The Canadian Encyclopedia invites you to discover eight Québécois women with exceptional careers. Politicians, activists, social workers or accomplished artists, these women left an indelible mark on the history of Québec and Canada.This exhibit features short biographies that recount the lives and legacies of these women. The first section concentrates on women who not only dedicated their lives to advancing women’s rights, but also to improving social and economic conditions for the entire population. The second section is dedicated to those women who through their humour, brush, pen or voice overturned artistic conventions. The magnificent acrylic portraits were created by painter Marie-Josée Hudon, director of the Musée des Grands Québécois. A Historica Canada partner, this cultural and educational organization aims to promote human heritage through the display of travelling exhibits.

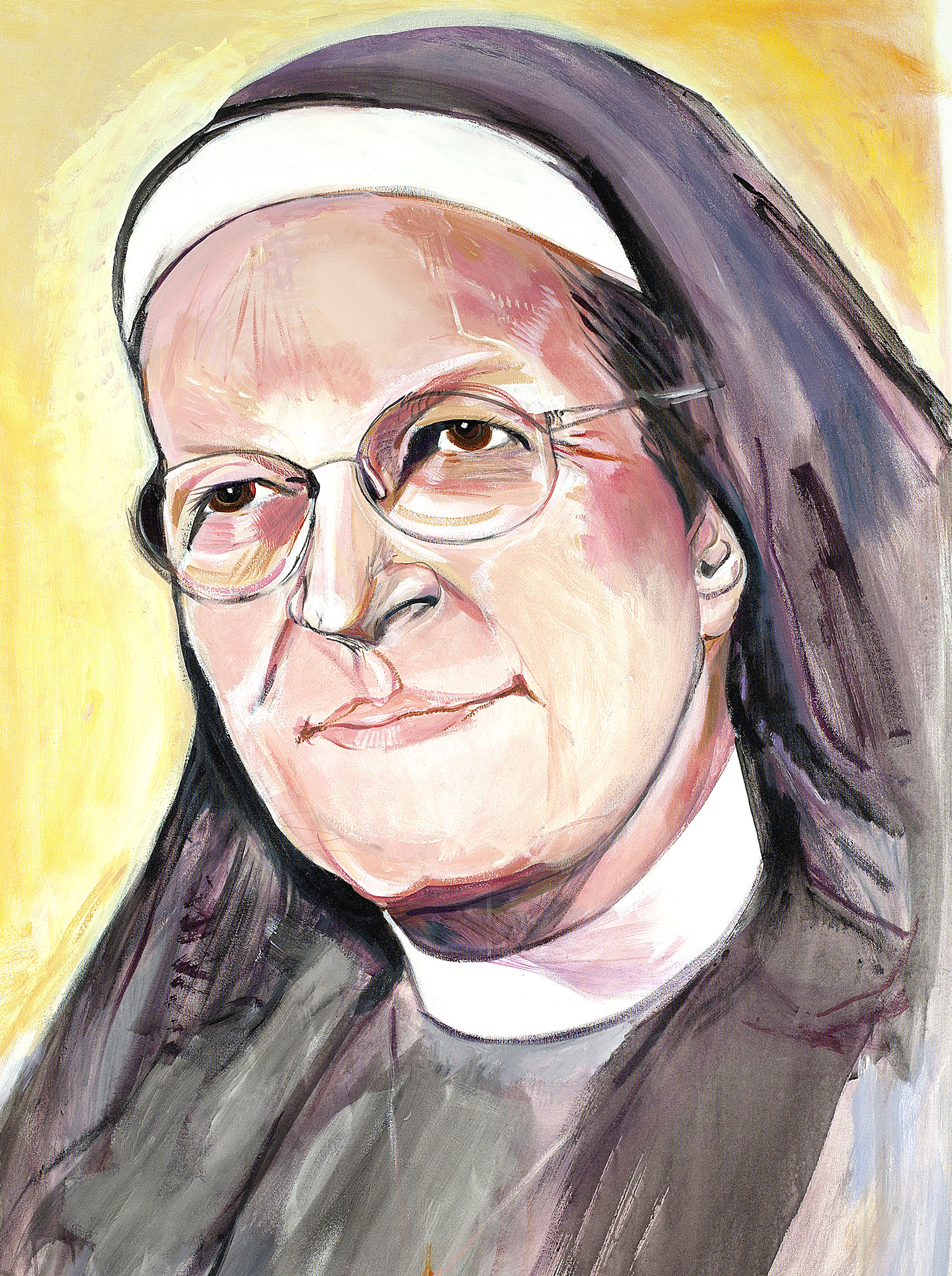

Marie-Joséphine Gérin-Lajoie (1890-1971)

Gérin-Lajoie is the daughter of Marie Gérin-Lajoie (née Lacoste), a pioneer of the women’s rights movement in Québec. She was the first French Canadian woman to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree (1911). She ranked first at the provincial level, ahead of her male colleagues. Though women were not admitted to francophone universities at the time, Gérin-Lajoie studied social sciences on her own time by reading broadly. She wrote for La Bonne Parole, the Fédération nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste’s newspaper, and was actively involved in the organization itself. In 1918, she moved to the United States and enrolled at Columbia University in New York to study social work.

When she returned to Québec, Gérin-Lajoie worked with poverty-stricken families in Montréal and founded the department of social services at Hôpital Sainte-Justine. Keeping in line with the type of work in which her mother and aunts (Justine and Thaïs Lacoste) engaged, Gérin-Lajoie sought to improve the lives of women and families. In 1923, she took the veil and founded a religious community, the Institut Notre-Dame-du-Bon-Conseil. Focused on community action and social service, as well as domestic and social education, the organization was committed to fighting social and economic inequality. Over the years, the organization has created many community centres, playgrounds and shelters in Montréal’s less privileged parishes.

Gérin-Lajoie also opened a school of social work in 1931 in order to train social workers. In 1939, she contributed to the creation of the École de service social at Université de Montréal, where she taught for many years.

Thérèse Casgrain (1896-1981)

A founding member of the Provincial Franchise Committee for women's suffrage in 1921, Casgrain campaigned ceaselessly for women's rights in Québec. She headed the Ligue des droits de la femme for 14 years (1928–1942), which attained not only the right for women to vote at the provincial level, but also significant social and legal reforms. In 1940, the Quebec Liberals, led by Adélard Godbout, passed the women’s suffrage bill, and women obtained the right to vote in Québec’s provincial elections.

During the Second World War she was one of two presidents of the Women's Surveillance Committee for the Wartime Prices and Trade Board. In a 1942 federal by-election, Thérèse Casgrain was the Independent Liberal candidate in the Charlevoix–Saguenay riding, the seat held earlier by both her father and husband. She finished second.

In 1946, disillusioned with the Liberals, she joined the socialist Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (now the New Democratic Party). In 1948, she was chosen as the national vice-chair of the CCF, the only woman on its executive. From 1951 to 1957, she served as leader of the Québec wing of the party (known from 1955 as the Parti social démocratique du Québec), making her the first woman in Canadian history to head a political party.

In Québec, along with intellectuals and union activists she helped mobilize opposition to Premier Maurice Duplessis. In 1961, she founded the Québec branch of the Voice of Women (see also Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom) to protest the nuclear threat. She was a founder of the League for Human Rights (1960) and of the Fédération des femmes du Québec (1966). In 1970, at age 74, she was appointed to the Senate as an independent and served for nine months before reaching the mandatory retirement age of 75 in July 1971.

Notre véritable travail ne fait que commencer. Le vote est un moyen, et non pas une fin. ‒ Thérèse Casgrain, à la suite de l'obtention du suffrage féminin au Québec en 1940.

Simonne Monet-Chartrand (1919-1993)

A woman of passion and conviction, Simonne Monet-Chartrand actively supported many causes, including labour and union rights, feminism, human rights, and pacifism. She co-founded the Fédération des femmes du Québec (FFQ) and Concordia University’s Simone de Beauvoir Institute.

From the time of her secondary studies, she was involved in la Jeunesse étudiante catholique (JEC), and in 1937, she became the president of the female branch of that organization. It was at the JEC that she met Michel Chartrand, the union leader and activist whom she would marry in 1942. From 1939 to 1942, Monet attended the Université de Montréal, where she studied French-Canadian literature and Canadian history, and took courses with such notable figures as historians Lionel Groulx and Guy Frégault.

In 1942, during the conscription crisis, she joined the Bloc populaire canadien. In 1949, she could be found at her husband's side on committees supporting the asbestos strikers, and later, as a member of the socio-political committee for the Centrale des enseignants du Québec (Québec Teachers' Union). In 1961, she joined the pacifist movement Voix des femmes, and in 1962 helped to organize the Train de la paix, a delegation of the movement which presented their demands to the federal government. In 1968, she co-authored a report submitted to the Royal Commission on the Status of Women. Monet-Chartrand joined the League of Human Rights (Ligue des droits de l’homme) in 1963 and was associate director from 1975 to 1978. In 1977, she became associate director of the League of Rights and Freedoms.

Monet-Chartrand became a media personality in the 1950s as a consultant and panellist for Radio-Canada broadcasts. In the 1960s and 1970s she was a writer and researcher for religious broadcasts and women’s broadcasts (Femina, Femmes d'aujourd'hui, 5D) at Radio-Canada. In addition to numerous writings for conferences and columns in such publications as La Vie en Rose, Les Têtes de pioche, and Châtelaine, Monet-Chartrand published four volumes of her autobiography, Ma vie comme rivière (1981–92).

Personne ne peut vous enlever votre liberté de penser. Vous pouvez être conseillé, éclairé par d'autres, mais ne laissez jamais quelqu'un penser pour vous. ‒ Simonne Monet-Chartrand

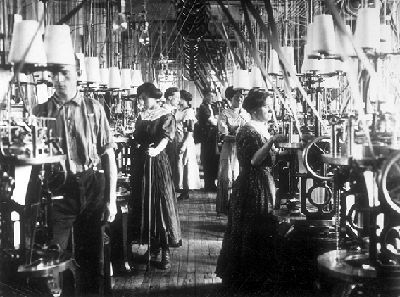

Madeleine Parent (1918-2012)

In 1936, Parent enrolled at McGill University and earned a bachelor of sociology. At a meeting of the Civil Rights League after she graduated, Parent met Léa Roback, a union organizer who convinced her to join the union movement.

In 1942, barely 24 years old, she led the union movement at the Valleyfield and Montréal factories of the powerful Dominion Textile company under the banner of the United Textile Workers of America (UTWA). That same year, Parent met Kent Rowley, who would not only become her husband but her colleague in arms. In June 1946, with Dominion Textile still refusing to recognize the union, a strike was called that would last 100 days. Maurice Duplessis, then premier of Québec, immediately declared the strike “illegal.” Parent and Rowley were arrested on 13 August along with all the other union leaders, but the 6,000 workers would win this fight and create their union.

The UTWA was affiliated with American unions. In 1952, UTWA heads signed an agreement with Dominion Textile, in accordance with demands imposed by Duplessis. Under pressure from these unions, which accused them of being Communists, Parent and Rowley were thrown out of the UTWA and left for Ontario. There Parent organized the Confederation of Canadian Unions with Rowley in 1969. The purpose of this organization was to repatriate Canadian unions that held American allegiances.

Parent fought on many fronts, particularly for women. She was a founding member of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (NAC) in Ottawa. She represented Québec between 1972 and 1983. During that period, she defended the rights of Aboriginal women and fought for equal pay. She was also involved with the Fédération des femmes du Québec and participated twice in the World March of Women in 1995 and in 2000.

Parent died the night of 11–12 March 2012, leaving behind the legacy of a “fighter” who knew how to make people understand the importance of unions. Devoting her life to fighting for social justice, she was dauntless in facing the power of authority, keeping her head high and accepting the consequences of her actions.

Marcelle Ferron (1924-2001)

After studying at the École du Meuble in Montréal and the École des beaux-arts in Québec City, Ferron became part of Les Automatistes, signing that association's polemical manifesto, Refus Global, in 1948. She is the only female artist who signed the legendary document. Her non-figurative paintings were hung in all the major Automatiste exhibitions. She lived in Paris from 1953 to 1966 and continued to show in avant-garde exhibitions, including the 1961 Sao Paulo Biennial in Brazil, where she won the Silver Medal.

The paintings of this dynamic artist became progressively more forceful. Vibrant colours and larger, fluid forms dominated the canvas. Like fellow automatistes Boudruas and Jean-Paul Riopelle, Ferron applied paint to the canvas thickly, with great intensity and straight from the tube, often using a palette knife rather than a brush. In “Lascive” (1959), for instance, bright white bars of paint push vertically into the foreground, streaking and blurring into horizontal bars of purple and blue. “Les barrens” (1961), on the other hand, has jagged, congested conflagrations of red, blue, purple and black against a spacious, open white ground.

After 1964, her interest in light was effectively translated into a new medium — stained glass — examples of which can be seen in the Champ-de-Mars and Vendôme metro stations in Montréal. Commissioned in 1966 by the city of Montréal under the mayoralty of Jean Drapeau and installed in 1968 with the help of master glassworker Aurèle Johnson, Ferron’s Champs-de-Mars window is widely regarded as her masterpiece.

Ferron is represented in many Canadian and foreign collections, including the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal, the Museum of Modern Art in Sao Paulo, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and the Hirshorn Museum in Washington, DC.

Rose Ouellette (1903-1996)

At the age of 19, she was noticed by Paul Hébert after performing at the Ouimetoscope and Lune rousse theatres in Montréal. She later met Olivier Guimond (senior), with whom she formed a duo that quickly became popular throughout Québec. This marked the beginning of a prolific career on the burlesque stage, which she pursued well into her old age.

In 1936, Ouellette assumed the role of director of the Théatre national. Under her direction, this theatre experienced a golden age. For 17 years, she performed to sold-out crowds for both matinees and evening shows. The advent of television in 1952 and the development of cabarets sounded the death-knell of the burlesque genre (see French-Language Theatre). In 1953, Ouellette left the Théâtre national in order to join Jean Grimaldi’s company. In 1958, she began performing on the cabaret scene with Juliette Pétrie, Gerry Morelle, Simone Mercier, Gaston Boileau and Louis Armel.

In 1960, she made her television debut on Radio-Canada in a play written by André Laurendeau called Les Deux Valses. She then played small roles in such soap operas as Rue des Pignons, Chère Isabelle, Les Brillant and Les Moineau et les Pinson. On stage, Ouellette proved that she was able to take on more serious roles, notably in the play Un jour, ce sera ton tour, written by Serge Sirois (performed at the Théâtre du Nouveau Monde in 1974). During this time, she pursued her career in comedy and from 1967 to 1993, performed at the Théâtre des Variétés, directed by Gilles Latulippe.

In the early 1990s while approaching her 90th birthday, she went on a tour of Québec with singer Roger Sylvain. She passed away in Montréal at the age of 93. As a pioneer of burlesque theatre and comedy in Québec, Rose Ouellette influenced several generations of francophone artists and comedians.

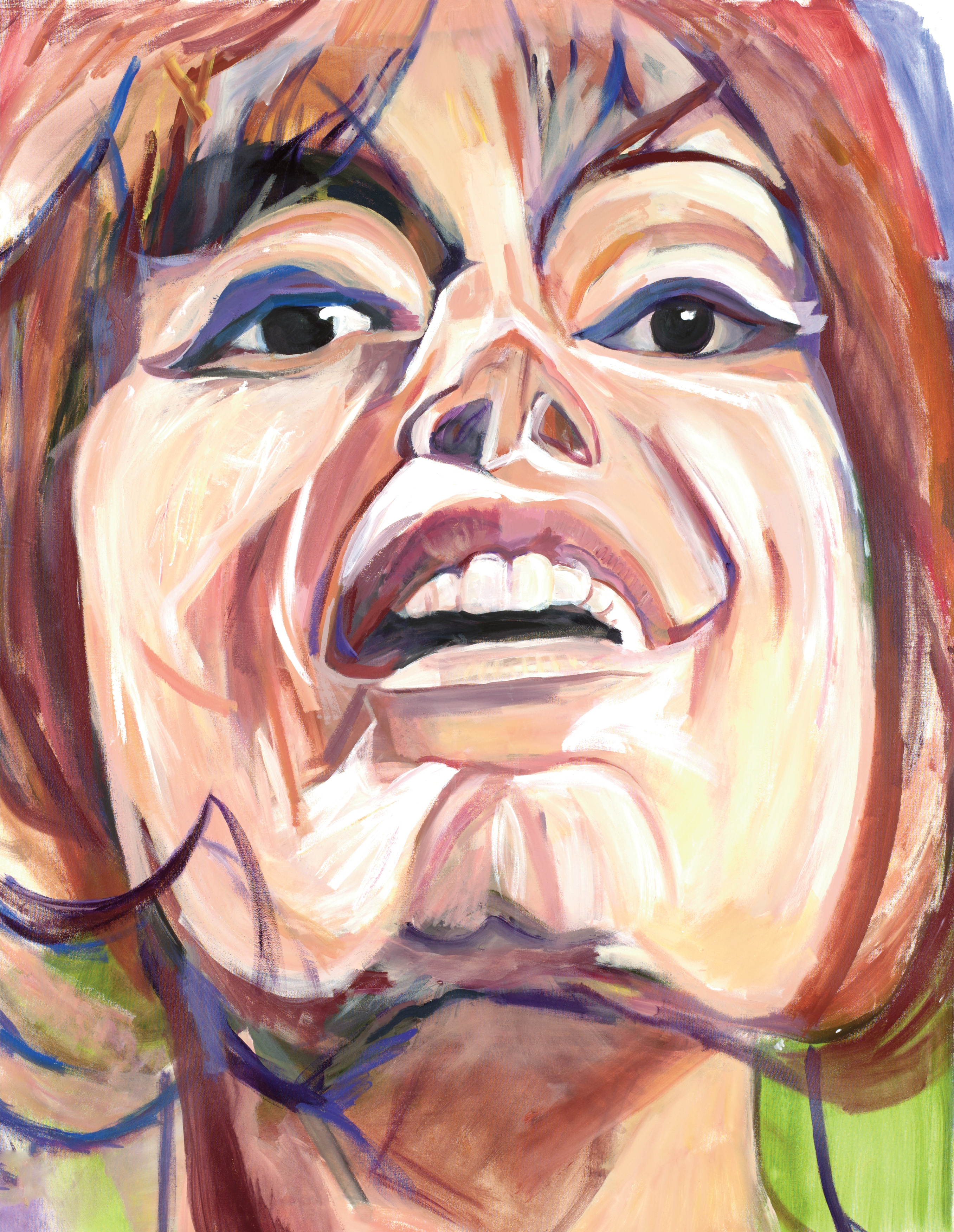

Pauline Julien (1928-1998)

Nicknamed “the passionara of Québec,” the singer Pauline Julien was known for her expressive power and sensitivity — qualities she drew from her experience in both music and theatre. Julien was equally popular in Québec and Europe, and also enjoyed success in English Canada. She introduced the songs of Weill and Brecht to Québec, popularized songs by Raymond Lévesque and Gilles Vigneault, and released 23 solo albums in her lifetime.

Julien’s first two albums, Enfin ... Pauline Julien (1962) and Pauline Julien (1963), along with her performances with Claude Gauthier and Claude Léveillée, and several TV appearances in 1963, established her as a popular and affecting chanteuse. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Julien's repertoire consisted exclusively of songs by Québec writers. In 1968, she began to write song lyrics. From 1977 to 1978 she toured Québec and Europe to great acclaim in support of her album Femmes de paroles (1977).

Her album Charade (1982) included two of her bigest hits: “L'âme à la tendresse” and “Mommy.” In 1986, she announced her retirement from solo performing, but she continued to pursue interesting collaborative performances, such as those with her second husband, poet Gérald Godin. During the 1980s and early 1990s, Julien performed mainly in the theatre, namely in Brecht-Weill's Grandeur et décadence de la ville de Mahogonny (1984), Heiner Müller's Rivages à l'abandon (1990), Victor Lévy Beaulieu's La Maison cassée (1991) and Les Muses au musée at the Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal (1992).

A passionate political activist, Julien was committed to political independence for Québec. She was jailed for protesting the War Measures Act during the October Crisis of 1970. She also took up the feminist cause in the mid-1970s. She introduced the song “La Moitié du monde est une femme” in 1975. Julien appeared at various political rallies and also performed humanitarian work. She travelled to Burkina Faso (1993) and Rwanda (1994). Montréal Centre des arts de la scène Pauline-Julien and Montréal’s Salle Pauline Julien, both devoted to francophone arts, are named in her honour.

Hélène Pedneault (1952-2008)

Passionate about all forms of writing, Pedneault began her career in journalism in the Saguenay after studying literature at the CÉGEP in Jonquière. She gained prominence through her columns, Les Chroniques délinquantes, which appeared in the feminist magazine La Vie en Rose and were published as a collection in 1988 (republished in 2002).

Throughout her career, she wrote numerous editorials and commentaries for such Radio-Canada programs as Christiane Charrette, Indicatif Présent and Pensée libre. Pedneault wrote the lyrics for many songs by Marie-Claire Séguin, Richard Séguin and Sylvie Tremblay, as well as the song Du pain et des roses, which served as the theme for the Woman's March in Québec in 1995. She also wrote for the theatre. Her play La Déposition (published in English as Evidence to the Contrary) premiered in Montréal in 1988. It has since been translated into five languages and has been performed in such countries as France, Italy, Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, Holland and the United States.

Pedneault was a co-founder of Eau-Secours, a coalition for the protection of Québec's aquatic environment. She also co-founded the Council on Québec Sovereignty and served as vice-president to the executive of the board of directors in 2003. She was one of the signatories of the Manifeste pour un Québec solidaire in 2005, which led to the creation of the Québec solidiare party in 2006.

Throughout her career, Pedneault championed the cause of women, endorsing the values of equality, freedom and independence. She died of cancer at age 56 and bequeathed more than 100 books on drama, theatre and art to the Bleviss Family Library at the National Theatre School of Canada. The book Qui est Hélène Pedneault? Fragments d'une femme entière — featuring reflections on Pedneault’s life and work from 68 prominent Quebeckers, including Lise Payette, Suzanne Jacob and André Brochu — was published in 2013.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom