Early Years

Barbara Howard was the youngest of five children. Her father, Samuel Howard, was an American immigrant, while her mother, Catherine or “Cassie” (née Scurry), had moved from Winnipeg to Vancouver as a young child. Hiram Thomas Scurry, Barbara’s grandfather, opened a barber shop at 25 Abbott Street in Gastown. According to family lore, when a massive fire ripped through Vancouver in June 1886, Scurry raced down to the harbour at Burrard Inlet with his barber chair on his back, saving it from the fire.

Barbara and her siblings, brother Charles and sisters Melba, Goldvine and Priscilla, grew up at 10th Avenue and Nanaimo in East Vancouver, “on a big hill with a wonderful view.” The family attended the local United Church and was active in the community. After Samuel Howard died in 1929, when Barbara was only eight years old, the family received support from Cassie’s brother, who later helped fund Barbara’s education.

Even as a young child, Barbara was fast, winning the school championship at Laura Secord Elementary School. As a teenager at Britannia High School, she established herself as one of the fastest sprinters in the city. In September 1937, when she was only 17 years old, Barbara took part in the Western Canada British Empire Games trials. She stunned the competition, running 100 yards in only 11.2 seconds (1/10th of a second faster than the British Empire Games record) and beating better known sprinters such as Lillian Palmer and Mary Frizzell. Her performance caught the attention of the national press, with former sprinter Bobbie Rosenfeld of the Globe and Mail rating her one of the “best prospects” for the Games: “Barbara Howard, dusky flash of Vancouver, makes it with me…reports from the coast say she is greased lightning, and her times bear out that fact.” In October, she was named to the Canadian team that would compete at the British Empire Games in Sydney, Australia, in February 1938.

DID YOU KNOW?

In the 1930s, publications often used terms like “dusky” or “coloured” to refer to people with darker complexions, particularly those of African descent.

Media Darling in Sydney, Australia

Howard and her teammates spent 28 days on the ocean liner Aorangi and arrived in Australia in mid-January. On 18 January, The Sydney Morning Herald announced the team’s arrival, singling out Howard in particular.

Dark-eyed and vivacious, Barbara Howard, a strong-looking girl, gives the impression of speed. Like most members of her race, she is a very able sprinter. She is already very popular, and when Mr. J.H. Dunningham, the Minister in charge of the celebrations, jokingly challenged her to a 100-yard sprint, she quickly said, ‘Oh! I’m too young for your class.’ A reply which no one appreciated more than Mr. Dunningham.

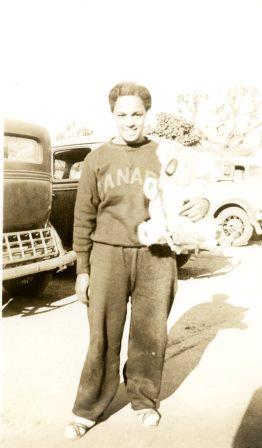

According to the Herald (20 January), “Barbara was a riot wherever she went, and the rush to get her autograph was exceptional,” while Australian Women’s Weekly (27 January) declared the “picturesque” Howard the “[m]ost popular girl in the Canadian team.” Howard received many gifts from her Australian admirers, including a stuffed koala that she still had in her nineties. Even her health made the news, with the Newcastle Sun reporting on 27 January that she “was suddenly stricken with the aches and pains of a sudden and severe cold while training yesterday.”

Back home, Bobbie Rosenfeld commented on the Australian fascination with Howard in “Feminine Sports Reel,” her column in the Globe and Mail. “Barbara Howard, dusky sprinter from B.C., caused quite a stir among Sydney’s popular during her appearance at the Empire games. She apparently was quite a novelty…appearing on the front pages of every newspaper. They seldom see coloured athletes down there…the photographers and autograph seekers kept on her trail.” Howard echoed these remarks decades later. “It was exciting, but I didn’t realize at the time how much of a novelty I was considered. Australia didn’t allow foreigners in then, and because they saw very few Black people they thought I was pretty special.”

On the Podium at the British Empire Games

Overwhelmed by the attention, Howard was not at her best in the 100-yard dash, in which she finished sixth (teammate Jeanette Dolson of Toronto won the bronze). Howard was crushed. “I thought I’d disappointed Canada,” she later recalled. “I was ashamed when I came home that I didn’t have a gold medal.” However, she did win both a silver and a bronze medal at the Games. Howard, Dolson and Aileen Meagher of Halifax took silver in the 440-yard relay and bronze in the 660-yard relay with teammate Violet Montgomery of Winnipeg. One of the top sprinters in Canada, Howard hoped to compete at the next Olympic Games, but the outbreak of the Second World War ended those dreams, as both the 1940 and 1944 Olympic Games were cancelled.

Educator

Howard resumed her education after returning home from the Empire Games. Determined to become a teacher, she attended Normal School for teacher training, with financial support from her uncle. (She later enrolled at the University of British Columbia, graduating with a Bachelor of Education in 1959.) Soon after graduating from the Normal School, Howard got a job teaching at a school in Port Alberni. “I thought I got my first job in Alberni from sending out resumes,” she remarked in 2014. “It never occurred to me that people did not hire Black teachers. About 10 years later, I found out that the principal of the Normal School thought so highly of me for being a hard worker that he went out of his way to get me that first job.”

In 1941, Howard returned to Vancouver, where she found work as a substitute teacher. When she was asked if she would teach a boy’s physical education class at Strathcona School, she agreed. The principal was impressed by her teaching, and she was soon offered a full-time job. Howard was the first racialized person to be hired by the Vancouver School Board.

Howard later taught at Hastings, Henry Hudson and Trafalgar elementary schools. At Trafalgar she taught gifted but underperforming children, many of whom went on to advanced degrees and kept in touch with her. Howard taught for 43 years (14 of those as a physical education teacher), retiring in 1984.

Charity and Community Involvement

As a young teacher in Alberni, Howard became involved in Canadian Girls in Training (CGIT), a program established by the YWCA in conjunction with several Protestant denominations in Canada. In a 2014 interview for Seniors’ Stories, a project of the Vancouver Community Network, Howard recounted her experience volunteering with CGIT, including visits to the Japanese internment camps that were set up during the Second World War.

In 1942, when I must have still been going to Strathcona [elementary school], my church was Grandview Trinity United on Victoria Drive. There was a big Japanese population at the United Church in Richmond, and they used to come to our dances.… When the Japanese were impounded at Hastings Park, our Young People’s Group held dances and entertainment for them at the park. They let us know when they were being sent into the Interior, and we went down to the train to see them off, waving goodbye. I still remember that. Some of them went to Ontario and some to Tashme, a camp they built near Hope.

As a CGIT leader, I went to Tashme to have a CGIT camp with them. The camp was down this long hill, and I could see them running up to the bus to meet me, laughing and waving.… I had to get fingerprinted to get in there and things like that. And, for Thanksgiving, I went back to the camp, and the houses they had there weren’t even lined, they were more like barns. Being Japanese, they had built flower boxes, to bring some beauty to that place, and the RCMP would tear them down. Oh, it was awful!

Howard remained active in the community after retirement, volunteering through the United Church and at Burnaby’s Confederation Centre.

Honours and Awards

- Remarkable Woman Award, Vancouver Park Board (2010)

- Burnaby Sports Hall of Fame (2011)

- BC Sports Hall of Fame (2012)

- Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame (2015)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom