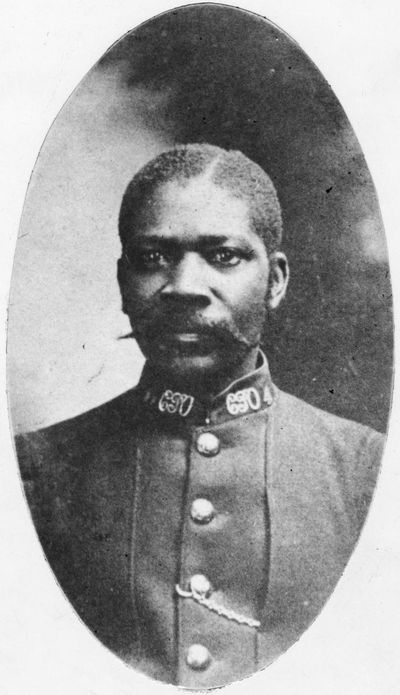

Albert Jackson, letter carrier (born 2 November 1857 in Delaware; died 14 January 1918 in Toronto, ON). Albert Jackson was the first Black letter carrier employed by Royal Mail Canada (see Postal System). Jackson was born into enslavement in the United States and escaped to Canada with his mother and siblings when he was a toddler in 1858. In 1882, Jackson was hired as a letter carrier in Toronto, but his white co-workers refused to train him on the job. While his story was debated in the press for weeks, the Black community in Toronto organized in support of Jackson, meeting with Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald to have Jackson properly instated. Jackson returned to his post days later and served as a letter carrier for almost 36 years.

Early Life

Albert Jackson was one of nine children born to Ann Maria Jackson in Delaware. John Jackson, his father, was a free-born blacksmith. The couple made enough money to pay the man who claimed Ann Maria’s service so that she and their children could live in her husband’s household, although they remained enslaved. When Albert was still a toddler, his older brothers, James and Richard, were sold (see also Black Enslavement in Canada). This traumatic event separated the family and Jackson’s father died of grief in the local Almshouse. After she learned that more of her children were going to be taken to Mississippi by her “owner,” Ann Maria escaped enslavement in Delaware with the remaining seven of her children.

The family first arrived at the home of Quaker abolitionist Thomas Garrett in Wilmington, Delaware. On 21 November 1858, Garrett wrote to African American abolitionist and Secretary of the Pennsylvania Antislavery Society William Still, that he was sending them by carriage to Still’s busy Underground Railroad station.

The Jacksons crossed into Canada, arriving in St. Catharines, Canada West (Ontario) by the end of November 1858, before being sent on to Toronto. They stayed briefly with Thornton and Lucie Blackburn, who had escaped enslavement in Kentucky many years earlier and established Toronto’s first taxi business. Ann Maria eventually rented rooms for her family in St. John’s Ward, the city’s working-class suburb north of Osgoode Hall. The district was home to many recent immigrants, including freedom seekers. Ann Maria and her daughters earned a living washing clothes, while her older boys waited tables. The family was able to send Albert to school. Both Ann Maria’s eldest sons escaped the enslavers to whom they had been sold and made their way to Toronto where James Henry and Richard M. Jackson became well-known barbers.

Career

After finishing his studies, Albert Jackson applied to work as a letter carrier, a government appointed position. At the time, most Black men in Toronto worked as labourers or in the service industry, although there was at least one Black physician and an attorney, several prosperous business owners, and one successful construction company owner (see also Black Canadians; Sleeping Car Porters in Canada).

On 12 May 1882, Jackson was hired, for the federal postal system. However, on his first day on the job, Jackson’s colleagues refused to train him to deliver mail and his supervisor assigned Jackson to a lower position as a hall porter (caretaker).

The insult to Albert Jackson was quickly picked up in the press. On 17 May 1882 The Evening Telegram ran a story with the headline “The Objectionable African.” In it, Jackson was described as an “obnoxious coloured man” whose hiring as a mail carrier had brought on “the intense disgust of the existing post office staff.”

Days later, the Telegram ran an editorial arguing that “Objection to the young man on account of his colour is indefensible… Taxes are not made a penny less to a man because he happens to have dark skin.” The story remained in the press for weeks, with racist attacks on Black people in the streets, and debate swirling through the opinion pages about whether or not Black people were inherently inferior. One editorial explained that, although “inferior races are a fact,” political equality was a reality in Canada. On 29 May, the Black community including several members of the Jackson family held a public meeting at the Richmond Street Methodist Church. They set up a committee to protest the matter. One member, noted local barber and community spokesperson George Washington Smith, published a letter to the editor in which he explained that Black people were as capable as anyone when extended the same opportunities.

On 30 May, Smith led his committee of five Black Torontonians in a meeting with Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald and demanded that Jackson be trained as a letter carrier. With a federal election less than a month away, Macdonald was eager to gain Black voters’ favour (see also Black Voting Rights in Canada), and he instructed the Postmaster to reinstate Jackson and have him trained to deliver mail. Three days after the meeting, Jackson was reinstated as a letter carrier.

After a brief mention in the Globe that Jackson had returned to work “with no objection being raised,” Jackson settled into his job. He worked as a letter carrier for almost 36 years, from 1882 until his death in 1918, delivering mail on a route through Harbord Village.

Personal Life

Albert Jackson married Henrietta Jones on 3 March 1883. The couple had four sons: Alfred, Richard, Harold and Bruce. During his lifetime, Jackson and his wife purchased several homes in downtown Toronto. After his death, Henrietta and her sons bought more property in Harbord Village. She passed away at the age of 99 in 1958 and was interred beside her husband at the Toronto Necropolis.

Legacy

While Albert Jackson’s story was known to family members for generations, it was discussed in Colin McFarquhar’s 1998 doctoral dissertation, and again in historian Karolyn Smardz Frost’s book, I've Got a Home in Glory Land: A Lost Tale of the Underground Railroad (2007), which describes the life of Thornton and Lucie Blackburn. The result of extensive archaeological and archival research, Frost expanded on Albert Jackson’s story after discovering that both his mother, Ann Maria Jackson and his brother, Richard M. Jackson lie in the Blackburn plot at the Toronto Necropolis cemetery.

In 2013, the Canadian Union of Postal Workers created a commemorative poster of Albert Jackson. That same year, a laneway in Harbord Village was named after Jackson. In 2015, The Postman, an outdoor play by David Ferry, was performed on the actual doorsteps to which Albert Jackson delivered mail. In 2017, a historical plaque was placed where the Toronto General Post Office once stood, and where Jackson picked up his deliveries. In February 2019, Canada Post released a stamp depicting Albert Jackson in honour of Black History Month. In 2022, Canada Post inaugurated the Albert Jackson Processing Centre in northern Scarborough, the largest mail-sorting facility in Canada. In 2024, the Government of Canada recognized Jackson as a person of national historic significance.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom