Creation

Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson established the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada in 1967 in response to a months-long campaign by a coalition of 32 women’s groups led by Ontario activist Laura Sabia, then president of the Canadian Federation of University Women. In May of the previous year, Sabia had called a meeting of the coalition in Toronto to discuss concerns surrounding the status of women in Canada. It was the coalition’s campaign, mounting pressure from the media and Sabia’s threat of a march two million women strong on Parliament Hill that prompted the Prime Minister to set up the commission. Judy LaMarsh, the only woman in the Cabinet and secretary of state from 1965 to 1968, also played an important role in its creation.

The commission’s mandate was to inquire into and report on the status of women in Canada, and to make specific recommendations to the federal government to ensure equality for women in all aspects of society. The commission was launched at a time when the women's movement was in full swing and other governments worldwide were addressing similar issues.

Hearings and Report

This was to be the first royal commission of inquiry chaired by a woman: Florence Bird, an Ottawa journalist and broadcaster. Bird was joined on the commission by two men and four women: Jacques Henripin, a professor of demography at the Université de Montréal; John Humphrey, the McGill University law professor who had drafted the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights; Lola Lange, a farmer and community activist from Claresholm, Alberta who did advocacy work for Indigenous women; Jeanne Lapointe, a professor of literature at Université Laval who had been a member of the Royal Commission of Inquiry on Education in the Province of Québec; Elsie Gregory MacGill, an aeronautical engineer from Toronto, and Doris Ogilvie, a juvenile court judge from Fredericton, New Brunswick. The commission’s executive secretary was Monique Bégin, a young sociologist who had worked closely on women’s issues with Thérèse Casgrain and who would go on to become the first woman from Québec to be elected to the House of Commons.

The inquiry began in the spring of 1968. Public hearings were held across the country over a period of more than six months. The commission attracted considerable interest, reviewing 468 briefs and receiving over 1,000 letters of opinion and additional testimony, all of which confirmed the widespread problems faced by women in Canadian society.

The commission’s 488-page report contained 167 recommendations to the federal government on such issues as pay equity, the establishment of a maternity leave program and national child care policy, birth control and abortion rights, family law reform, education and women’s access to managerial positions, part-time work and alimony. A large section also addressed issues specific to Aboriginal women and the Indian Act. All of these recommendations were based on the core principle that equality between men and women in Canada was possible, desirable and ethically necessary.

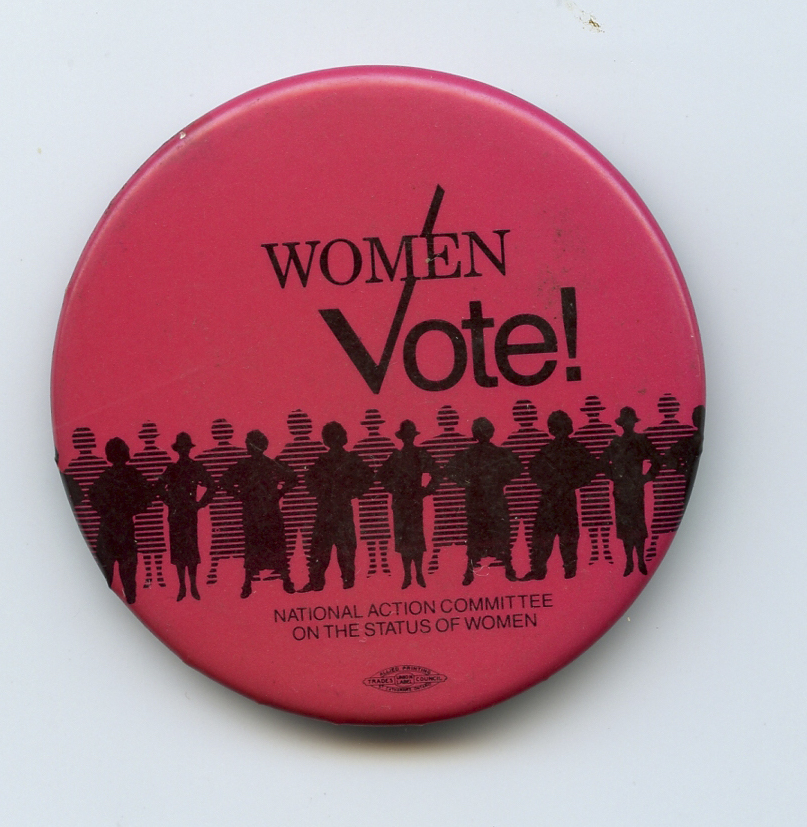

Tabled in the House of Commons on 7 December 1970, the landmark Report of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada defined the status of women as a social problem to be addressed collectively rather than individually. It highlighted the obstacles faced by women and recommended changes to eliminate gender inequality by means of social policy, serving to mobilize women’s groups around common causes. The largest conglomeration of feminist organizations in Canada, the National Action Committee on the Status of Women, was formed with the aim of lobbying the government to implement the recommendations in the report.

Reception and Implementation of the Recommendations

In response to one of the recommendations, the federal government established the Office of the Co-ordinator, Status of Women (Status of Women Canada) in 1971 and created the position of Minister responsible for the Status of Women. The government agency was initially overseen by the Privy Council Office, but became an independent agency in 1976. It is funded by an annual budget approved by Parliament and its coordinator, an order-in-council appointment, is its head of agency. Around the same time, the government established the Canadian Advisory Council on the Status of Women in 1973. Until it was dismantled in 1995, this independent agency’s mandate was to advise the government and inform the Canadian public about women’s issues.

By the 1980s, most of the report’s 167 recommendations had been either partially or fully implemented. The commission, however, had numerous detractors, who notably criticized the report’s failure to address widespread issues such as the alleviation of poverty, which disproportionately affects single mothers and their children.

Another widespread social problem that was virtually ignored in the commission’s report was violence against women, but by the 1980s, public awareness of the issue was growing, especially in the aftermath of the attack at Montréal's École Polytechnique, during which 14 young women were murdered by antifeminist Marc Lépine (see Antifeminism in Québec). This historic tragedy became a defining moment for awareness-raising around the issue of violence against women. Since 1991, 6 December has been the National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women (see also The École Polytechnique Tragedy: Beyond the Duty of Remembrance).

Policy-makers have only recently begun to examine some of the issues the commission did not raise at the time, such as those affecting the gay and transgender communities (see Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights in Canada).

Legacy

Despite its failings, the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada was undeniably a catalyst for social change. It united Canadian women to a greater extent than ever before and gave them a voice in shaping gender-responsive policies. In addition to shining a spotlight on women’s rights, it led to important social victories, including an equal minimum wage and maternity leave.

As early as 1973, the provinces and territories, with the exception of British Colombia, began establishing advisory bodies based on the federal government’s model, the Canadian Advisory Council on the Status of Women. Many still exist today despite being seriously affected by major budget cuts in recent years (see, in particular, Council on the Status of Women). Others, like the New Brunswick Advisory Council on the Status of Women, have simply been shut down.

Every Canadian province now has a minister responsible for the status of women. At the federal level, Status of Women Canada now focuses its efforts on advancing equality for women and girls by working with provincial and federal programs to increase women’s economic security, encourage women’s leadership and democratic participation, and end gender-based violence.

See also Women and the Law; Women's Suffrage.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom