Canada is home to 10 species of pine trees. Distinguishable by their bundles of two, three or five needles, various species can be found throughout Canada’s provinces and the Yukon and Northwest Territories. These conifers can live for hundreds of years, with the oldest pine tree in the world being around 4,900 years old and located in Nevada. Two pine species are designated provincial trees in Canada: the lodgepole pine in Alberta and the eastern white pine in Ontario.

Canada’s Pine Species

|

Species |

Description |

Habitat and Range |

|

Pinus strobus Eastern white pine |

Eastern white pines have five-needle bundles and are fast growing, reaching up to 30 m in height. They have a straight, slender trunk and their branches give the tree an oval-like silhouette. They can live up to 200 years. |

This species grows best on moist, sandy terrain and thrives in full sunlight. Distributed across the eastern regions of Canada, particularly southern Ontario and Quebec, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland and Labrador. They are also found in the northeastern regions of the United States. |

|

Pinus banksiana Jack pine |

Jack pines have needle bundles of two, grow up to 20 m in height and can live up to 150 years. Their crown is short and their trunk is narrow and slightly tapered. Their seeds, varying in shape and held closed by a resin bond, only open when exposed to extreme heat from wildfires or heat waves. |

Usually found in sandy or rocky soils, this species is often the first to occupy damaged terrain due to wildfire. Jack pines are Canada's most widely distributed pine, largely coinciding with the Canadian Shield. |

|

Pinus flexilis Limber pine |

Limber pines are smaller, typically reaching a maximum of 12–15 m in height, and can live for several hundred years. This tree gets its name from its flexible, “limber” branches that slowly droop with age. |

This species’ habitat consists of rocky, exposed terrain but can grow in a variety of soils. In Canada, they are only found in a small section of southern British Columbia and Alberta. |

|

Pinus contorta Lodgepole pine |

With two-needle-bundles, the lodgepole pine can reach heights of 30 m and can live up to 200 years old. This tree has a long, slender trunk with short branches appearing about halfway up. Their seeds, held closed by a resin bond, only open when exposed to extreme heat from wildfire or heat waves. |

Lodgepole pines are found in a variety of habitats and soils, from rocky terrain to water-logged bogs. They are found in the Yukon, British Columbia and Alberta. They are found sparsely in Saskatchewan and dip into the northwest United States. |

|

Pinus rigida Pitch pine |

Growing yellowish-green three-needle bundles, the pitch pine can grow up to 20 m in height and live for 200 years. Their cones can open due to maturity, extreme heat or at irregular intervals, and can stay on the tree for many years. |

Pitch pines grow in harsh environments such as dry sand plains, gravelly slopes, rocky ridges and swamps. In Canada, they are primarily found in a small area along the St. Lawrence River in eastern Ontario. |

|

Pinus ponderosa Ponderosa pine |

As one of the tallest pines found in Canada, the ponderosa pine typically grows up to 35 m tall and can live up to 600 years old. Their needles, which usually come in groups of three, are very sharp and stiff. The bark of this pine smells like vanilla or butterscotch. |

Ponderosa pines are typically found in mountainous or rocky habitats. They are found dotted across the western United States and in southern British Columbia. |

|

Pinus resinosa Ait. Red pine |

The red pine has brittle and pointed needles in bundles of two. They can grow up to 35 m and live for 200 years. The tree gets its name from its reddish bark, which forms a scaly pattern as it ages. |

This tree is found in sand plains, rock outcrops, and sites with low soil fertility. It is distributed throughout eastern Canada, from southeastern Manitoba to Newfoundland. |

|

Pinus contorta Shore pine |

The shore pine’s sharp, dark green needles come in bundles of two. With an often-crooked trunk and deformed crown, this tree typically grows up to 15 m tall. |

Following its name, the shore pine is typically found along coastal sand dunes and rocky terrain. In Canada, this tree is only found in coastal British Columbia and grows below 600 m of elevation. |

|

Pinus monticola Western white pine |

The western white pine has soft, evergreen five-bundle needles. With age, the tree’s bark transforms from a smooth layer to a hexagonal, scaly bark, gradually getting darker each year. One of the largest and longest-living pines in Canada, the western white pine can grow up to 50 m and can live for 400 years. The crown begins about halfway up the tree and remains slender with little taper. |

This is the only five-needled pine that grows at low elevations in western Canada, but can also be found at higher elevations near the coast. It is found on a wide variety of terrain, from bogs to sandy shores to rocky earth. In Canada, it is found mainly in southern British Columbia, and travels down to Montana, Washington, Oregon, Idaho and northern California. |

|

Pinus albicaulis Engelm. Whitebark pine |

The whitebark pine has yellow-green, five-bundled needles that remain on the tree for four to eight years. The bark is chalky-white when young, but grows to a darker brown with age. This tree grows up to 30 m tall and can live for 500 years. |

This tree typically grows at higher elevations — from 1,000 m to the treeline. The higher the elevation, the more the tree resembles a large shrub. In lower elevations, it grows more upright. It requires a moist climate and can be found along rocky terrain in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia and Alberta. |

Wildlife

Conifers, with their nutrient-dense seeds, bark and needles, are vital food sources for multiple animals. Squirrels and various birds find seeds in dropped pine cones, while larger wildlife like bears and deer feed on bark and needles. Pine trees offer year-round relief for nourishment and shelter, especially throughout winter, when food sources are hard to come by.

Indigenous Peoples

Various Indigenous communities are familiar with the pine’s many uses, from valuable food sources to medicinal needs to building materials. As is common practice within many Indigenous communities, every part of the tree, from roots to leaves, often has a specific use.

Uses vary between species. The trunks of ponderosa pines were often hollowed out to make canoes, while the trunks of lodgepole pines were used as structural supports for buildings and tipis. Many of the pines were good for making medicinal tea and remedies. The lodgepole pine, for example, had many healing uses. The resin was used to help sore throats, toothaches and infections, while the inner bark was used as bandages.

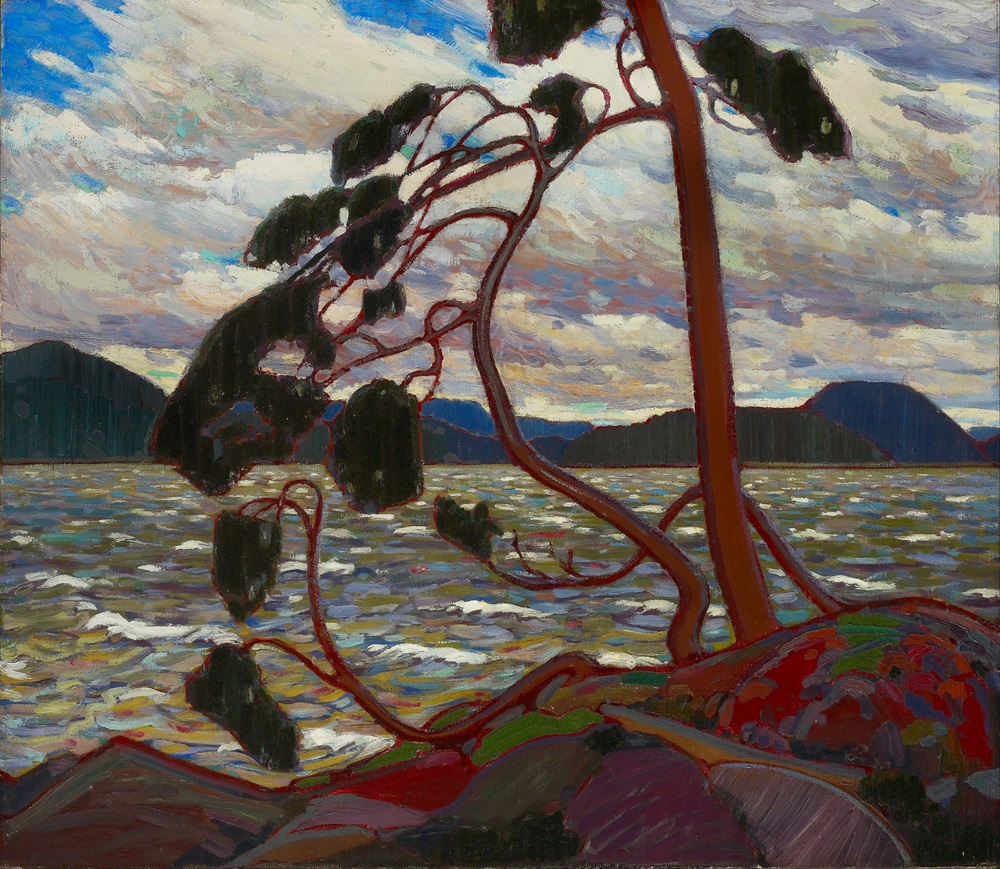

The eastern white pine is of special significance to many Indigenous peoples. As the provincial tree of Ontario and a species that has appeared in Haudenosaunee history and stories for centuries, this tree represents the Great Tree of Peace — a symbol of unity and strength — in both Canada and the United States.

Uses

Currently, pine trees are mainly harvested for building materials. The wood is largely used to make siding, trim, panelling, plywood, furniture and many other materials. Other uses include railway ties, wood pulp and structural supports.

Threats

Both the limber pine and whitebark pine are classified as endangered by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). The primary threats to these species are white pine blister rust, fire suppression, mountain pine beetles and climate change.

White pine blister rust appears as an orange, blister-like fungus growing along the bark of the pines, attacking the tree from the inside. This non-native fungus was brought over from Europe in the early 1900s. Less than 1 per cent of whitebark and limber pine are naturally rust resistant.

The mountain pine beetle has been a present threat to multiple pine species throughout North America since the 1990s, but affects the lodgepole pine most significantly. As the beetle has migrated far past its historic range due to consistently warmer and dryer weather, it has attacked 50 per cent of British Columbia’s commercial lodgepole pines since the 1990s.

Modern fire suppression management has restricted natural wildfires’ ability to rejuvenate the forest, creating a dense, shady habitat. This results in poor growth outcomes for many pine species and perfect conditions for large, out-of-control fires.

See also Four Major Insect Pests of Forests in Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom