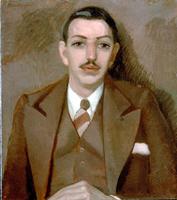

Paul-Émile Borduas, painter (b at St-Hilaire, Qué 1 Nov 1905; d at Paris, France 22 Feb 1960). Leader of the Automatistes and main author of the manifesto Refus Global, he had a profound influence on art in Québec.

In his youth he was fortunate enough to meet Ozias Leduc, who lived in the small rural district of Trente in Saint-Hilaire. Leduc took him on as an apprentice painter; bringing him to Sherbrooke, Halifax and Montréal (to the baptisteries of the Notre-Dame and the Saints-Anges à Lachine churches) and introducing him to the art of church decoration. Leduc encouraged young Borduas to study at the École des beaux-arts in Montréal (1923-27) and obtained from the then parish priest of Notre-Dame in Montréal, Monseigneur Olivier Maurault, the necessary funds to send him to France (1928-1930). He studied at the Ateliers d'art sacré in Paris, directed by Maurice Denis and Georges Desvallières.

This first contact with Europe was extremely important for the young Borduas; he discovered the painters of the Paris school, from Pascin to Renoir. Unlike his colleague Alfred Pellan, however, who spent 14 years in Paris, Borduas did not have any contact at this time with the Surrealists. Upon his return to Canada the economic crisis forced Borduas to abandon his dream of becoming a church decorator, a job for which he had been carefully trained and which had also been the occupation of his master, "Monsieur Leduc." To survive he had to fall back on the teaching of drawing in the primary schools of Montréal.

In 1937 Borduas obtained a post somewhat closer to his aspirations, that of professor at the École du Meuble. Throughout this period, he painted little and destroyed a large number of paintings. His style was still figurative and betrayed the influences of his Parisian masters, James W. Morrice and finally also Cézanne and Rouault. His discovery of the Surrealist movement and his reading of "Château étoilé" by André Breton (a text Borduas read in the review Minotaure and which eventually would become chapter 5 in Breton's L'Amour fou) were decisive for his further career.

In this chapter Breton cited Leonardo da Vinci's famous advice to his students to carefully look at an old wall until shapes and forms appear in its cracks and stains - shapes that the painter will only have to copy afterwards. This inspired Borduas to consider the piece of paper or the canvas on which he wanted to paint as a kind of psychic screen. By haphazardly tracing a few strokes, that is "automatically" and without any preconceived ideas, Borduas recreated Leonardo's "old wall." In this way he would only have to discover and refine arrangements in the drawing and, at a second stage, set them apart from the background by colour.

The art of pictorial automatism was born. Borduas's first automatist painting, if we are to believe him, was Abstraction verte in 1941. In 1942 he exhibited 45 "surrealist works" in gouache at the Théâtre de l'Ermitage in Montréal. This exhibition was a profound success. The year after, he attempted to transfer to oil the effects he had obtained in his gouaches, but not, however, without introducing important changes. To the dichotomy of drawing and colour which he had explored in the gouaches, he introduced the contrast of figure and ground. This technique is used, for instance, in Viol aux confins de la matière (1943).

It is possible to say that from then on the framework for his compositions became the landscape understood in its widest sense, incorporating interior visions that were closer to the dream and the unconscious than to any version of exterior reality. These new works were shown at the Dominion Gallery in Montréal in 1943 but were not greeted by collectors with the same enthusiasm that his gouaches had been received. In this period, too, Borduas's influence over his students at the École du Meuble as well as at the École des beaux-arts and the Collège Notre-Dame had begun to grow. He became the leader of the Automatistes movement and, together with his friends, exhibited in makeshift galleries from 1946 to 1947. These included Rue Amherst, at the house of Madame Gauvreau at 75 Sherbrooke Street West in Montréal and the small Galerie du Luxembourg in Paris. It was in one of these exhibitions that Borduas exhibited his painting Sous le vent de l'île in 1947. (The painting shows a continent rather than an island and fragmented pieces of objects that freely twirl around in the space over the land.)

The Automatistes movement culminated in the publication of the manifesto Refus global in 1948. In this manifesto, which was a collective effort but nonetheless mainly edited by Borduas, the authors denounced the old ideology of the preservation of past values - those values exemplified in the slogans "the past is our master" and "je me souviens "- and proclaimed the importance of opening up Québec society and culture to intellectual developments from around the world. Borduas's attacks against the Catholic church and the right-wing nationalism of Maurice Duplessis eventually cost him his teaching position. In 1949 he attempted to justify his actions in an autobiographical pamphlet entitled Projections libérantes, but this proved to be a wasted effort. He would never return to his position as teacher.

Borduas now had only the income derived from his painting to live on. The difficulties caused by his dismissal from the École du Meuble led him to separate from his family and to think about the possibility of leaving the country. He sold his house in Saint-Hilaire and made preparations to leave for New York. This was, however, still the period in which MacCarthyism reigned supreme in the US. Borduas had difficulty crossing the border because the authorities suspected him of having communist sympathies. It is true that he had interviewed Gilles Hénault for the communist review Combat, and although some of his followers such as Jean-Paul Mousseau sympathized with communism, Borduas himself never actually did. Moreover, in one of Refus global's paragraphs, entitled "Règlement final des comptes," Borduas distanced himself from the communist doctrine.

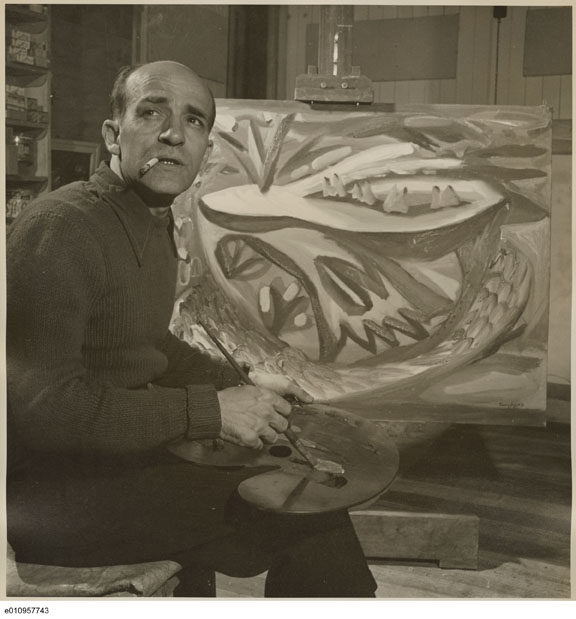

From 1953 to 1955, Borduas lived in New York, where conditions were less suffocating than in Québec. His painting took an enormous leap when he came into contact with the American abstract expressionist movement, attending their exhibitions and meeting their members - artists such as Franz Kline. Les signes s'envolent (1953) its title representative of the general feeling that drove him at the time, announced the elimination of the object from Borduas's paintings. Using only a spatula to apply his paint, he began to make his works increasingly textured.

While Borduas's first exhibition in New York took place at the Gisèle Passedoit Gallery, Martha Jackson would eventually become the sole representative of his work in the city. During this same period his student Jean Paul Riopelle was already exhibiting his paintings at the much more prestigious Pierre Matisse Gallery. Although American critics acknowledged that Borduas had been Riopelle's "teacher" and even went so far as to welcome him as the "Courbet of the 20th century," they generally remained more enthusiastic about Riopelle's painting. This contributed considerably to the estrangement between the two artists.

In the hope of receiving more recognition in France, Borduas left for Paris in 1955. His exile in Paris, however, proved to be particularly painful. Here, he did not find the success he had hoped for, and it was not until 1959 that he obtained his first solo exhibition at the Saint-Germain Gallery - four years after his arrival and one year before his death. Without the company of his friends (excepting Michel Camus, Marcelle Ferron and a small number of visitors from Canada such as the collectors Gisèle and Gérard Lortie), Borduas felt bored in Paris and his health declined.

His final compositions are all painted in contrasting black and white and only occasionally accompanied by a different colour. L'étoile noire from 1957, a work which is probably his masterpiece, is an example of this type of painting. Artistically closer to Piet Mondrian, Pierre Soulages or Franz Kline in Paris, Borduas cut himself off completely from the Surrealist movement; from the automatist technique he only retained the spontaneous manner in which he spread his paint on his support. His final canvases, essentially calligraphic works, reflected his desire for a new, though never realized, place of exile - this time Japan.

Although his paintings remained popular among Canadian collectors - art dealers such as Max Stern of the Dominion Gallery in Montréal and G. Blair Laing of its counterpart gallery in Toronto paid him regular visits and bought paintings from him - Borduas did not succeed in penetrating the European markets. Increasingly lonely, he dreamed of returning to Canada but died in Paris in 1960, leaving behind an outstanding body of art. Canadian museums such as the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Vancouver Art Gallery, the Musée d'Art Contemporain and the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal contain many examples of his work.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom