Igor Sergeievitch Gouzenko, Soviet intelligence officer, author (born 26 January 1919 in Rogachev, Russia; died 25 June 1982 in Mississauga, ON). Igor Gouzenko was a Soviet cipher clerk stationed at the Soviet Union’s Ottawa embassy during the Second World War. Just weeks after the end of the war, Gouzenko defected to the Canadian government with proof that his country had been spying on its wartime allies: Canada, Britain and the United States. This prompted what is known as the Gouzenko Affair. Gouzenko sought asylum for himself and his family in Canada. His defection caused a potentially dangerous international crisis. Many historians consider it the beginning of the Cold War.

Background: Canada-Soviet Alliance

Canada and the Soviet Union became allies after Nazi Germany invaded the USSR in June 1941. (See Second World War.) The governments in Ottawa and Moscow agreed in June 1942 to open diplomatic relations. The Soviets soon established their first embassy in Ottawa. From that base, they built a network of espionage and intelligence-gathering agencies. They used and expanded upon assets they already had in the small Communist Party of Canada.

Before the war, there was little about Canada that was of interest to the Soviets. But during the war, Canada played an important role in the Allied war effort. Canadians in sensitive positions were privy to diplomatic, scientific and military secrets. This included highly classified information concerning research on radar, code-breaking and the atomic bomb.

Ottawa had also become a strategic site for the GRU, the Main Intelligence Directorate of the Soviet General Staff. One of the agents Moscow sent to Ottawa in the summer of 1943 was Lieutenant-Colonel Nikolai Zabotin. He had orders to keep his espionage activities secret from Soviet ambassador Georgi Zarubin.

Early Life and Intelligence Career

Igor Sergeievitch Gouzenko was born in Rogachev, Russia, on 26 January 1919. His father died fighting for the Red Army during the Russian Civil War. (See also Canadian Intervention in the Russian Civil War.) Gouzenko met his wife, Svetlana Gouseva, while studying architecture at the University of Moscow. He was still a student when the Germans invaded the USSR. He was conscripted into the Red Army.

Soviet Embassy in Ottawa

Gouzenko was trained as an intelligence officer. He was assigned to GRU headquarters in Moscow, where he worked as a cipher clerk (someone who codes and decodes messages). He had been there for about a year when he was ordered to accompany Zabotin to Ottawa. There, he would handle transmissions to and from Moscow. Svetlana, who was pregnant with their first child, joined him in Canada in October.

The Gouzenkos were stunned to discover that life in Canada was much better than in the Soviet Union. Canadians, even in wartime, enjoyed material comforts that were scarce in the USSR. Gouzenko and his family had their own small apartment at 511 Somerset Street. He later said of it, “In Moscow a place that size would have been shared by four or five families.”

The civil liberties Canadians took for granted — such as freedom of speech, freedom of the press and the right to free and open democratic elections — contrasted sharply not only with the repressive nature of life under Soviet rule, but also with the secretive, oppressive atmosphere of the embassy. Gouzenko later explained that he became disenchanted with his own government as he learned that the GRU and another secret intelligence organization, the NKVD (People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs) were using the embassy as a headquarters from which to spy on their allies. He had also heard people in the embassy talk about the inevitability of war between the Soviet Union and the Western powers.

Gouzenko kept his misgivings to himself. Then in early September 1944, Zabotin suddenly informed Gouzenko that he was being recalled to Moscow, along with his wife and baby son. Gouzenko was alarmed. He still had almost two years to go on his tour of duty. The unexpected recall could only mean that he was in trouble because of some mistake. If he returned home, he feared he could face internment in a labour camp, or even execution. Zabotin was able to have his departure delayed, but Gouzenko knew that sooner or later he would have to return to the Soviet Union and an uncertain fate.

Defection

According to Gouzenko, he and Svetlana, who was pregnant with their second child, decided to defect from the USSR. He said he felt loyalty to Russia, but not to the Communist regime, which he believed had betrayed the Russian people and its Canadian allies. Gouzenko planned the defection carefully. Over time, he copied or stole documents he believed would be of great interest to Canadian authorities. Often, he hid the documents in his clothing as he left the embassy.

On 5 September 1945, he walked out of the Soviet embassy for the last time. That evening and the following day, Gouzenko tried unsuccessfully to seek help at the offices of the Minister of Justice, the Ottawa Journal and the Ottawa Magistrate’s Court. But he either could not make himself understood or his story was not taken seriously. The USSR, after all, was still perceived to be Canada’s ally.

Svetlana accompanied Gouzenko as he moved about the city on 6 September. She had their toddler under one arm and in her other hand a bag full of embassy documents. That night, they hid in a neighbour’s apartment, while the NKVD raided their unit across the hall.

The Gouzenkos’ quest for asylum hadn’t gone unnoticed. Word of it was passed from the justice department to Norman Robertson, the undersecretary of state for the Department of External Affairs. He informed Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King that Gouzenko claimed to have documentation proving Soviet espionage activity in Canada and the United States.

King initially was suspicious of the would-be defector’s motives. He did not want the Canadian government to take any action that the Soviets might deem unfriendly. However, three other officials had also been informed of the situation: William Stephenson, the Canadian head of British Security Co-ordination (BSC); Peter Dwyer, the MI6 representative in Washington; and MI6 director Sir Stewart Menzies. One of those men — likely Dwyer, according to Soviet and Cold War historian Amy Knight — advised King to get Gouzenko and his documents at once.

Early on 7 September, RCMP officers took Gouzenko and his family into protective custody.

Gouzenko Affair

While Gouzenko was interrogated at RCMP headquarters, his documents were being translated. They revealed the existence of a large-scale Soviet espionage system that Robertson told King was, “much worse than we would have believed.” The Soviet embassy was a home to several spies connected to agents in Montreal, the United States and the United Kingdom. They had been providing Moscow with classified information ranging from cyphers to atomic research.

Gouzenko’s defection and the contents of his documents caused enormous concern for the security of Canada and its American and British allies. Leaders at the Soviet embassy were also anxious. Zarubin demanded that the Canadians hand Gouzenko over to him, on the grounds that he was a thief who had stolen money. Canadian authorities claimed not to know where he was and released an RCMP bulletin to RCMP offices across the country.

For their protection, the Gouzenko family was moved to Camp X, a top-secret spy training school near Whitby, Ontario. Representatives of the RCMP, FBI, BSC, MI5 and MI6 continued questioning Gouzenko.

On 29 September 1945, King went to Washington, DC, to confer with President Harry Truman. In October, he went to London for meetings with Prime Minister Clement Attlee and officers of the British secret service agencies MI5 and MI6. The American, British and Canadian leaders faced a delicate situation. They couldn’t tolerate Soviet espionage, but they also did not want to endanger diplomatic relations with Moscow in the uncertain atmosphere of post-war Europe.

News of the discovery of the Soviet spy operation was withheld from the public until 3 February 1946. American journalist Drew Pearson broke the story. The next day, King informed

his Cabinet of the Gouzenko Affair for the first time. He also appointed two justices of the

Supreme Court of Canada to head a Royal Commission on the matter.

Using the War Measures Act as legal justification, the RCMP arrested 39 suspects; 18 were convicted. Among them were MP Fred Rose and Sam Carr of the Labor-Progressive Party (see Communist Party of Canada), and Canadian Army captain Gordon Lunan. In the United Kingdom, nuclear physicists Alan Nunn May and Klaus Fuchs were convicted and sent to prison.

The Gouzenko Affair sparked investigations in the United States that eventually led to the controversial 1953 executions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for treason. (See also Capital Punishment.)

The Soviet government admitted that “certain members” of its Ottawa embassy staff had obtained “certain information of a secret character” from Canadian nationals, but implied that the information was worthless. The Canadian government expelled embassy staff members who were implicated in the affair. Zabotin was recalled to the USSR and sent to a labour camp in Siberia. He was released in 1953.

The Iron Curtain (1947)

In 1948, Twentieth Century-Fox released The Iron Curtain. The film is based on articles Gouzenko published in Cosmopolitan magazine in 1947 about his defection. The movie was shot on location in Ottawa and filmed at many of the locations mentioned in Gouzenko’s telling of events. Timed with the release of the film, Gouzenko published a collection of his magazine articles under the title The Iron Curtain: Inside Stalin’s Spy Ring in the US. The book was published in Canada under the title This Was My Choice.

Later Life

Igor and Svetlana Gouzenko were given Canadian citizenship, new identities and new lives in Canada. They raised eight children. Even though their home in Port Credit, Ontario, was under constant RCMP guard, Gouzenko lived in fear of assassination by Soviet agents.

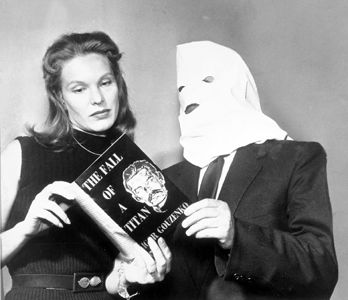

Gouzenko wrote This Was My Choice (a.k.a. The Iron Curtain), a book about his defection published in 1948. He also wrote The Fall of a Titan, a novel about life in Stalinist Russia. It won a Governor General’s Literary Award for fiction in 1954.

Gouzenko made public appearances from time to time, always wearing a hood over his face to protect his identity. The hood became almost a trademark feature.

In 1968, Gouzenko’s appeal in a libel case against Maclean’s magazine was heard by the Supreme Court of Canada.

Gouzenko died of a heart attack in Mississauga, Ontario, on 25 June 1982.

Significance and Legacy

Gouzenko’s exposure of the Soviet spy network in the West is considered by several historians and critics to mark the beginning of the Cold War era. It is seen to have set the stage for the “Red Scare” of the 1950s.

Two plaques, erected in 2003 and 2004, commemorate Gouzenko’s defection. Both are in Dundonald Park, across the street from Gouzenko’s Ottawa apartment. One of them was approved by the federal Historic Sites and Monuments Board. (See Historic Site).

See also Editorial: Igor Gouzenko Defects to Canada; Official Secrets Act; Russian Canadians.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom