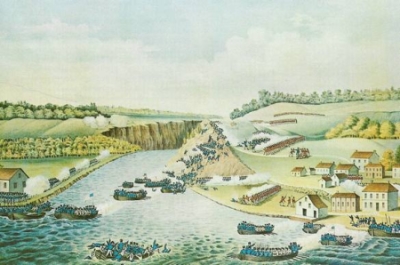

The Battle of Queenston Heights was fought during the War of 1812 on 13 October 1812. One of the most famous battles of the war, the Battle of Queenston Heights was the struggle for a portion of the Niagara escarpment overlooking Queenston, where more than 1,000 American soldiers crossed into Upper Canada. Part of the American force reached the top, circled the British artillery position and forced the British from the Heights. General Isaac Brock, one of the most respected British military leaders of his day, was killed leading a counter-attack. Mohawk chiefs John Norton and John Brant and about 80 Haudenosaunee and Delaware warriors held back the Americans for hours — long enough for reinforcements to arrive so that the British could retain the crucial outpost.

|

Battle of Queenston Heights |

|

|

Date |

13 October 1812 |

|

Location |

|

|

Participants |

Great Britain, Upper Canada militia,

|

|

Casualties |

105 British, militia and First Nations

300 Americans |

Background

The War of 1812 was a conflict between the United States and Great Britain, fought mostly in North America. Lasting from 1812 to 1814, the war was connected to the Napoleonic Wars engulfing Europe at the time.

The Battle of Queenston Heights came in the aftermath of Major General Isaac Brock and Tecumseh’s stunning victory against the US forces at Detroit. The capture of Detroit led US and British authorities to agree to a temporary ceasefire. But instead of bringing peace, the pause allowed both sides to regroup and continue hostilities. The war erupted again at Queenston Heights.

American operations against Upper Canada in the Niagara region (present-day Ontario) were led by General Stephen Van Rensselaer, a militiaman who was one of the wealthiest US citizens. The temporary ceasefire allowed him to marshal his forces and take them on an overland trek from Albany, New York, to Upper Canada.

Situated at Fort George, Brock was guarding the frontier against a US invasion when the ceasefire ended. With 1,500 soldiers and 250 Indigenous allies, he spread his forces, unsure where the next American invasion would occur.

Americans Invade Canada

Stephen Van Rensselaer was under pressure from Washington, and the American public, to reverse the failure and undo the stigma of losing to inferior enemy forces at Detroit. He was also desperate to make something of himself as a field commander. Van Rensselaer chose to cross the Niagara River into Upper Canada at the town of Queenston.

On the night of 12 October 1812, the New York militia launched its invasion across the treacherous Niagara currents. Isaac Brock was convinced they would cross farther down the river at Fort George. The initial attempt at Queenston was also so poorly organized that Brock assumed it was a feint, so he did not consolidate his forces there. This allowed Van Rensselaer to repeat the attempt before dawn on 13 October.

Discovering a hidden path to the top of the escarpment, the Americans were able to seize a British-Canadian redan, or clifftop gun emplacement. The redan’s gun had been hampering the flow of US reinforcements across the river — capturing it gave the US control of the battle.

Death of Isaac Brock

Isaac Brock was awakened by the sound of guns on Vrooman’s Point and along the shore at Fort George. He prepared for battle in haste, as the Americans took command of Queenston Heights. Brock rode his horse hard to Queenston, where he regrouped his forces and personally led a charge to regain the gun the Americans had taken. Sword drawn, Brock charged forward and became an easy target for snipers. He was shot just above his heart and died almost instantly (see Isaac Brock: Fallen Hero).

First Nations Warriors Pin Down the Americans

Isaac Brock’s aide-de-camp, Lieutenant Colonel John MacDonell, was mortally wounded in a similar assault. However, Major General Roger Hale Sheaffe, arriving from Fort George with reinforcements, climbed the heights out of sight of the Americans. These included 300 soldiers and 250 militia. With him were Captain Robert Runchey’s Company of Coloured Men, a regiment of Black men.

Most of the American army had taken position on the heights but became pinned down by a small group of First Nations warriors allied with the British. The actions of Mohawk chiefs John Norton (Teyoninhokarawen) and John Brant (Ahyonwaeghs) and about 80 Haudenosaunee and Delaware warriors were critical at this stage of the battle (see John Norton and the War of 1812).

Norton had made the brilliant tactical decision to climb the escarpment at a considerable distance along the road west of Queenston, an easier climb than the one attempted by Brock closer to the Niagara River. The woods on the right flank of the American

force, moving westward along the heights, provided perfect cover for Norton and his warriors as they pinned down the enemy’s advance until Major-General Sheaffe and his troops arrived (see First Nations and Métis Peoples in the War of 1812).

Attacking from the rear, Sheaffe trapped the enemy between his army and the cliff. Van Rensselaer’s reserves, all from the New York militias and waiting to travel across the river, were called into battle. But upon hearing the roar of the guns they refused to participate, claiming that they were not legally obligated to fight on foreign soil. Denied any ability to renew an attack or bolster his defence, Van Rensselaer’s forces crumbled to a mere 350 regulars and 250 militia, who were running low on ammunition and the will to continue.

DID YOU KNOW?

Runchey’s Company of Coloured Men (named the Coloured Corps) was a militia company of Black men raised during the War of 1812 by Richard Pierpoint, a formerly enslaved man and veteran of the American Revolution. Created in Upper Canada, where enslavement had been limited in 1793, the corps was made up of free and enslaved Black men. Many were veterans of the American Revolution, in which they fought for the British (see Black Loyalists).

American Surrender

Volleys of fire and a British-Canadian charge with bayonets took the American forces by surprise. Alongside the 41st Regiment of Foot and the 49th Foot, Runchey’s Company of Coloured Men “fired a single volley with considerable execution, and then charged with a tremendous tumult,” bringing about the Americans’ surrender.

US Lieutenant Colonel Winfield Scott, taking charge from the wounded commander Captain John Wool, waved a white handkerchief to signal the American surrender. When the smoke had cleared, almost 1,000 Americans were taken prisoner, with 300 killed or wounded, while the victors lost only 28 killed and 77 wounded — including British regulars, Upper Canada militia, Haudenosaunee and Delaware warriors.

One of the British losses was irreplaceable — the much-admired Isaac Brock. But both Brock’s death and the British victory had a fortifying effect on the people of Upper Canada, who had started the war with both doubt and apathy about any possible success against Canada’s mighty southern neighbour and foe.

The British and Canadian forces had earned two victories over the US, but would have to plan their next moves without the aid of Brock’s dynamic, popular and aggressive leadership (see also Battle of Queenston Heights National Historic Site).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom