History

Structures built using very similar materials and techniques as sod houses appear in many cultures across the globe and long predate European settlement of North America. Humans have used the earth for shelter for much of their history, and the sod house in Canada was the product of centuries of precedent. Indigenous peoples in southern British Columbia, the Prairies, the Arctic and Labrador commonly built housing with sod (see Architectural History: Indigenous Peoples).

The Siglit Inuvialuit, for example, built structures with driftwood, using thick layers of sod cut from tundra grass for insulation. Called igluryuaq, these buildings often had tunnel entrances and a central gathering space where inhabitants could share heat. They were considered cold season dwellings, along with napaqtaq and kadjigi (also built with driftwood and sod) and iglu (built with snow).

On the northern tip of Newfoundland, the archaeological site L’Anse aux Meadows contains a number of sod structures, thought to be built by Norse settlers about the year 1000.

Homesteading

In 1870, the Canadian government granted provincial status to Manitoba, and the following year entered into Treaty 1 with the Anishinabek and Cree of southeastern Manitoba, and Treaty 2 with the Anishinabek of southwestern Manitoba. For the Canadian government, the treaties were intended to facilitate both Euro-Canadian settlement of the West, along with the assimilation of Indigenous peoples (see History of Settlement in the Canadian Prairies).

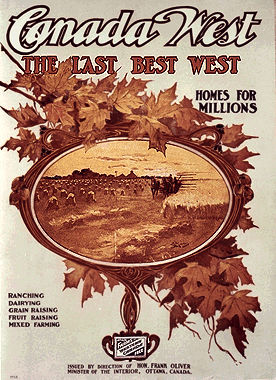

In 1872, the Dominion Lands Act established a means of distributing lands in the West to settlers. In exchange for a $10 fee and their agreement to establish a habitable residence on the land within three years, potential settlers received 65 hectares. The program was heavily advertised by the Canadian government, seeking to people the “Last Best West.” The Act was modeled on the American Homestead Act of 1862.

Since heavily wooded areas on the Prairies were scarce, and settlers lacked the infrastructure to build their traditional style of home, they explored alternative construction methods. Western expansion in Canada was largely fuelled by immigration, especially from Eastern Europe. Some brought knowledge of sod construction from their home countries. (See also Homesteading.)

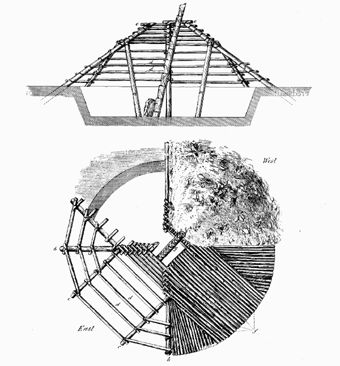

Construction

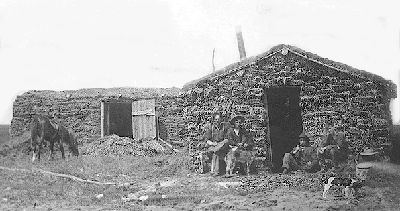

Sod houses were cheaply built out of available sod, which refers to grass and the soil beneath that is held together by the grass’ roots. If the settler accrued any costs in construction, it was for such comforts as windows, hinges and boards for a door. Blocks of sod were extracted first by ploughing long, 30–40 cm wide furrows in dry sloughs. Sod, some 10 cm deep, was cut into 60–80 cm lengths. Sod blocks were held together by overlapping, and by their long, fibrous grass roots. Placed grass-side down, these blocks of sod were used as bricks that produced thick, tight walls. For the roof, boards or light poplar poles were usually covered with sod, but sometimes they might be covered with hay or straw thatch. Techniques varied, depending on materials available or local peculiarities.

The average house was around 432 square feet (about 40 m2), the minimum size required under homesteading law (see Dominion Lands Act). The interior walls might be covered by paper or cloth, or plastered with a clay mixture and whitewashed. Houses were often partitioned into rooms using blankets or cowhides. Unfortunately, sod roofs leaked, with one day’s rain outside resulting in two days’ worth of runoff inside. Whitewashing somewhat alleviated the damp conditions inside. Despite their basic form, sod houses were cool in the summer and warm in the winter. Sod houses were intended to provide a temporary shelter while settlers established a more substantial residence.

Significance and Legacy

The archaeological evidence provided by sod houses has shed light on the movement and settlement patterns of the early inhabitants of North America. Archaeological excavations in the Atlantic provinces have revealed the existence of late 16th-century Inuit settlements in southern Labrador. The site at L’Anse aux Meadows is generally accepted to be proof that Europeans had landed in North America about the year 1000.

Despite log cabins and shacks being more commonly used than sod houses in the settlement of the West, sod houses have come to epitomize a romantic vision of hardship and survival during on the Prairies (see Ukrainians: Homesteading in the Parkland).

A famous and substantial example of Canadian sod houses is the Addison Sod House in Kindersley, Saskatchewan, built between 1909 and 1911. Although most sod houses were temporary structures that eventually degraded, the Addison Sod House was built with a wooden roof and ingenious variants on established sod construction methods, which has helped it survive to the present. Among other techniques, the walls were built to slope inward, creating a strong structure from about four feet thick at the bottom of the walls to three feet at the top. The structure was designated a National Historic Site by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board in 2004 (see Historic Site).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom