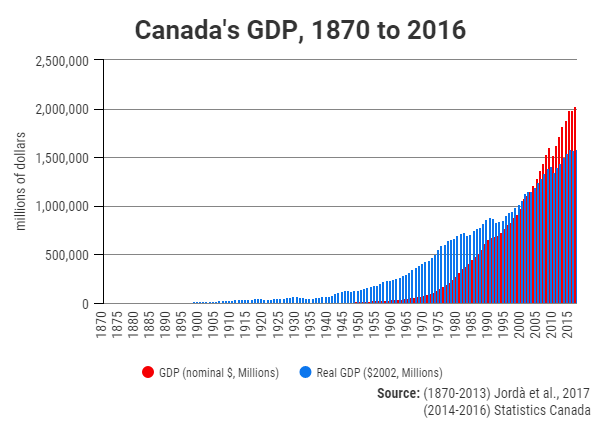

The underground economy is defined by the Canada Revenue Agency as “economic transactions in goods or services which are unreported, resulting in failure to comply with tax laws administered by the Canada Revenue Agency.” (See also Taxation in Canada.) Statistics Canada reported that the annual 2021 estimate for the underground economy was $68.5 billion. This accounted for 2.7 per cent of Canada’s total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2021. (See also Economy.)

What is the Underground Economy?

The underground economy refers to economic transactions among individuals which are designed to escape detection. Technically, the underground economy includes all illegal transactions, e.g., prostitution and drug transactions as well as hidden or informal evasions of taxation on otherwise legal activities. For example, a homeowner may hire someone to repair a roof. This is a legal transaction and is routinely reported when the person doing the repair declares the payment as income. However, the labourer may ask for and receive cash payment in which case the income is not declared in order to evade tax. Individuals in various lines of work can potentially underreport income if payment is received in cash.

Measuring the Underground Economy

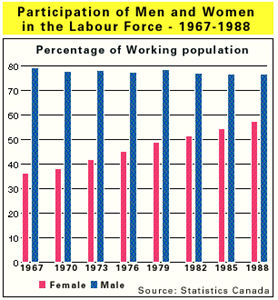

Law enforcement and taxation officials readily admit that there is a large underground economy but cannot agree on its size. Because of its very nature the size of the underground economy is difficult to measure, but there is evidence to indicate that in Canada and elsewhere it has grown recently. Underground activities do not enter the official statistics on GDP. Those employed in the underground economy may be counted as unemployed in the official labour force statistics. If they hold a regular job and also work in the underground economy, then the total quantity of labour input is incorrectly measured.

Because a large fraction of transactions in the underground economy appears to be in cash, measuring cash holdings is one method of estimating the extent of the transactions (see Money in Canada). Basically, this involves estimating the cash needed for regular transactions and then determining the difference between this amount and actual cash used. This method has been used to estimate the size of the underground economy in Canada, the United States and other countries. These estimates explain the apparent paradox in the published data on cash holdings. Although it has been widely predicted that the growth in the use of credit cards and electronic fund transfers would lead to a cashless society or one in which cash is less important, currency holdings have not declined. Economists assert that this results from the diversion of increasing quantities of cash for use in the underground economy.

Black Market

There are frequent references to the sale of drugs and other controlled commodities on "the black market," a term that aptly describes the illegal component of the underground economy. Officially, such transactions are unreported. However, there is another meaning to the expression black market. If a particular commodity is the subject of legal price controls, e.g., food during wartime, then transactions at illegal prices are usually referred to as black-market transactions. (See also Wartime Home Front.) An official report, if it is made, will indicate that the transaction took place at the legal rather than the actual price.

Tax System

Legal activities conducted underground to escape taxation appear to be the fastest-growing component of the underground economy, largely because of Canada’s tax system. The potential gains from illegal tax evasion are greater at high tax rates. If rising incomes push more people into higher tax brackets, and if there are no changes in the penalties or the degree of enforcement of tax laws, an increase in unreported income can be expected; this is exactly what has happened so far.

The growth of the underground economy has important implications for the Canadian tax system, which relies on self-assessment and involves relatively little direct scrutiny of individual tax returns by taxation officials. Continuing growth in unreported income will almost surely lead to changes in this system. In addition, the introduction of the goods and services tax in 1991 is estimated to have increased the size of the underground economy by 0.8 per cent in 1992. If increasing amounts of taxation are being avoided through the underground economy, the tax burden on reported activities will be higher. Taxation officials correctly worry that as taxpayers observe the growth of unreported income in the underground economy more of them will be tempted to try to conceal income.

It has been observed that the growth of the underground economy has paralleled the growth of inflation after the mid-1960s, although there is no concrete evidence to support this point. Inflation is an unlegislated tax which many economists regard as an important factor in reducing social cohesion. It may well be that this unlegislated tax rather than high rates of taxation explains the increase in failures to report income.

Approaches

Different methods have been proposed to deal with the underground economy. By auditing more tax returns and by increasing the penalties for nonreporting and other forms of tax evasion have been suggested. Another alternative would be to lower tax rates, thereby reducing the incentive to evade taxation. The 1986 tax reform bill in the US lowered personal tax rates and similar tax legislation to reduce high marginal tax rates was introduced in Canada in 1988. (See also Taxation in Canada.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom