Internment is the forcible confinement or detention of a person during wartime. Large-scale internment operations were carried out by the Canadian government during the First World War and the Second World War. In both cases, the War Measures Act was invoked. This gave the government the authority to deny people’s civil liberties, notably habeas corpus (the right to a fair trial before detention). People were held in camps across the country. More than 8,500 people were interned during the First World War and as many as 24,000 during the Second World War — including some 21,000–22,000 Japanese Canadians.

First World War

Shortly after the First World War was declared, the federal government passed the War Measures Act on 22 August 1914. It was in effect until 10 January 1920 — the official date of the end of the war with Germany. (See Treaty of Versailles.) The War Measures Act gave the federal Cabinet sweeping powers to suspend civil liberties and to govern by order-in-council. This meant it could make and impose laws without the approval of Parliament.

On 15 August 1914, the government issued the Proclamation Respecting Immigrants of German or Austro-Hungarian Nationality. It authorized the arrest and detention of Canadians from Germany or Austria-Hungary if there were “reasonable grounds” to believe they were “engaged or attempting to engage in espionage or acts of a hostile nature, or giving or attempting to give information to the enemy, or assisting or attempting to assist the enemy.”

According to official records, 8,579 men were held at 24 internment camps and receiving stations across Canada. This included 5,954 men of Austro-Hungarian origin, the majority of whom were Ukrainian. There were also 2,009 Germans, 205 Turks, and 99 Bulgarians. Some dependents of the male internees — 81 women and 156 children in total — were also voluntarily interned. Other internees included homeless people, conscientious objectors, and members of outlawed cultural and political associations.

In 1915, responsibility for internment operations shifted from the Department of Militia and Defence to the Department of Justice. However, Major General Sir William Otter remained in charge.

Around 80,000 people, mostly Ukrainian Canadians, were obliged to register as “enemy aliens” during the war. They were compelled to report regularly to the police and were subjected to other state-sanctioned censures. These included restrictions of their freedom of speech, as well as their movement and association.

See Ukrainian Internment in Canada.

DID YOU KNOW?

The term enemy alien referred to people from countries, or with roots in countries, that were at war with Canada. During the First World War, this included immigrants from the German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires and Bulgaria; during the Second World War, people with Japanese, German and Italian ancestry.

Internees also had their property confiscated. Much of it was not returned at the end of the war. Internees were often made to work on large labour projects, e.g., building a portion of the golf course at Banff National Park. They were used to build roads, clear bush and cut trails. They also worked on logging and mining operations. They were paid less than half the daily wage offered to other labourers.

Conditions were trying. The guards were sometimes brutal. Resentment at what many regarded as their unjust confinement was widespread. This provoked resistance — some passive, such as work slowdowns. Other efforts were more determined. There were escape attempts and even a riot involving some 1,200 internees at Kapuskasing, Ontario, in May 1916. Three hundred armed soldiers were needed to put it down.

In total, 107 internees died in captivity. Six were shot dead while trying to escape. Others succumbed to infectious diseases, work-related injuries and suicide. In many cases, they were buried in unmarked graves or cemeteries far from their communities and loved ones.

Redress

Efforts to gain redress (acknowledgement and compensation) for Canada’s first national internment operations began in 1978. Internee Nick Sakaliuk provided testimony to historians about his experiences as an internee at Fort Henry in Kingston and then in the Petawawa and Kapuskasing camps. Yet almost a decade passed before a campaign to right this historic injustice began. It was led by the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association (UCCLA).

The UCCLA took its cue from another survivor, Montreal-born Mary Manko Haskett. She believed that any redress campaign should be “about memory, not money.” Haskett was six years old when she was exiled to the Spirit Lake camp. Her younger sister Nellie died there.

Haskett believed that contemporary society need not bear direct responsibility for what happened decades earlier. An official apology was never requested. Compensation to individual survivors or their descendants was never sought. The UCCLA instead made concerted efforts to raise public awareness through initiatives such as the installation of historical markers and statues. A trilingual plaque was unveiled by a Spirit Lake camp survivor, Stefa Mielniczuk, at Fort Henry on 4 August 1994.

A $10 million community settlement fund was established in 2008 to further support commemorative and educational projects about Canada’s first national internment operations. Symbolically, the settlement was signed in Toronto’s Stanley Barracks, a “receiving station” for internees from 14 December 1914 to 2 October 1916.

Second World War

The federal government also invoked the War Measures Act during the Second World War — on 25 August 1939. The Act was used to implement the Defence of Canada Regulations. These gave the Minister of Justice the authority to detain anyone acting “in any manner prejudicial to the public safety or the safety of the state.” As a result, both enemy nationals and Canadian citizens were subject to internment.

The army and the Secretary of State shared administrative responsibility for internment camps. More than 40 camps held around 24,000 people in total. A total of 26 internment camps were in Ontario, Quebec, Alberta and New Brunswick. (See also Prisoner of War Camps in Canada.)

Germans

Most of the German Canadian internees were members of German-sponsored organizations. Some were leaders of the National Unity Party (the Canadian Nazi Party). Hundreds of Germans on Canadian soil were accused of spying and subversion.

The camps also housed captured enemy soldiers. More than 700 German sailors captured in East Asia were sent to Canada. German immigrants who had arrived in Canada after 1922 were also forced to register with the authorities; 16,000 did so. (See also Prisoner of War Camps in Canada.)

Italians

After Italy entered the war in June 1940, several prominent Italians were interned. Around 600 Italian men suspected of sympathizing with fascism were placed into three camps: Kananaskis, Alberta; Petawawa, Ontario; and Fredericton, New Brunswick. Some 31,000 Italian Canadians were registered as enemy aliens. They were forced to report to local registrars or to RCMP stations once a month.

Jews

In the summer of 1940, more than 3,000 refugees — among them 2,300 German and Austrian Jews aged 16 to 60 — were sent to Canada. They were interned in guarded camps in Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick. The Jews in the group came to be known as the “accidental immigrants.” They were initially interned in prisoner of war (POW) camps alongside actual POWs, including Nazi Germans. (See Canada and the Holocaust.)

Japanese

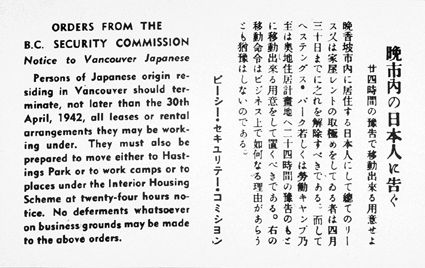

In March 1941, Ottawa required all Japanese Canadians, whether they were citizens or not, to register with the government. This was done on the recommendation of the Special Committee on Orientals in British Columbia, a federally appointed advisory group. In effect, this declared Japanese Canadians to be enemy aliens.

Immediately after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and Hong Kong on 7 December 1941, the RCMP interned 38 Japanese nationals. Later, an additional 720 Japanese were imprisoned; they were mainly Canadian citizens and members of the Nisei Mass Evacuation Group who resisted separation from their families.

DID YOU KNOW?

Various scholars and activists have challenged the notion that Japanese Canadians were interned during the Second World War. Under international law, internment refers to the detention of enemy aliens. But most of the Japanese Canadians involved — 65 per cent — were Canadian citizens. Terms suggested instead include incarceration, expulsion, detention and dispersal.

On 24 February 1942, Cabinet ordered Japanese Canadians to move 100 miles inland from the Pacific Coast. The order led to the expulsion of some 21,000–22,000 Japanese Canadians from their homes. Sixty per cent were Canadian born and 77 per cent were Canadian citizens. They were divided by sex, and housed together on cots in a former women’s building and in livestock barns on the grounds of the Pacific National Exhibition. (See Japanese Canadians Held at Hastings Park.)

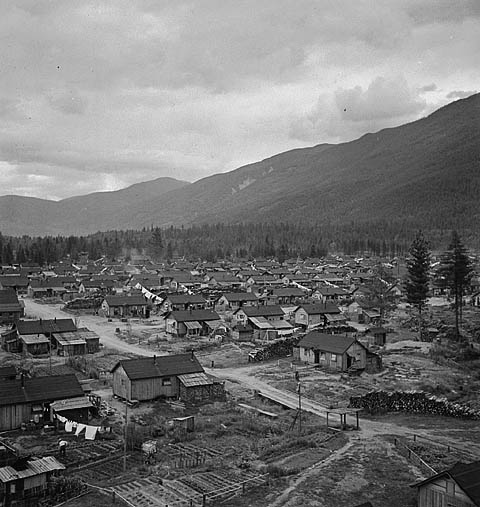

The vast majority of Japanese Canadians were then exiled to the Slocan Valley, in BC’s eastern Kootenay region. They were housed in what were euphemistically called “interior housing centres” in largely-abandoned mining towns (e.g., New Denver, Kaslo, Greenwood and Sandon). Their activities were severely restricted. The Canadian government confiscated and later sold their property; it also pressured around 4,000 of them to accept mass deportation after the war ended.

See Internment of Japanese Canadians; Japanese Canadian Internment: Prisoners in their own Country.

Other Internees

Citizens could be interned for belonging to outlawed organizations, such as the Communist Party of Canada. Because of this, some have claimed that internment was used as a weapon against labour leaders. For example, J.A. “Pat” Sullivan, president of the Canadian Seamen’s Union, was interned in 1940. He was released in 1941, along with about 130 other communists, after the Communist-ruled Soviet Union joined the Allies. Almost 850 Canadian fascists, such as Adrien Arcand of Montreal, were also interned.

In one of the most high profile cases, Montreal Mayor Camillien Houde was arrested at city hall in 1940. He was interned for four years in Ontario for denouncing government policies that would lead to conscription.

During the First World War, Canada had housed 817 internees from Newfoundland and British Caribbean colonies. During the Second World War, Canadian camps held POWs and merchant seamen captured by the British, as well as some British civilians. At the peak in October 1944, Canada held 34,193 persons for Britain. (See also Prison Ships in Canada: A Little-Known Story; Prisoner of War Camps in Canada).

Redress

In the decades following the world wars, Canadians who were interned and had their property seized began lobbying for compensation for and recognition of their treatment. The Japanese Canadian redress movement led to an official apology from Prime Minister Brian Mulroney on the floor of the House of Commons in 1988. The terms of the settlement also included a redress (compensation) payment of $21,000 to each surviving individual affected by official policy; a community fund of $12 million; and funding for a Canadian Race Relations Foundation to support human rights projects.

Repeal of the War Measures Act

In 1988, the War Measures Act was repealed and replaced by the Emergencies Act. This created more limited and specific powers for the government to deal with security emergencies. Under the Emergencies Act, Cabinet orders and regulations must be reviewed and approved by Parliament. This means Cabinet cannot act on its own. The Act outlines how people affected by government actions during emergencies are to be compensated. It also notes that government actions are subject to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Canadian Bill of Rights.

The Emergencies Act also says that “Nothing in this Act shall be construed or applied so as to confer on the Governor in Council the power to make orders or regulations… providing for the detention, imprisonment or internment of Canadian citizens or permanent residents… on the basis of race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.”

See also Japanese Canadian Internment: Prisoners in their own Country; Interned in Canada: An Interview with Pat Adachi; Hide Hyodo Shimizu; Obasan (novel); Joy Kogawa; David Suzuki; Masumi Mitsui; Irene Uchida; Annie Buller.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom