Canadians have inherited a tremendous cultural and artistic legacy from the First World War. This is especially so for literature, but also in the visual and performing arts. Although much of this legacy was created during or shortly after the war, the influence of that conflict on culture and art is still felt today and continues to generate new works.

Literature

War literature includes memoirs, diaries and collections of letters, as well as novels and poetry. The first three genres offer direct, personal observations. Ghosts Have Warm Hands (1968) by Will R. Bird, a reissue of And We Go On (1930), has been described as “one of the most powerful memoirs” of the war. In The Great War as I Saw It, Anglican priest and poet Frederick George Scott (1922) provides a moving account of his service as a chaplain in the trenches. The War Diary of Clare Gass, 1915–1918 (2000), edited by Susan Mann, presents a rare first-hand account of a nursing sister’s life in a frontline unit. Other first-hand accounts include Gunner Ferguson’s Diary (1985), which was reissued as Enough Time up the Line (2019) and Letters Home: Maritimers and the Great War, 1914–1918 (2014).

Timothy Findley’s novel The Wars (1977) details the destruction, both mental and physical, of a young Canadian soldier; it is widely considered one of the best war novels ever written. Similarly, Generals Die in Bed (1928) by Charles Yale Harrison depicts the brutal reality of trench warfare. Praised on publication, it is virtually unknown today. It has been compared to the Great War classic, All Quiet on the Western Front (1929) by German author Erich Maria Remarque. Remarque’s “pull-no-punches” novel was probably the first international bestseller and became an award-winning film (1930).

Another celebrated Canadian war novel is Hugh MacLennan’s Barometer Rising (1941), which deals largely with the home front set against the backdrop of the 1917 Halifax Explosion. Joseph Boyden’s Three Day Road (2005) illustrates the experience of Indigenous peoples during the war, both on the front lines and at home. (See also Indigenous Peoples and the World Wars.)

Although not often considered wartime literature, Rilla of Ingleside (1920) by Lucy Maud Montgomery depicts life during the First World War. The novel, the sixth book in the Anne of Green Gables series, focuses on Anne’s daughter Marilla (“Rilla”) and her three brothers, two friends and boyfriend, all of whom serve overseas during the war. It is the only contemporary Canadian novel written about the war from a woman’s perspective.

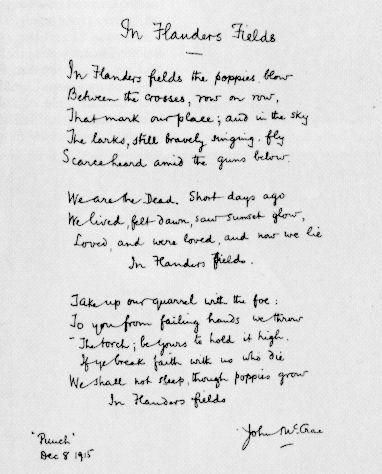

The war also produced many soldier poets. Among the most famous are the British poets Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, Rupert Brooke and Wilfred Owen. Yet the most recognizable poem to come out of the war is Canadian John McCrae’s “ In Flanders Fields,” recited annually at Remembrance Day ceremonies. Almost single-handedly, McCrae’s poem made the poppy an international symbol of remembrance. Canadian poets Robert Service and Edward W. McInnis also served in the war and produced the collections Rhymes of a Red Cross Man (1916) and Poems Written at “the Front” (1918), respectively. (See also The First World War in Canadian Literature.)

Visual Arts

Canada possesses one of the greatest collections of war art in the world, thanks to the War Memorials Fund established in November 1916 by Canadian Sir Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook). The fund commissioned several hundred paintings by Canadian and other artists, including three future members of the Group of Seven. Most of the paintings from this initiative are held by the Canadian War Museum. (See Canadian War Art Programs.)

Yet Canada’s most prolific war artist was not part of Beaverbrook’s programme. Established painter Mary Riter Hamilton applied for a commission to paint at the front lines but was not accepted because female painters were limited to the home front. In March 1919, after the war ended, Hamilton travelled to the Western Front at her own expense and painted the battlefields before they were cleared of war debris. She remained in Europe for three years and created more than 350 paintings of the sites of major Canadian battles. Hamilton’s work is the largest collection of Canadian First World War paintings by a single artist. (See also Canadian Art and the Great War; Documenting the First World War; Representing the Home Front: The Women of the Canadian War Memorials Fund.)

During the war, hundreds of colourful war posters were created both by obscure and known artists. They were used as aids in recruiting, appeals to support the war effort and warnings about the dangers of enemy spies or saboteurs. The posters are an important part of the contemporary visual history of the war. (See also Propaganda in Canada.)

Memorials

The war’s legacy can also be seen in sculpture and architecture. Several war memorials dot the countryside of France and Flanders, including the striking National Vimy Memorial, designed by Walter Allward. Newfoundland’s main memorial is a spectacular caribou statue gazing across the Beaumont-Hamel battlefield where the Newfoundland Regiment was almost destroyed on 1 July 1916.

Ottawa’s National War Memorial features bronze sculptures of 22 men and women representing all the services involved in the First World War. Also in Ottawa, the Valiants Memorial depicts 14 individuals who have played a key role in major Canadian conflicts. Three are from the First World War: Lieut.-Gen. Sir Arthur Currie, Matron Georgina Pope and Cpl. Joseph Kaeble, VC. (See also Monuments of the First and Second World Wars.)

Theatre and Film

Internationally, the First World War has inspired many plays and films. This includes the acclaimed British play War Horse (2007), which was adapted as a film in (2011), and the film 1917 (2019), which has been described as an “unblinking vision of the hell of war.” Canadian playwrights and directors have also responded to the war. Canadian plays include Anne Chislett’s Quiet in the Land (1983) and Wendy Lill’s The Fighting Days (1985). The musical Billy Bishop Goes to War (1978) about the famous fighter ace is one of the most widely produced plays in Canadian theatre. The feature film Passchendaele (2008), written, directed and starring Paul Gross, depicts the experience of Canadian soldier Michael Dunne at the Battle of Passchendaele (also known as the Third Battle of Ypres) and accurately portrays the shocking conditions of trench warfare.

Sheet music cover for “When Your Boy Comes Back to You,” composed by Gordon V. Thompson in 1916.

(Sheet music courtesy of McMaster University Archives & Research Collections)

Music

The First World War also influenced music. Canadians composed thousands of songs during the war, hundreds of which were directly related to the conflict. Two of the most popular were ‘Good Luck to the Boys of the Allies’ by Morris Manley and 'When Your Boy Comes Back to You' by Gordon V. Thompson. (See Canadian Songs of the First World War.) French-language wartime songs include En Avant (1915) by Joseph Vézina. Classical composers Gena Branscombe, Donald Heins and Colin McPhee also wrote patriotic songs during the war. (See Canadian Music from Wars and Armed Conflict.)

Canadian conductor, educator and composer Sir Ernest MacMillan composed his String Quartet in C Minor (1914) while a prisoner-of-war in Germany. Composer Healey Willan wrote the motet How They So Softly Rest (1917) to commemorate members of the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir killed during the war. His anthem In the Name of God We Will Set Up Our Banners (1917) was composed for a military ceremony: the depositing of the colours of the 169th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force in St. Paul’s Anglican Church, Toronto.

On the Western Front, the Canadian Army developed a number of entertainment units, known as “concert parties,” to boost troop morale. One of the most popular was a group of amateur singers known as the Dumbells; after the war, they became a successful vaudeville act. More recently, tenor John McDermott’sreflective renderings of several old and new songsabout the war have received international accolades.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom