A knock on the apartment door froze him in his steps. Another knock, louder, more insistent. The knocking turned to pounding. A voice called his name several times. Finally, the pounding stopped, and he heard footsteps going down the stairs. He knew he needed help.

"He” was Igor Gouzenko, a cipher clerk at the Soviet embassy in Ottawa. It was 6 September 1945, the day after he left the embassy for the final time following weeks

of carrying secret documents home under his clothes. Soviet agents had come to take him in. Gouzenko was protected by three of his Canadian neighbours, who got him and his family to safety, called the police and told the agents when they returned that

the Gouzenkos were away.

Gouzenko asserted that the Soviet Union maintained an extensive spy ring in Canada, aimed mostly at obtaining atomic secrets. Furthermore, Gouzenko warned, the Soviets were not allies but were planning world domination. Gouzenko’s revelations shattered the innocence of the naive Canadian populace. His defection initiated the Cold War between the Soviets and the West and led to the creation of NATO and the Warsaw Pact.

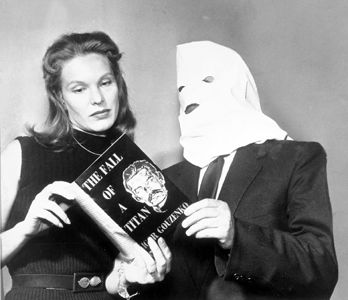

Gouzenko’s autobiography, This Was My Choice, details Russian life under Stalin. The conditions young Igor faced are unfathomable to most Canadians. Deprivation and poverty took its toll on the Soviet people. They were worn down by the cruelty and tyranny of the Communist government; its history includes purges, concentration camps, mass executions and torture.

The apartment in Ottawa where Soviet spy Igor Gouzenko lived.

Growing up, Igor learned to keep his mouth shut, trust no one and do as he was told. A student at Moscow’s Architectural Institute, he was conscripted and sent to the Kuibishev Military

Engineering Academy of Moscow. Distinguishing himself, he was sent to the Higher Intelligence School of the Red Army. As a cipher student learning to decode secret messages, he realized that his access to secrets made him both valuable and dangerous

to the government, a fact that informed his defection.

Gouzenko was transferred to Soviet Military Intelligence (GRU) headquarters in Moscow, where he observed a network of Communist spies from all over the world. He was sent to Ottawa in 1943. In Canada he found a land of plenty, a land he did not want to leave when he learned he would be sent back to Moscow. He also discovered the extensive spy ring operated by Colonel Zabotin.

When Gouzenko left the embassy on 5 September, he knew he had to act quickly before he and the documents were missed. He encountered disbelief and a bureaucratic shuffle as he and his family trudged back and forth between government offices. Fearing for their lives, they returned dejectedly to their apartment. That night, watching men who were watching his apartment from across the street, Gouzenko knew their situation was desperate. He turned to his neighbour for help.

It turned out that the Canadian officials had listened but took the time to check out the allegations. On 7 September, the Gouzenkos were given political asylum. Within a month, they were taken to Camp X, a top-secret spy training school near Whitby, Ontario.

The government’s investigation took months. Using the War Measures Act as legal justification, the RCMP arrested 13 suspects by 16 February 1946. Seven were convicted. On 14 March, 26 other Canadians were arrested for spying, including MP Fred Rose.

Eleven were convicted, 10 acquitted and five set free without indictment.

Among those implicated by Gouzenko’s documents was Egerton Herbert Norman, an External Affairs official hotly pursued by US Red-hunters; and Lester B. Pearson, then secretary of state for external affairs, who ardently protected Norman. Gouzenko maintained that Pearson had Communist leanings, an allegation supported by Elizabeth Bentley, a Soviet double agent who later withdrew her testimony.

Historians argue about the state of Pearson’s loyalty. While some regard Gouzenko as a hero to the West, others accuse him of being a mercenary or a traitor. Gouzenko’s reply would be that he “had a duty to the millions enslaved and voiceless in Russia.” At the very least, he was an opportunist who made a better life for himself and his family, though he did not enjoy the freedom we take for granted. He lived the rest of his life in Mississauga under police protection. He died in 1982.

In the end, what Gouzenko did was pay homage to Canada, democracy and freedom. He risked his and his family’s lives to embrace what we accept as a birthright.

See also Official Secrets Act; Russian Canadians.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom