotion, they encourage work that privileges style over substance. The introduction to such outlets of more historical background information and critical commentary should act as a corrective to these excesses.

Although individual designers and design firms regularly receive recognition in the form of awards, citations and publications outside of Canada, the number of Canadian designers who have achieved widespread international visibility remains small, at least in comparison to the country's disproportionately large contributions to the communications industry. A couple of notable recent exceptions are Don Watt of the Watt Group, the international packaging design giant, and Bruce Mau, chief designer of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press's prestigious Zone book series and head of the Toronto-based Bruce Mau Design.

Such successes inevitably spawn imitators whose work, once au courant, soon becomes passé (witness, for example, the widespread cloning of Loblaws Supermarkets Ltd.'s "No Name" brand look, and the computer-distorted neo-asymmetric typography of the late 1980s and early '90s). This copycat phenomenon (also the bane of fashion design and architecture) forces truly original designers to continue to develop and evolve, if only to avoid being rendered old-hat by their own followers. However, change for its own sake has never benefited design, where the classic modernist tenets of less-is-more and truth-to-materials retain their currency.

Another obstacle for Canadian design to overcome is the fact that, despite the globalization of commerce and data-exchange, the industry lacks public recognition and too often is overlooked by governments and business, who still tend to feel that high-profile commissions, especially for signage and identity campaigns, can only be carried out by foreign design firms. Where before this habit of disregarding our own could be attributed to the celebrated national inferiority complex, the rationale today is that in time of tumbling trade barriers, the encouragement of national talent is quaintly irrelevant.

The demonstrated ability of Canadian designers to compete successfully for important jobs needs promotion not only in the literature of the advocacy groups but in the popular media, where design continues to be mistaken for "fashion" or arts-and-crafts when it is covered at all. Forming a picture of how communications design is developing in Canada is rendered even more difficult by the lack of a national design collection that would allow younger and established professionals, as well as students, teachers, scholars and the general public, to find out what has happened and is happening in the field.

The perceived postmodern design crisis has sparked a variety of responses and strategies. One such reaction is the return to the desire manifested by certain individuals and firms to "design everything around us, as if there is nothing that cannot benefit from the order that we aim to impose upon it," as the Toronto designer and writer Will Novosedlik contends. This is in keeping with the "utopian agenda" of designers which dates back at least to William Morris, the Deutscher Werkbund and the Bauhaus. Failing a renewal of standards by the profession itself, a return to cleaner, clearer, less pretentious design will be dictated by market forces and public revolt. Thankfully, a corrective seems to be in the process of setting in, backed by the realization that the call for skill, judgment and taste is, if anything, even stronger in the so-called new media (including and especially desktop publishing and its extension, multimedia) than in the traditional print formats.

From Graphic Design to Visual Communications Design

A number of non-aesthetic issues have emerged as critical in the 1990s. Two of the most pivotal, from the design perspective, are professional accreditation and design education. To address the first of these, in 1992 the Ontario chapter of the GDC set up the Graphic Design Accreditation Committee, made up of representatives from the academic community. The committee conducted an exploratory survey in July 1993 as a first step toward building a consensus on basic issues: the need for professional accreditation; the definition of graphic design as a profession; professional philosophy and responsibility to society; and, finally, choosing a name for the profession. Although the respondents preferred "graphic design" to "visual communication design" by a small percentage, the latter term tends to be favoured by educators over the former.

As in design appreciation, Canada has long lagged behind the other Western nations in the area of design education, and is only beginning to catch up. Gradually, additional subjects such as theory, history, sciences and liberal studies have gained space in degree-granting design education courses. While visual communications remains the core of the curriculum, additional program content has always been a key factor in responding to changing contexts. In the 1980s, the growth of design studies has helped to modify conceptions of design as an interdisciplinary field.

Illustrative of the recognition of the importance of design in daily life is the NSCAD Visual Communication Department, as guided, successively, by Anthony Mann, Horst Deppe and Hanno Ehses. The program - whose graduates receive a Bachelor of Design in Communications degree - stresses both the practical and the theoretical, emphasizing not only visual but written and spoken communication. During the past 20 years the program has pursued a regional, national and international mandate. This holistic approach has paid off: according to a statistical survey, 90% of graduates have jobs which are design-oriented.

To help achieve a repositioning in which learning is a lifelong rather than a finite process, and adaptiveness to change and new challenges are a necessity for survival, Sheridan College and Ryerson University came together in 1994 to lay out plans for the Ryerson-Sheridan Visual Communications Design Degree Program which, if implemented, will be the first of its kind in Canada. By positioning its program in a business and communications context, the learning institution will help the profession to achieve its full economic potential. The rationale for the creation of this program is "to equip students for the rapidly changing professional environment of the 1990s and beyond with integrated, adaptable skills."

Meanwhile, a number of other initiatives have also been undertaken to achieve similar goals, including a federal $450 000 study to assist the Canadian design sector in assessing competitive challenges. Concurrently, the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Trade, in conjunction with various design organizations, launched the Ontario Design Strategy based on the assumption that innovative design is crucial to the success of Ontario business and industry.

What used to be known as graphic design is so omnipresent as to be invisible. This is ironic, because, unlike industrial design, whose practitioners have perennially complained that Canada's is a branch-plant economy, the communications design business is significant, despite this country's relatively small population. This is especially the case in Ontario, which boasts an estimated 1300 graphic design firms (including printers offering a design service), with nearly 12 000 people employed as designers or illustrators, out of a total of about 26 000 in Canada as a whole.

Increasingly, the design business (and its educational component) is becoming more global, with design groups functioning internationally. Design and communications industry leaders agree that the information economy is key to the future of Canada. The Government of Ontario's and the Government of New Brunswick's current sectoral strategies for design, telecommunications, computing and culture recognize this. Professional survival in all the visual communications fields requires not only adaptiveness but a sharing of information uncharacteristic of the competitive nature of the culture. If design is to play any role in the integration of communications technologies that is being heralded in all the media, its understanding of, and conversancy with, all the components that are being "converged" is mandatory. As with works of art and literature, design in the on-line future may depend for its living not on the sale of "originals" and the licensing of rights, but on upgrades and add-ons offered on an individual or subscription basis.

In the midst of all these variables, however, the essential design skills of analysis, information structuring and communication are still central. For multimedia to be content-driven, publishers, editors, writers and designers must take control of this new vehicle rather than allow the definitive decisions to be made by technicians, accountants and sales forces favouring the lowest-common-denominator approach.

Unfortunately, the lack of a common sense of purpose impedes this effort, as does a deficiency of reliable reference materials, published and unpublished, on Canadian design history. Although the National Archives of Canada has made several moves to fill these gaps through the establishment of such specialist repositories as the National Poster Collection and the Canadian Centre for Caricature (whose 20 000+ holdings are now available on an optical disc imaging system called ArchiVISTA), the usual funding restrictions curb its larger ambitions to acquire, exhibit and publish examples of Canadian graphic design and illustration from all periods. While the NATIONAL MUSEUM OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY collects artifacts relating to the printing trades, it is less interested in assembling examples of the printed object.

Unlike Montréal's Musée des Arts Décoratifs at the Chateau Dufrèsne, the new Design Exchange is not a collecting institution, though exhibitions featuring graphic design may occasionally appear among the displays of products and furniture. Economics and logistics being what they are, the long-overdue museum of Canadian graphic and communication arts is likely to achieve only a virtual reality. An important first step was taken in that direction by Ken Chamberlain, former librarian of the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design, who in 1994 published his long-awaited bibliography of Canadian design, available in both printed and CD-ROM formats.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom