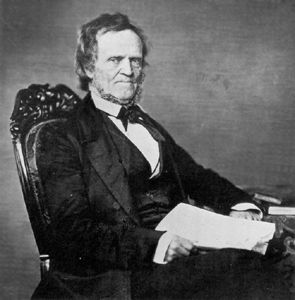

William Lyon Mackenzie, journalist, politician (born 12 March 1795 in Dundee, Scotland; died 28 August 1861 in Toronto, ON). A journalist, Member of the Legislative Assembly, first mayor of Toronto and a leader of the Rebellions of 1837, Mackenzie was a central figure in pre-Confederation political life. His grandson, William Lyon Mackenzie King, was Canada’s longest-serving prime minister.

Early Life and Career

Mackenzie was raised in Scotland as a secessionist Presbyterian by his widowed mother and ran a general store with her by 1814. After the business went bankrupt Mackenzie appears to have moved to find work, including some time in London, England, where he likely wrote for newspapers.

Mackenzie sailed to Canada in 1820 and soon settled in Upper Canada; after a few years in business at Dundas, he moved to Queenston. In May 1824 he published the first issue of the Colonial Advocate, which immediately became a leading voice of the new Reform movement. The Reform movement advocated responsible government and opposed the colonial regime that ruled Upper Canada at the time. As a radical Reformer, Mackenzie admired the American political system rather than the British model. To be closer to the provincial Parliament, Mackenzie moved his operation to York [Toronto] in the fall of 1824. His forthright and forceful manner together with his ardent denunciation of the Family Compact contributed to his popularity, and in 1828 he was easily elected to the House of Assembly for York County.

Political Career

Mackenzie's venomous attacks on the local oligarchy brought reprisals in the form of libel suits, threats and physical assaults, as well as an attack on his printing office in 1826, which left his press wrecked and the type thrown into the lake. Mackenzie’s scathing attacks on his opponents also led to his repeated expulsion from the Assembly, although he was continually re-elected by his rural constituents. In 1832 he visited England to present his political supporters' grievances before the imperial government. The sympathetic hearing he received outraged Upper Canadian conservatives. In 1834, when the Reformers won a majority on the newly created Toronto City Council, he was elected its first mayor. At the end of 1834, he was elected to the provincial Parliament again. However, he was defeated at the polls in 1836, and by late fall 1837 an embittered Mackenzie turned his mind to armed revolt.

Rebellions of 1837

On 5 December 1837, convinced that he would gain spontaneous support, he led an erratic expedition down Yonge Street towards Toronto. The rebels planned to march to the house of Lieutenant-Governor Sir Francis Bond Head and perhaps City Hall. However, the plan failed due to disorganized leadership and a lack of discipline. As the force neared Toronto it was dispersed by a few shots from loyalist guards. On 7 December, loyalist troops under Head marched north to Montgomery's Tavern and easily defeated the rebels. Mackenzie fled to the US and attempted to continue the rebellion from Navy Island in the Niagara River. He declared a provisional government and issued a proclamation calling for American-style democratic reform. Canadian militia bombarded the island and sank the rebel supply ship Caroline. Fellow rebels Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews were captured and executed for treason after pleading guilty to participating in the rebellion.

Exile

Mackenzie moved to New York where he founded Mackenzie's Gazette. However, he was convicted of violation of the US neutrality laws and imprisoned for a year, falling ill and deeper in debt. He spent the next 10 years in the US, eventually finding employment as a correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune. During exile he wrote several books, including The Sons of the Emerald Isle (1844), The Lives and Opinions of Benjamin Franklin Butler and Jesse Hoyt (1845) and The Life and Times of Martin Van Buren (1846).

Mackenzie returned to Canada in 1849 following a government pardon. Undaunted, he quickly resumed both his journalistic and his political careers, serving with characteristic energy as MLA for Haldimand until retirement in 1857 and occasionally publishing a political squib, usually entitled Mackenzie's Weekly Message. The fiery and principled Scot died at his home on Bond Street, now one of Toronto's historic sites and museums.

Did you know?

Mackenzie’s daughter Isabel Grace Mackenzie King was proud of her father and named her first son after him. William Lyon Mackenzie King would become Canada’s longest-serving prime minister, serving in that position in 1921–26, 1926–30 and 1935–48.

Controversy and Legacy

Mackenzie’s official biography was published by his son-in-law, Charles Lindsey, in 1862. More recently, his legacy has been fraught with controversy, and he has been hailed as both a political failure and a political hero. His critics describe him as an ineffectual mayor, unable to cope with Toronto’s debt or its divided council. Detractors cite his lack of coherent leadership as a fatal flaw.

Yet despite the failed rebellion of 1837, Mackenzie helped to define the necessary elements of a democratic society in a fledgling nation. In his 2002 biography of Mackenzie, former Toronto Mayor John Sewell argues that Mackenzie’s radical democratic ideals, including a fair election process, open public discussion of political issues, and the public’s involvement in the democratic process, remain relevant in the 21st century as they encourage greater public participation in politics. However, reports of Mackenzie’s eccentricities, such as his fiery temper, short stature and red wig, have at times detracted from his political legacy as a leader in the struggle for a responsible and responsive government in Upper Canada.

In Canadian literature, Mackenzie has appeared as a character in Dennis Lee’s poem 1838 and in Rick Salutin’s 1976 play entitled 1837: The Farmers’ Revolt produced by Theatre Passe Muraille in Toronto.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom