Pierre-Stanislas Bédard, newspaperman, judge, politician, Patriote (born 13 September 1762 in Charlesbourg, New France; died 26 April 1829 in Trois-Rivières, Lower Canada). A very timid and unimposing man, Pierre-Stanislas Bédard was one of Lower Canada’s most important political figures. A lawyer by training, Bédard was the leader of the very first political party in Canadian history: the Parti canadien. Under his leadership, this alliance of French Canadian deputies used the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada as a forum to promote greater authority for the Assembly in the colonial government.

Early Life and Career

Pierre-Stanislas Bédard was born at a complicated time in Canadian history. In 1760, following the French defeat at the Plains of Abraham and the subsequent arrival of the British fleet, Great Britain took possession of New France, just two years before his birth. In 1763, the colony was awarded to the British (see Treaty of Paris), and the status of the remaining French colonists remained uncertain. Despite the ambiguity of the first decades under British rule, Bédard enjoyed a relatively comfortable childhood. The Bédards, a middle-class family that arrived at Charlesbourg in the 1670s, enjoyed much influence around Québec City and were able to provide their children with an excellent education.

From 1777 to 1784, Pierre attended the Petit Séminaire de Québec, where he grew fond of philosophy and mathematics. After graduation, he studied law. In November 1790, he was called to the Bar. In July 1796, he married Luce-Louise Lajus, with whom he had five boys — the most famous of whom was his second-eldest son, Elzéar, who, in 1838, stirred up controversy when he declared Governor Colborne’s habeas corpus ordinance unconstitutional and refused to follow it (see Special Council of Lower Canada; Civil Liberties). According to historians Fernand Ouellet and Gilles Gallichan, Pierre-Stanislas Bédard was unhappy in his chosen profession. Not only disillusioned by the profession itself, he struggled financially as a lawyer.

Politics, Ideology and Le Canadien

Bédard found a happier home at the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada, where he was first elected in 1792 as the representative for Northumberland, a former electoral district in the vicinity of Québec City. He remained the representative of this riding until 1808, when he won a seat in the more prestigious district of Lower Town Québec. Bédard’s political career was on the rise. By 1805, Bédard became the leader of an emerging alliance of French Canadian deputies in the Legislative Assembly that would later be known as the Parti canadien. Influenced by the Age of Revolution, these highly educated and talented men had developed a political and national consciousness and wanted greater control over their colony (see French Canadian Nationalism).

Fairly timid and unimposing, Bédard made up for his shortcomings with his knowledge of British constitutional law. His beliefs became the backbone of the Parti canadien. Particularly, he maintained that the elected Legislative Assembly, and not the appointed Legislative and Executive councils, should run the colony. He championed a legislative assembly with greater control over the colony’s budget and argued that the members of the Legislative Council should be selected by the Legislative Assembly, not appointed by the governor general. Essentially, Bédard was asking for ministerial responsibility, a standard of the British parliamentary system stating that the government must remain accountable to the elected legislative assembly (see Representative Government). Bédard was not against British rule. He was a proponent of British institutions and understood the benefits of living under British rule. While colonists had little rights under French absolutism, under Britain’s constitutional monarchy, they enjoyed a constitution, an elected assembly and a political system based on a balance of powers. According to historian Fernand Ouellet, Bédard’s criticism of the political system in Lower Canada was that “the manner in which it has until now been administered imparts to it an effect quite contrary to this intention.”

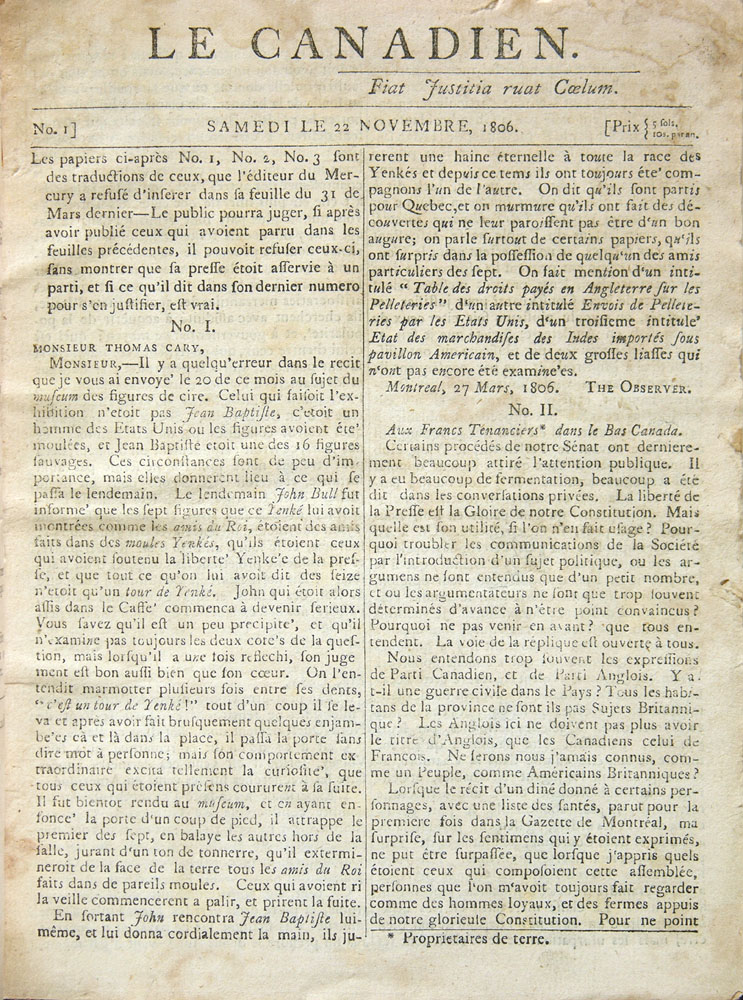

In 1806, Bédard founded a newspaper that became the voice of his party, Le Canadien. The paper was created in order to counter the Quebec Mercury, the voice of the British elite and a vocal opponent of the Parti canadien and French Canadians. Through the pages of Le Canadien, Bédard educated French Canadians on their constitutional rights, promoted the aims of the French Canadian majority in the Assembly, and fought for the preservation of the French Canadian “nation.” The newspaper was shut down by government officials in 1810. This was not the end of Le Canadien, however, as it later became the colony’s most influential newspaper when, in 1822, Étienne Parent took over editorial duties.

Parti canadien

Under Bédard’s guidance, the Parti canadien dominated the Legislative Assembly. According to historian Gilles Laporte, it became the very first political party in Canadian history. However, as a result of the 1791 Constitutional Act, its actual political power was limited; the governor and his appointed councils remained the true source of colonial authority. As such, the Legislative Assembly did not did not have the authority to alter the colony’s laws and constitutions. Unable to reform the colony to fit his vision, Bédard (and his party) used the Assembly as a forum to pressure the government for change.The party especially opposed the power of the English-speaking minority over the colony, a group known as the Château Clique. Though this group included some French Canadians, it was mostly an alliance of British merchants from Montréal and Québec City who used their influence in the governor’s appointed Legislative and Executive Councils to promote an agenda beneficial to their political and business aims.

By 1808, Bédard’s party dominated the Assembly and its deputies were consistently re-elected. Frustrated with the party’s demands, Governor General James Henry Craig (1807‒11) — whose tenure was described by some as a “reign of terror” for French Canadians — went on the offensive. He dissolved the Assembly in 1809 and 1810, calling elections with inconsequential results: Parti canadiendeputies returned in large numbers. In 1810, he arrested and imprisoned Bédard and other staff members from Le Canadien, including François Blanchet, Jean-Thomas Taschereau (see Taschereau Legal Dynasty) and Charles Lefrançois, for traitorous activities. One after another, Blanchet, Taschereau and Lefrançois gave in and signed letters apologizing for their actions and paid a fine. Bédard refused and spent 391 days in prison demanding a fair trial. Claiming that the danger that Bédard represented had passed and that his imprisonment was simply precautionary, Craig released him in April 1811. Craig, who was ill, returned to England shortly thereafter.

Post-Parti Canadien life

Out of prison, Bédard struggled financially. In order to make up for his imprisonment, the new governor, George Prévost, offered him a post as judge on the Court of King’s Bench at Trois-Rivières. With a salary of £600 per year, Bédard accepted and took up his new post in 1813. This position was given to him for another reason: Prévost wanted to keep men who were considered extremists or dangers out of politics. By giving him a job as a judge and moving him from Québec City to Trois-Rivières, he did just that.

Bédard was unhappy with his new position and even wrote in 1814 that he would trade the money and the comfort of it for the happiness he experienced while he was at the Legislative Assembly. He remained a judge until his death in 1829.

Despite an unhappy end to his life, Bédard is one of the most important political figures in Canadian history. The political party he helped create is not only recognized as the first in Canada, but it continued to fight for French Canadian interests for years to come as the Parti patriote.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom