Family Background

James Douglas was the son of John Douglas, a Scottish merchant of cotton and sugar who owned a plantation in Demerara, a Dutch colony in present-day Guyana. The Douglas family was well-established in Scotland, and John was descended from the earls of Angus. John’s brother, Lieutenant-General Sir Neil Douglas, became Commander-in-Chief for Scotland in 1842.

James Douglas’s mother was Martha Ann Ritchie, a free woman of colour who had been born in Barbados. The term coloured generally referred to a person of mixed race who was of African and European ancestry. The description that she was free indicates that she was not enslaved (see also Black Enslavement in Canada).

Martha Ann was the daughter of a free woman of colour, Rebecca. In the 1790s, mother and daughter moved to what is now Guyana in search of better economic opportunities. Rebecca eventually became a hotelier and boarding-house keeper outside of Georgetown and owned 30 slaves. Martha Ann met John Douglas while he was on plantation business. They had three children together, though they never married. John Douglas returned to Scotland, where he married in 1809 and started a second family.

Education

In 1812, when James Douglas was nine years old, his father sent him and his brother, Alexander, to Lanark, Scotland, for schooling. James never returned to Demerara or saw his mother again.

With the North West Company

In 1819, when he was 15, Douglas was apprenticed to the North West Company (NWC), a major force in the fur trade, and sailed to Montreal. He spent his first years working in the counting houses of Fort William (in present-day Ontario) and Île-à-la-Crosse (Saskatchewan), learning the fur trade and its accounting practices.

At the time, intense competition between the NWC and the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) escalated from economic conflict to occasional physical violence (see Battle of Seven Oaks). The teenaged Douglas was soon drawn into the fray. In late 1820, he fought a bloodless duel with Patrick Cunningham, an HBC guide. In April 1821, Douglas was one of four Nor’Westers the HBC warned not to parade within gunshot of Fort Superior with “Guns, Swords, Flags, Drums, Fifes, etc., etc.” Months later, Douglas became an employee of the HBC after it merged with the NWC.

With the Hudson’s Bay Company

In 1826, Douglas was posted at Fort St. James in the New Caledonia district (now mainland British Columbia). He was asked by Chief Factor William Connolly to join the first overland fur brigade from Fort Alexandria on the upper Fraser River to Fort Vancouver (now Vancouver, Washington) on the Columbia River. According to Connolly, Douglas was a “Fine steady active fellow good clerk & Trader, well adapted for a new country.”

On 27 April 1828, Douglas married Connolly’s daughter, Amelia, whose mother, Miyo Nipiy, was Cree. (The couple was also married in a Anglican ceremony at Fort Vancouver in 1837.)

George Simpson, governor of Rupert’s Land, met Douglas at Fort St. James in 1828. He described Douglas as “a stout, powerful active man of good conduct and respectable abilities.” However, Simpson also mentioned that Douglas became “furiously violent when aroused,” a tendency that brought him into conflicts with the Dakelh (Carrier) peoples. In 1830, Connolly recommended that Douglas be transferred to Fort Vancouver due to his weakened relationship with the Dakelh.

At Fort Vancouver, Douglas served under Chief Factor John McLoughlin, who was superintendent of the Columbia District of the fur trade for two decades. Douglas was later promoted to chief trader (1835) and chief factor (1839).

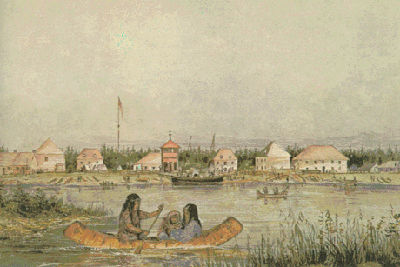

In 1840, Douglas travelled to Alaska to negotiate boundary and trade deals with the Russian American Company. In 1843, as American influence in the Pacific Northwest increased, Douglas began constructing Fort Victoria on the southern tip of Vancouver Island to replace the northern coastal forts.

In 1846, the Oregon Treaty established the forty-ninth parallel as the border between the United States and British North America in the West, leading the HBC to withdraw from Fort Vancouver. That same year, Douglas established a new fur brigade on British territory, from New Caledonia to Fort Langley on the lower Fraser River. Fort Victoria, where the furs from the interior were shipped, became the HBC’s main Pacific depot in 1849.

Governor of Vancouver Island

In order to prevent American expansion northward, Vancouver Island was declared a Crown colony on 13 January 1849 and was leased to the HBC for 10 years. Douglas, the supervisor of the fur trade since 1845, was appointed HBC agent on the island. However, the British government selected barrister Richard Blanshard for governor.

Blanshard arrived at Fort Victoria in March 1850 to find his residence incomplete. He soon learned that the HBC had virtual control of the colony’s affairs, that most British colonists were associated in some way with the company and that power ultimately rested with Douglas, the chief factor. Blanchard resigned and departed Vancouver Island in August 1851.

On 30 October 1851, Douglas learned he had been chosen as governor. His worries were great. He was often criticized for a conflict of interest between his duties as governor and as HBC chief factor, and for the appointments he made to key positions in the colony. According to Douglas, qualified men were in such short supply that he appointed his own brother-in-law, newly arrived from Demerara, as chief justice of the Supreme Court.

In 1856, Douglas was instructed by the Colonial Office to establish an elected legislative assembly for the island (see Responsible Government). He was opposed to universal suffrage and believed that people really wanted “the ruling classes” to make their decisions. Because of this, Douglas set property qualifications for the right to vote and for membership in the assembly that were so high only a few landowners qualified.

Douglas Treaties

From 1850 to 1854, Douglas negotiated 14 land purchases with First Nations on Vancouver Island, including land in and around Fort Victoria, Fort Rupert and Nanaimo. These are known as the Douglas Treaties or Fort Victoria Treaties (see Treaties with Indigenous Peoples in Canada). In each, lands were purchased in exchange for small amounts of cash, clothing, blankets, occupation of reserved lands, and hunting and fishing rights on unoccupied ceded lands.

These treaties have long been disputed for several reasons, including the fact that the terms of the agreements were left blank at the time of signing, with the clauses inserted at a later date. According to Indigenous oral history, many of the signatories assumed they were signing a peace treaty to share, not cede, their lands. They reportedly thought that the X they were asked to sign was the symbol of the Christian cross, which they perceived as a spiritual gesture. Others assumed the agreements were a confirmation of their agricultural lands and village sites.

![“Ho! For Frazer River” [sic] “Ho! For Frazer River” [sic]](https://d3d0lqu00lnqvz.cloudfront.net/media/new_article_images/FraserRiverGoldRush/512px-Peep_at_Washoe_-_Ho%21_For_Frazer_River.jpg)

Illustration by J. Ross Browne from "A Peep at Washoe" in Harper's Monthly Magazine, December 1860.

Fraser River Gold Rush

On 25 April 1858, a boatload of boisterous miners from California — the first wave of 25,000 newcomers — arrived in Fort Victoria on their way to search for gold on the Fraser River sandbars (see Fraser River Gold Rush). To that point, Vancouver Island and mainland New Caledonia were sparsely populated by European settlers. About 500 settlers lived on Vancouver Island and about 150 on the mainland.

Concerned by the arrival of so many Americans, Douglas wrote to London: “If the majority of immigrants be American, there will always be a hankering in their minds after annexation to the United States.… They will never cordially submit to English rule, nor possess the loyal feelings of British subjects.” (See also Manifest Destiny.) Douglas understood that British authority over the Fraser River region was too limited to enforce any kind of law and order. As he wrote to British Prime Minister Edward Stanley on 19 May 1858: “I am now convinced that it is utterly impossible, through any means within our power, to close the gold districts against the entrance of foreigners, as long as gold is found in abundance, in which case the country will soon be over-run.”

Douglas took the precaution of claiming the land and the minerals for the Crown. He also distributed licenses to the miners and, to stem an invasion, stopped foreign vessels from entering the river. For this action, which seemed designed to protect the HBC monopoly, he was reprimanded by the Colonial Office.

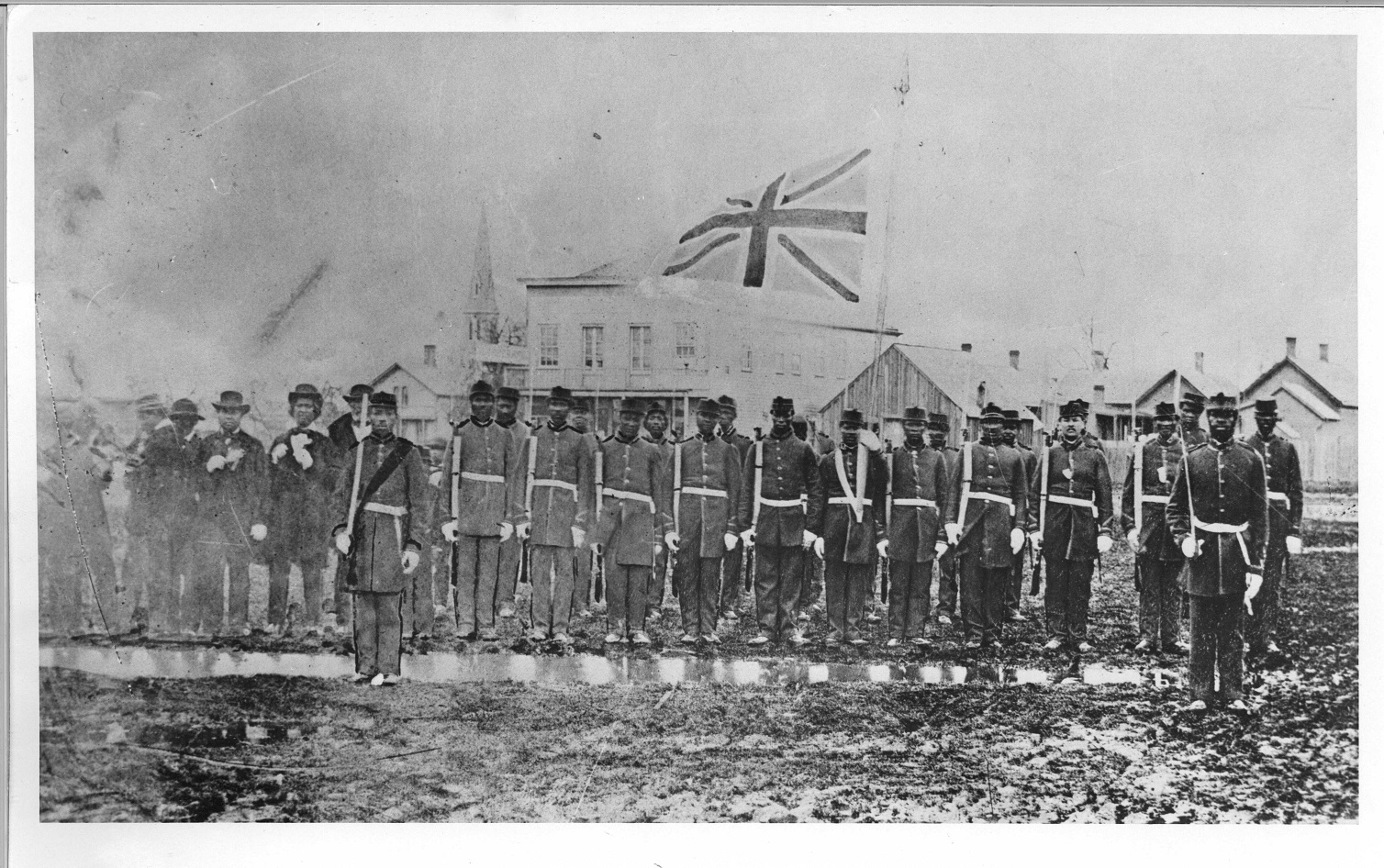

In search of immigrants who might be sympathetic to Britain, Douglas reached out to members of San Francisco’s Black community, who had been discussing the need to emigrate to a more welcoming environment. In 1857, a United States Supreme Court decision had denied citizenship to both free and enslaved African Americans. Douglas promised them British citizenship after five years of land ownership and full protection of the law in the meantime. The community established a 35-member “pioneer committee” to investigate the offer, meeting a “very cheerful and agreeable” Douglas in Victoria on 25 April 1858. Not long after, several hundred Black families moved to the colony ( see Black History in Canada).

Did you know?

In 1860, Governor James Douglas approved the creation of the Victoria Pioneer Rifle Corps, a Black volunteer militia unit. The Pioneer Rifles, which quickly recruited 60 men, is considered the first British or Canadian military unit formed west of Ontario. The unit had dissolved by 1866, however, after Douglas’s successor as governor, Arthur Edward Kennedy, withdrew government approval. (See also Black Soldiers in 19th Century Canada.)

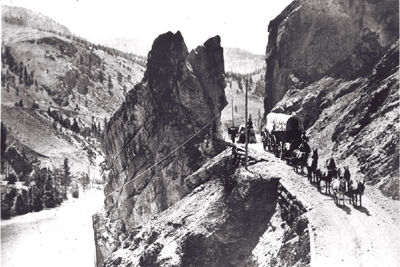

The Fraser Canyon of British Columbia is the traditional territory of the Nlaka’pamux people.

Fraser Canyon War

Douglas also believed that the American miners would provoke a bloody military conflict with the Nlaka’pamux peoples and surrounding Indigenous communities along the Fraser River. He expressed these concerns in a letter to his superiors in England on 15 June 1858, saying: “It will require I fear the nicest tact to avoid a disastrous Indian war.” However, the British could not respond fast enough to restrict the miners’ entrance into the country. By June 1858, thousands of miners from the United States had already made their way to the lower reaches of the Fraser River.

As the summer wore on, miners disrupted Nlaka’pamux communities. Some of the men committed acts of sexual violence against Nlaka’pamux women, mined gold without consulting Nlaka’pamux community leaders for permission, threatened violence when challenged and disrupted the Nlaka’pamux salmon fishery. Faced with this sudden mass invasion of foreigners, some members of the Nlaka’pamux nation took up arms to defend themselves.

Douglas tried to maintain order in the area. He ordered a gunboat to patrol the mouth of the Fraser River and to demand licenses from miners trying to make their way to the goldfields. Still, Douglas had little to no military capability to assert Crown sovereignty over the mainland. In response to the escalating violence and at Douglas’s request, Britain made a proclamation on 2 August, laying claim to the Fraser River area as part of the Crown Colony of British Columbia.

On 9 August 1858, an already tense situation between miners and the Nlaka’pamux people erupted into war. Departing at Fort Yale, miners marched upriver and fought the Nlaka’pamux. It is unclear exactly how many Nlaka’pamux non-combatants were killed by the miners. Between 9 and 17 August, they killed upwards of 36 people, five of whom were chiefs. They wounded many others and took three prisoners. Retreating downriver, the company burned five Nlaka’pamux villages to the ground. According to one observer, the miners “just killed everything, men, women and children.” (See also Fraser Canyon War.)

On 22 August, a truce was brokered between the miners and the Nlaka’pamux. In late August, Douglas travelled to the Fraser Canyon, accompanied by 35 armed men, “in hopes that early measures will be taken by Her Majesty’s Government, to relieve the country from its present perilous state.” However, the war was largely over by this point.

Governor of British Columbia

With the gold discovery, Britain decided to cancel the special privileges that had been granted the HBC until March 1859. Douglas was offered the governorship of the new colony of British Columbia, this time on the condition that he sever his fur-trade connections. He would be given extensive political power, since it seemed unwise to experiment with self-government among men “so wild, so miscellaneous, and perhaps so transitory.” In November 1858, Douglas, who was still governor of Vancouver Island, was inaugurated at Fort Langley as governor of British Columbia. He was also appointed Companion of the Order of the Bath, in recognition of his administration of Vancouver Island.

Douglas expected that a location near Fort Langley would be chosen for the colony’s capital. But for military reasons, Colonel Richard Clement Moody in January 1859 selected a steep, heavily timbered site (New Westminster) on the north bank of the Fraser River. Douglas was concerned about the cost involved in laying it out. He also preferred Victoria as an administrative centre and as his place of residence. His visits to New Westminster were rare, and despite the grant of municipal self-government in 1860, the citizens of British Columbia demanded a resident governor and political reform.

As governor of British Columbia, Douglas was chiefly concerned with the welfare of miners. He relied on his gold commissioners to lay out reserves for Indigenous peoples (thus eliminating the threat of warfare), to record mining and land claims and to adjudicate mining disputes. For the gold colony, he devised a land policy that included mineral rights.

By 1862, Douglas was planning to finance by loans (about which London was not fully informed) a wagon road 640 km long following the Fraser River to distant Cariboo, where gold nuggets had been found (see Cariboo Road). It was extended in 1865 to Barkerville, a booming mining community (see Cariboo Gold Rush).

Retirement in 1864

Beginning in 1860, the citizens of British Columbia made several petitions to Douglas for a form of popular government in the colony. Dissatisfied with his response, they directly petitioned the Colonial Office in London in 1863. It seemed an opportune time to retire Douglas as governor of both Vancouver Island and British Columbia, and he left the following year. Douglas was praised for his work and talents and invested as a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath, which earned him the title Sir. Douglas toured Europe in retirement before returning to Victoria, where he died of a heart attack on 2 August 1877.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom