Sports Facilities

Sports facilities in Canada - including arenas, stadiums and curling rinks, swimming pools and specialized Olympic installations - are among the country's most important cultural buildings. It could be argued that the rules of sport, common from St John's to Victoria and acknowledged by all who choose to enter these places of exercise and entertainment, have more strongly united Canadians than either language, politics or national heritage. As the largest enclosed gathering spaces in Canada, arenas are capable of bringing together as many as 21 000 people while stadiums can assemble some 65 000. Through their historic and continuing role in hosting STANLEY CUPs and GREY CUP games, World Series and pop music concerts, these buildings have served as the sites for many Canadians' most cherished memories, repositories of hopes, dreams and triumphs.

Arenas and stadiums have even been accorded the status of secular shrines in the hearts and minds of some. When MONTREAL CANADIENS hockey great Howie MORENZ died in 1937, his funeral service was held at the Montréal Forum before 15 000 faithful fans. And when the venerable Forum closed in 1996, after 72 years of continuous operation, the event was attended with all the pomp, ceremony and symbolism typically associated with the de-consecration of a major religious building - a vivid acknowledgement of the mythic status this building had achieved. How many other buildings have aroused such broadly based enthusiasm? Not only major league sports facilities can achieve such exalted status however. In his book Home Game, Ken DRYDEN showed how the small, ubiquitous Quonsethut-type arenas that dot the Canadian landscape have served as true cultural centres, the glue that binds many small communities together.

In spite of their popular appeal and the devotion of their patrons, the architecture of sports facilities has been little studied. Hence, Canada's leading contribution, notably to the early design and development of skating rinks and hockey arenas, has gone largely unnoticed. The world's first covered skating rink and hockey arena were built in Québec City and Montréal respectively, while Canada's highly developed indoor curling rinks were the envy of visiting Scottish curlers in 1902.

Yet architecture is not a requirement for playing sports. Sport existed, and continues to exist, in the absence of buildings in which games may be played, as the following recollection of a Prairie baseball enthusiast circa 1910 makes clear: "Every town would have a pasture with a chicken wire backstop, and when you was gonna have a game you'd chase the town cows off it and scrape up the cow plops and that was about it." In Canada the earliest buildings for sport were erected in the mid-1800s for the private use of subscribing club members who had the wealth and leisure to indulge in such activities. Towards the end of the century a number of factors influenced the demand for further sports facilities, including the growth of Canada's urban population, their increased wealth and leisure time, and the professionalization of sport. These led to the construction of commercial buildings in which to exercise and view sport, and to sports and recreational structures provided by civic governments as services to citizens and embellishments to the city.

Sports facilities have almost always been situated close to their patrons, whether club members or fans. The earliest skating and CURLING rinks were located within the downtown core of 19th-century cities, usually along public transportation routes. This trend continues to this day. The proliferation of the automobile and the growth of suburbia in the post-war era encouraged some owners to build arenas and stadiums outside the city centre, closer to their middle-class patrons, who prized easy access by car and ample parking.

Today's arenas and stadiums typically comprise a playing surface enclosed by staggered rows of seats, pitched at an angle of 30° to 35° to allow spectators better sight lines, and spanned by a roof built with a variety of possible materials and structural systems. All such buildings owe their form and function to arenas perfected by the ancient Romans over 2000 years ago. Simple structures composed of grandstand and playing field, roofed or out-of-doors, continue to be used in both large and small communities. Major-league sports facilities have grown in size and sophistication, in step with the growing popularity and commercialization of professional sport, and in order to accommodate better an increasing variety of events, further blurring the line between sport and entertainment.

Economic and urban historians have noted that the presence of a professional sports franchise, and its requisite arena or stadium, has become the hallmark of every major North American city. More and more Canadian cities are being defined by the sports palaces they build; Montreal's Olympic Stadium, Toronto's Skydome and Calgary's Saddledome are a few of the more striking examples. The real or imagined economic "spin-off" to the host community resulting from the operation of a major-league facility has become the central argument used by team owners in lobbying governments to divert public funds to their struggling or threatened operations. More recently this discourse has taken on nationalistic overtones, particularly regarding Canada's "national" game, HOCKEY.

Sports sociologists have charged that the new arenas and stadiums are fundamentally different from the idiosyncratic, fan-driven buildings that they have replaced. The new buildings, they claim, are not built for the loyal fan but for a mobile and affluent consumer. The homogeneity of experience that they find in these new buildings is for them symptomatic of corresponding changes to the sports themselves (particularly hockey) and, more generally, of the detachment of sport from both place and civic history.

Baseball

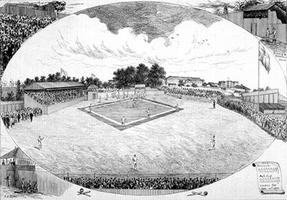

The earliest baseball park in Canada was Tecumseh Park, built in London, Ont, in 1877 for the London Tecumsehs baseball team. Constructed at a cost of upwards of $3000, the Canadian Illustrated News pronounced it "without doubt the best for the purpose in the Dominion." Not much more than a fence to define the playing area (and to keep out stray cattle that might otherwise wander onto the field), it also included a covered grandstand for 600 and a press box equipped with a telegraph wire so that scores from other games could be announced. Like so many of these early structures, this ballpark was constructed of wood; it was either not meant to last or was built so as to be easily taken apart for transport to a new locale. Baseball clubs were notoriously unreliable in the early years of professional baseball in North America, frequently folding or changing cities, while most baseball grounds lasted no more than 5 or 6 years in the 1860s and 1870s. Similar ballparks were erected in Toronto (Sunlight Park, 1886) and Montréal (Atwater Park, 1890) - most likely without the aid of architects.

Hanlan's Point Ball Field was home to Toronto's minor-league Maple Leafs, from 1897 to 1901, and again from 1909 to1925. The owner of the field, Lol Solman, also had an interest in the Toronto Island Ferry Service, which patrons had to use in order to attend games. Solman merely adapted a practice common in the United States whereby trolley companies purchased baseball teams in order to profit from trolley fares to the playing field, conveniently located along their own lines, as much as from admissions to the game itself.

In 1926 the TORONTO MAPLE LEAFS moved into Maple Leaf Stadium on Lakeshore Drive in Toronto, a long home run from Hanlan's Point. Designed by architects Chapman, Oxley & Bishop at a cost of $300 000, its two-storey covered grandstand held nearly 20 000. An arcaded upper level traced the first and third base lines, forming a wide "V" with its rounded point at home plate. A planned upper deck was never realized in the absence of a major league team capable of drawing the larger crowds necessary to fill it.

The basic components of this building were repeated in Montréal at De Lormier Downs Stadium (Hector Racine Stadium). Designed by architect John S. Archibald in 1927, the materials included reinforced concrete, faced with brick and stone on the exterior, and steel trusses supporting a cantilevered roof over part of the grandstand seating. The stability and popularity that baseball had achieved by this date is reflected in the greater capacity and more permanent materials of these buildings.

Major-league baseball did not arrive in Canada until 1969, when the MONTREAL EXPOS began to play at Jarry Park, a pre-existing ballpark that was retro-fitted to boost its seating capacity to 28 000. Baseball's popularity across Canada may also be gauged by the quantity of ballparks for minor-league teams located in every city capable of supporting one, including Municipal Stadium in Québec City, Foothills Baseball Stadium in Calgary, John Ducey (Telus) Park in Edmonton, and Nat Bailey (Capilano) Stadium in Vancouver. Seating about 7000 spectators, these intimate ballparks typically place the fan close to the play and to one another, while still maintaining a visual connection to the surrounding city or landscape, features that have again come into vogue in new stadium design, such as Camden Yards in Baltimore and a 1997 proposal for a downtown Montréal stadium.

Football

Many of Canada's FOOTBALL stadiums, such as Vancouver's Empire Stadium (1954), Montréal's Olympic Stadium (1976), and Edmonton's Commonwealth Stadium (1978), were originally constructed for Olympic or Commonwealth Games and subsequently re-cycled at games' end. The Montréal Automotive Stadium, or Autostade, temporary home to the Canadian Football League (CFL) Alouettes, was designed by Victor Prus and Maurice Desnoyers and completed in 1966 for EXPO 67. To allow the stadium to be dismantled and re-erected on a new site the architects employed a segmental structural system comprising 19 individual but linked grandstands, each 40 seats wide. BC Place in Vancouver (Phillips Barratt Architects, 1983) was built as part of an urban renewal plan in anticipation of the world transport and communication fair EXPO 86. It was the first covered stadium in Canada, and when completed had the largest air-supported plastic roof in the world. The stadium's four-storey reinforced concrete frame measures 236 metres by 195 metres and is topped by a dome made of high-strength fabric reinforced with cables. It is an airtight building which remains inflated over its playing field of synthetic grass through internal air pressure. Montréal's Olympic Velodrome, originally a venue for cycling, is now the Biodome, an environmental ecomuseum.

Montréal's Olympic Stadium, designed by French architect Roger Taillibert, must be the most vilified stadium ever constructed. Plagued by cost overruns (the final price tag is now over $1 billion), dogged by political scandals and structural defects, the building's hulking concrete mass has not proved popular with Montréalers. Although successful in accommodating the tens of thousands of fans who attended a wide variety of sporting events and galas during the 1976 Summer Olympic Games, it has not served its subsequent users as well; both major-league tenants, the Montreal Expos and MONTREAL ALOUETTES, are currently exploring, or have secured, more intimate stadiums closer to downtown. Few sports stadiums in Canada however, before or since, can claim its dynamism or formal beauty.

Toronto's Skydome is the first purpose-built major-league baseball stadium in Canada and the first domed stadium in the world with a fully retractable roof. (The first indoor stadium, and the first to introduce artificial grass, was the Houston Astrodome in 1965.) Designed by architect Rod Robbie and engineer Michael Allen and opened in 1989, the Skydome also serves as a venue for the Argonauts of the CFL. Its domed roof protects its more than 60 000 spectators from the elements and can be retracted in 20 minutes to allow natural light into the stadium. Constructed at a cost of some $500 million, the complex incorporates an 11-storey, 360-room hotel (with 71 rooms overlooking the playing field), a 600-seat restaurant, a health club, a television station and a sports and entertainment area, in addition to its playing surface. "It's not a baseball stadium any more," claims its architect. "It's a pleasure palace."

Swimming

Temporary bathing pavilions constructed of wood had been built in various locations during the 1800s, but only in the first decades of the 1900s were more permanent structures for swimmers erected. They were of two types: bathing pavilions, usually situated beside a natural body of water; and public baths, swimming pools within purpose-built structures located in the inner city.

Bathing pavilions tend to be long low buildings, arcaded at ground level, and frequently punctuated by one or more towers. Such a building was built of concrete along Vancouver's English Bay in 1909, replacing an earlier wooden structure. The Sunnyside Bathing Pavilion along Toronto's Lakeshore Drive was designed in an Italianate style, of painted stucco over concrete and brick, by Chapman, Oxley & Bishop (1922). In addition to providing shelter and facilities for changing and refreshment, these buildings also served as stage sets that established a scale and ambiance for the pleasurable activities of their patrons.

The series of public baths constructed in Montréal's inner city from the 1910s to the 1930s, and designed by some of the leading architects of their day, represent a remarkable gift from the city to its people. Ranging from the grandiose Beaux-Arts classicism of Marius Dufresne's Bain Maisonneuve of 1914-16 to the sleeker and more restrained Bain Généreux of 1926-27 by Jean-Omer Marchand, with its astonishing reinforced concrete interior, the baths provide for the exercise and hygiene of their neighbourhood users while also serving as civic embellishments.

Curling

Canada's long cold winters made it a natural site for the popularization of curling, ice skating, and hockey. Covered rinks were first built to escape the coldest weather and to allow for evening competition and social events. The first indoor rinks, for curling, appeared as early as 1837, although many of these probably consisted of rinks laid down within existing barns or sheds. By 1870 purpose-built curling rinks were already quite common, housing 2 to 8 sheets of ice within sheds illuminated by windows along one or both of their long sides. Many early curling rinks were in fact multi-use buildings. They could also be used for ice skating, and later hockey, and often incorporated bowling alleys, archery ranges, and reception rooms for the comfort of their wealthy private members.

The method of spanning the ice surface and providing for spectators varied. For example, the interior of the Thistle Curling Club of Montréal, erected in 1870, consisted of a flat roof supported throughout its length by columns separating two sheets of ice. Spectators watched from either end of the rink or from the narrow raised surface between the ice sheets. Users entered through a two-storey clubhouse which provided offices, changing rooms and reception rooms with windows overlooking the ice surface.

Column-free interiors and wider spans were first realized through arched wooden trusses or traditional barn construction which allowed for raised, cantilevered galleries for spectators, as at the Toronto Curling Club Rink of 1877. Curling rinks attained quite spectacular dimensions in the late 1800s. The Granite Club Rink in Toronto, designed by architect Norman B. Dick in 1880, comprised a shed with six sheets of ice and a two- storey brick-faced clubhouse. The building rose some 50 feet over an ice surface measuring over 20 000 square feet. With its basilical form, buttressing side aisles, clerestory windows, and six tall arched windows at one end, it presented an imposing form within 19th-century Toronto which could then boast few buildings of comparable size.

Ice Skating

The first covered skating rink in the world was constructed in Québec City in 1852. Located on the south side of the Grand-Allée, the Québec Skating Club was a two-storey pitched-roof building. Its long rectangular skating surface was bisected by a row of columns supporting the relatively low roof, giving it the appearance of a curling rink, for which it may also have served.

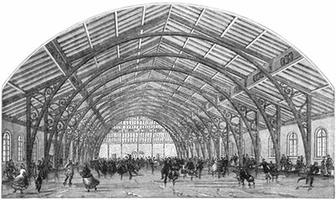

Two types of skating rinks were developed in Canada during the last half of the 1800s. The Victoria Skating-Rink constructed in Montréal in 1862 and designed by Lawford & Nelson, Architects, best characterizes the first type: a long (252' x 113'), two-storey brick building with a pitched roof, 52-feet high, supported on the interior by elegantly curving wooden trusses springing from the ground and spanning the entire width. The ice surface measured 200' x 85' (the approved dimensions for today's NHL arenas) and was surrounded by a 10-foot wide platform or promenade, raised about a foot above the ice, on which spectators could stand or skaters rest. Tall round-arched windows punctuated its long sides and illuminated its interior, while evening skating was made possible by hundreds of gas, and later electric, fixtures. The basic requirement for this type of building was a shed covered by a long, wide-span roof. Possible models that architects might have looked to for inspiration are military drill sheds, first constructed in Toronto, Hamilton and London beginning in 1863, and train sheds, which by the mid-1800s had reached spans of nearly 100 metres.

By about 1880 membership in the Victoria Skating-Rink, "the largest and best skating rink in Europe or America," had reached 2000, mostly drawn from Montréal's upper classes, who had the leisure time to participate in the fancy-dress balls which were a regular feature at the rink. On 3 March 1875 the rink hosted the first hockey game played according to rules resembling today's, contested by two teams from McGill University. In 1893, when the first Stanley Cup finals were played there, the building had gained an elevated balcony for additional spectators and a projecting loge, precursor of today's luxury boxes. The basic form of this building was repeated in dozens of examples throughout Canada, including the Québec Skating Club Rink, Québec City (1877), by William Tutin Thomas, Architect; the Granite Club Ice Rink, Toronto (1880), by William B. Dick, Architect; and the Sherman (Calgary Auditorium) Rink as late as 1904; it was then adapted and enshrined in the hundreds of Quonset-hut arenas that continue to be built across the country.

The second type of covered ice-skating rink, a circular or octagonal dome-topped and centrally planned building, has more in common with concert halls such as the Royal Albert Hall in London of 1867-71, and appears to have been more popular in eastern Canada. The Victoria Skating Rink at Saint John, New Brunswick, designed by Charles Walker and constructed 1864-65, may be the most spectacular example of this model. More than 160 feet in diameter and some 80 feet high, the building's exterior was dominated by a monumental dome topped by a cupola and an entrance in the form of a triumphal arch. On the inside a conical wooden structure descended in a tapering spiral from the centre of the roof to the ice surface, containing within it viewing platforms and a stage for musicians who sometimes played accompaniment for the skaters. An article in the Saint John Morning News published the day after the building opened offers a possible insight into this building's unusual form. It explains that "The excellent ventilation and the style of the building is calculated to free the air from that dense, unpleasant atmosphere which sometimes pervades skating rinks constructed on a different principle". Nevertheless, skating rinks on this plan did not proliferate, likely owing to their limited flexibility to other functions, notably hockey.

Hockey

The Westmount (Montréal) Arena, possibly designed by Montréal architect R. M. Rodden (or Cajetan Dufort, one of the investors) and completed in 1898, was the first purpose-built hockey arena in the world. Skating rinks constructed earlier in the century had been employed for the first indoor hockey matches. These buildings could accommodate as many as 3000 standing spectators, but the cramped spaces of the promenades that encircled the ice of these early rinks afforded limited views. The Westmount Arena combined seating for 6000 in a continuous graded grandstand around an ice surface enclosed by four-foot high boards. (Earlier rinks in Ottawa and Kingston had introduced 12-inch-high boards.) It was purpose-built also in the sense that its owner, the Montréal Arena Company, had been formed specifically in order to profit from the growing interest in amateur hockey by constructing an arena which would serve as venue for such games.

Indoor rinks helped increase the popularity of hockey for players and spectators alike by protecting them from the elements. They also had a direct impact on how the game was played. The more restricted indoor ice surfaces, as compared with frozen streams and lakes, led to a decrease in the number of players per team, from 8 or 9 in 1875 down to 6 by 1913. The change from rubber ball to puck and the introduction of boards to protect spectators from flying balls and bodies in turn affected the evolution of hockey by innovative players who introduced puck control, sliding passes, and carom passes off the boards. These developments further distinguished hockey from those games out of which it is reputed to have developed: shinty, bandy, hurling, and field hockey.

The next generation of hockey arenas followed the creation of the NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE (NHL) in 1917 and, mirroring the experience of baseball stadiums, their greater capacity suggest the increased popularity of the sport. The Montréal Forum, designed by John S. ARCHIBALD in 1923-24, provided seating for 10 300 under a shed roof supported by interior columns that were only removed during renovations in 1968. Toronto's Maple Leaf Gardens, designed by Ross & Macdonald in 1929- 31, originally accommodated 13 000 under a domed roof offering unobstructed views from every seat. Both buildings were centrally located on downtown streets served by bus or trolley lines and incorporated other attractions such as bowling alleys, restaurants and ground floor shops. Maple Leaf Gardens is also noteworthy for its early accommodation of the media. Foster HEWITT's national radio broadcasts of Maple Leaf games originated from a booth (named after the gondolas that hung beneath dirigibles) suspended 56 feet over centre ice and which had been planned as an integral part of the building from an early date.

Equipment for making artificial ice had been installed in rinks in the United States as early as 1895 but was only introduced to Canada in 1911 by Frank and Lester Patrick in their two new arenas in Victoria and Vancouver. This feature further popularized hockey by allowing for an extended season and ensuring that games would take place as planned regardless of the weather. Both the Montréal Forum and Maple Leaf Gardens were equipped with ice-making equipment. This consisted of "miles" of thin, coiled metal pipes embedded in the arena floor through which a continuous flow of cold brine was passed, refrigerating the floor and causing water spread over it to freeze, usually to a thickness of one inch for hockey. The arrival of ice resurfacers in the early 1940s, invented by and named for Frank Zamboni, assisted the maintenance of ice surfaces and the speed of the game. Electric timing devices, such as the one installed in Maple Leaf Gardens, were developed in the late 1920s and allowed spectators to follow events on the ice better.

A major factor determining the design of arenas is the method of roof construction. An innovative system was employed by Graham McCourt Architects at the Calgary Saddledome. Completed in 1983 for use at the 1988 Winter Olympics and now home to the NHL CALGARY FLAMES, the Saddledome is both an exciting form evocative of Calgary's western heritage and a functional enclosure. Pre-cast concrete panels are suspended from hanging steel cables which follow the contours of the seating. Sightlines are excellent, while the roof's concavity reduces the interior volume, and consequently the building's heating costs.

Vancouver's GM Place (1995), the Corel Centre in Ottawa (1996) and Molson Centre in Montréal (1996) are part of a North American-wide boom in arena construction. From the late 1980s to the year 2000 more than 20 NHL arenas alone will have been constructed. These state-of-the-art facilities, some costing over $200 million, actually trace their origins to covered skating and curling rinks first constructed in Canada in the mid-1800s. They still share characteristics with early skating rinks. Many of these new buildings replace existing facilities, whose primary fault lies in their inability to generate adequate income (said to be necessary to pay skyrocketing player salaries) through private boxes, executive seating and interior advertising. These new multi-purpose entertainment venues are adaptable to many functions and are superior acoustically. They are also among the first arenas designed to maximize both spectators sightlines and those of the television camera.

See alsoSPORTS HISTORY.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom