The following article is part of an exhibit. Past exhibits are not updated.

The Inuit knew all along.

On 9 September 2014, Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced the finding of one of Sir John Franklin’s two ships. In 1846, sea ice in the Victoria Strait trapped the British explorer and his men, who were attempting to map the Northwest Passage — a water route linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Lost for some 170 years, one of the vessels had been found.

“This is a great historic event,” Harper said during a press conference. Indeed, locating the HMS Erebus was incredible in that it solved a piece of a very old puzzle. It was remarkable in terms of the science, technology and patience it required. It was significant in terms of further establishing Canada’s identity as a northern nation.

But perhaps most notable is the role Inuit oral history played in finding the ship. In Western culture, oral history is often dismissed as a game of broken telephone — 170 years later, what started off as “The ship is there” becomes “The whip is where?” The Erebus was located in part, however, by consulting these stories.

When oral history is considered, a whole new Arctic reveals itself. The words often used to describe the space — mysterious, inhospitable, unnavigable — no longer apply. Instead, it becomes a place inhabited for roughly 4,000 years, with routes and trails well-travelled long before white men ever left their footprints in the snow.

This exhibit aims to view arctic exploration, specifically attempts at finding the Northwest Passage, through the eyes of the Inuit. It begins with an audio recording of Inuit elder Louis Ameralik and includes a series of maps revealing the differences between how explorers and Inuit view the Arctic landscape.

Louis Ameralik's Story: John Ross

During their search for Franklin’s ships, Parks Canada sought the guidance of Louie Kamookak, an Inuit historian from Gjoa Haven, Nunavut. Kamookak had been gathering stories from elders, in particular tales of Franklin, for over 40 years. Here, in an audio recording of one of those conversations, elder Louis Ameralik tells the story of the Netsilingmiut meeting John Ross and his men in 1830. Ameralik picks up the narrative after Abliluktuq, the first Netsilik Inuk to see Ross’ ship, ran home frightened.

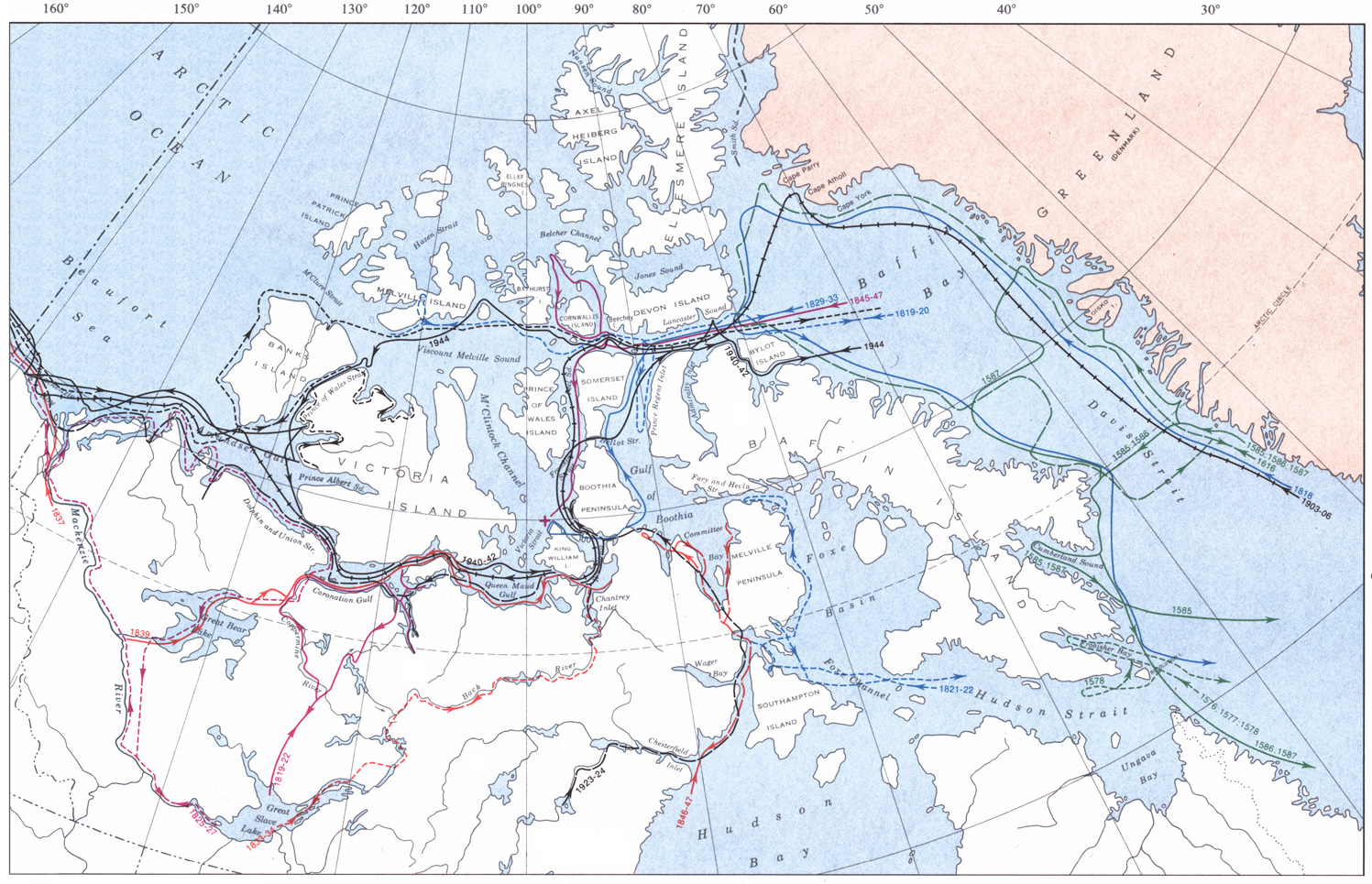

Ross was making his second attempt at finding the Northwest Passage, following a previous attempt in 1818. Others had floundered before him, including Martin Frobisher in 1576; John Davis in 1585, 1586 and 1587; Henry Hudson in 1610, duo William Baffin and Robert Bylot in 1615 and 1616; and Edward Parry in 1819.

Louis Ameralik's Story: Sir John Franklin

Sir John Franklin began his fatal search for the Northwest Passage in 1845, setting sail from England with 134 men aboard two ships, the Erebus and the Terror. (Five men later disembarked at Greenland as they were judged unfit for service.) From Baffin Bay, they headed east through Lancaster Sound, went around Cornwallis Island and then, in the summer of 1846, sailed south through Peel Sound and into the Victoria Strait. There, the ships became trapped in ice off the coast of King William Island. The vessels remained frozen in place while Franklin and other crew members perished. Finally, on 22 April 1848, the remaining 105 men abandoned the ships for the nearest Hudson’s Bay Company outpost, at Great Slave Lake — over 1,300 km away. With them they dragged sleighs mounted with boats, hammers, nails, goggles, biscuits, meat, vinegar and rum.They expected the journey to last three months. None survived.

In the second part of elder Louis Ameralik’s story he describes the trail of bodies and belongings Franklin’s men left behind.

Map: Northwest Passage

For the next 300 years, explorers made similar attempts, each time bumping into islands or turning to port when they should have turned to starboard.

In 1576, British explorer Martin Frobisher set out to find the Northwest Passage , one of the first Europeans to do so. He never made it past the eastern shores of Baffin Island on this voyage, taking a wrong turn up a bay that now bears his name. For the next 300 years, explorers made similar attempts, each time bumping into islands or turning to port when they should have turned to starboard. Then, from 1903 to 1906, Norwegian Roald Amundsen successfully travelled through the Arctic Archipelago from east to west, essentially picking up where Franklin left off. Having made it to King William Island via Peel Sound, Amundsen sailed round the southern coast of Victoria Island via the Queen Maud and Coronation Gulfs, then into the Beaufort Sea.

This map charts several notable Northwest Passage expeditions, from 1576 to 1944, including searches for Franklin’s lost ships.

Map: Traditional Place Names

Much of the Arctic is named after explorers, including many who searched for a Northwest Passage: Frobisher Bay, Davis Strait, Amundsen Gulf, and so on.

Of course, these places, as well as nearby hills, valleys and other landmarks, already had Inuktitut names. Like the stories of explorers, these traditional names have been passed down through oral history over the course of centuries, often containing descriptive information about the location.

Here, a partial map of Frobisher Bay, compiled by the Inuit Heritage Trust, provides an example of some traditional Inuit place names, of which there are thousands throughout the Arctic. Included on the map is a peninsula called Kiinaujaq, which means “a face can be seen in the mountain like the face in a coin,” and an island named Ukaliqturliq, or “abundance of arctic hares.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom