The Battle of the St. Lawrence was an extension of the larger Battle of the Atlantic— the German campaign during the Second World War to disrupt shipping from North America to the United Kingdom. Between 1942 and 1945, German submarines (U-boats) repeatedly penetrated the waters of the St. Lawrence River and Gulf, sinking 26 ships and killing hundreds. It was the first time since the War of 1812 that naval battles were waged in Canada's inland waters.

Crucial Supply Route

As the war in Europe escalated so did the demand for supplies to support the war effort and the needs of the civilian population in the United Kingdom. Ports along the St. Lawrence River were key to this effort, including Montreal, Trois-Rivières and Québec City. Meanwhile the Nova Scotia ports of Halifax and Sydney became key gathering points for supply convoys heading overseas.

As the Battle of the Atlantic raged, Canadian politicians and naval officials believed it was only a matter of time before German submarines would bring their deadly attacks to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In a speech to the House of Commons on 25 March 1942, Prime Minister William Lyon MacKenzie King said, “Officers of the Canadian naval service (see Royal Canadian Navy) have expressed the view that within a few months submarines may well be found operating within the gulf, and even in the St. Lawrence river. It is known that enemy submarines can leave their bases on the European continent, voyage to the shores of this continent, seek their prey for some days or weeks and return to their bases without the necessity of refueling.”

To help protect shipping in the St. Lawrence, the Navy opened a new base, HMCS Fort Ramsay in Gaspé, Quebec, on 1 May 1942. The base had only one small 18-metre vessel and no aircraft, a presence that just days later would prove wholly inadequate.

First Attacks

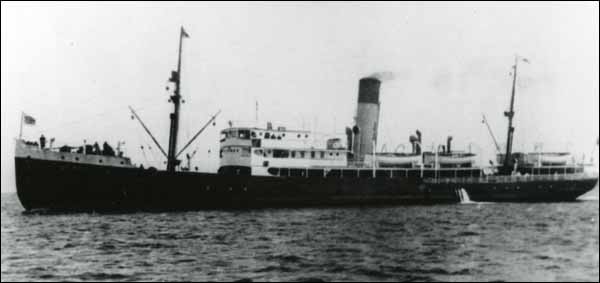

Just days after the opening of the base in Gaspé, the first German submarine, U-553, entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In the late evening hours of 11 May 1942, U-553 attacked its first target off the north shore of the Gaspé Peninsula. The British merchant ship SS Nicoya was en route from Montreal to join a convoy in Halifax, when, at 11:52 p.m., it was struck by a torpedo. Nineteen minutes later, as the crew was evacuating the ship, it was hit by a second torpedo. Six crewmen lost their lives.

Two hours later, U-553 attacked again, firing and striking another freighter, the SS Leto. The vessel sank in mere minutes and 12 of the 43 crew members on board were killed.

Despite knowledge of the U-boat threat, when the attacks happened, they caught the merchant vessels by surprise. One crew member later told the media, “We had no gunners on watch… We never used watches in the St. Lawrence River and we were only due to start them the morning after we were sunk.”

The early response to the first salvos fired in the Battle of the St. Lawrence showed just how unprepared Canadian authorities were. With no planes and only one tiny vessel stationed at the Gaspé base, the minesweeper dispatched to the scene came all the way from Sydney; aircraft were scrambled from Dartmouth, Nova Scotia.

The Navy's Atlantic Coast Command immediately shut down all inbound and outbound traffic on the St. Lawrence. Convoys resumed a few days later with increased naval escorts and additional planes conducting aerial surveillance.

Deadly Shipping Season

The next attacks came seven weeks after the sinking of the SS Leto. In the early morning hours of 6 July 1942, another German sub, U-132, hunted down a convoy of 12 vessels en route from Île du Bic, Quebec to Sydney, Nova Scotia, torpedoing and sinking three vessels.

As the war came close to home, both the media and politicians criticized the government for not doing enough to protect shipping in the St. Lawrence. The mood was especially volatile in Quebec where voters had just overwhelmingly rejected a national plebiscite asking Canadians to release the federal government from its promise not to conscript soldiers for the war effort. Bowing to pressure in Parliament, on 18 July 1942, Prime Minister Mackenzie King held a rare secret session of the House of Commons to privately inform MPs about the campaign against the U-boats.

Shortly afterwards, several naval vessels were diverted from the Atlantic to provide additional protection for convoys in the St. Lawrence. Aircraft support expanded from simply defensive tactics to aggressively hunting submarines, using intelligence to track their movements and to increase support of convoys believed most at risk.

Although these tactics may have reduced the carnage, the submarines continued their deadly campaign. On 6 September 1942, a convoy of eight merchant vessels and five escorts was attacked by U-165 shortly after the convoy left Île du Bic. Two vessels were sunk, including the armed yacht HMCS Raccoon, which was on escort duty. All 38 naval crew on board were killed.

The next day, a different submarine, U-517, struck the convoy, sinking three more freighters and killing 10.

Two days later, on 9 September, the federal government closed the St. Lawrence to overseas shipping. At the time, this was seen as a bitter defeat for the Allies. However, later research by historians indicates the decision was made to divert military resources from the St. Lawrence to the Mediterranean, to support a major, secret Allied offensive planned against the Germans in Europe and North Africa.

The closing of the St. Lawrence to overseas shipping did not clear the area of all marine traffic. Many ships still used the route to supply domestic needs. And on 11 September, HMCS Charlottetown was torpedoed and sunk by U-517 about 11 km off Cap Chat in the St Lawrence River, killing nine crew members. The Flower class corvette had been returning to base after escorting a convoy to Rimouski.

The decline of traffic, however, and the increased aerial patrols had the desired effect. German accounts discovered after the war show that near the end of 1942, German commanders decided not to deploy any more U-boats in the gulf — a decision that remained in effect until the 1944 shipping season.

SS Caribou

The last attack by a German U-boat in 1942 was the deadliest of the Battle of the St. Lawrence. In the early hours of 14 October 1942, U-69 was in the Cabot Strait on its way home from an unsuccessful campaign in the St. Lawrence when it spotted the ferry SS Caribou on a night crossing from North Sydney, Nova Scotia, to Port aux Basques, Newfoundland. On board were 237 passengers and crew.

When the torpedo struck the Caribou, the ferry's lone escort, HMCS Grandmère, following navy directives, went on the attack, trying to ram U-69 and dropping a series of depth charges. However, the U-boat escaped. After two hours, the Grandmère gave up the chase and returned to pick up survivors. The minesweeper rescued 103 people, two of whom later died from exposure.

Although he was following protocol, the decision to delay the search for passengers was a heart-wrenching one for the Grandmère’s captain, Lieutenant James Cuthbert. “Oh my God. I felt the full complement of things you feel at a time like that. Things you had to live with. You are torn. Demoralized. Terribly alone," he later said. "I should have gone on looking for the submarine, but I couldn’t. Not with women and children out there somewhere. I couldn’t do it any more than I could have dropped depth charges among them.”

The list of dead included the Caribou’s captain, Ben Taverner, and his two sons, five pairs of brothers (all crew members), and 10 children.

Did you know?

Nursing Sister Margaret Brooke received an MBE for her heroism after the sinking of the SS Caribou. Brooke and her friend, Nursing Sister Agnes Wilkie, were sucked under the water when the ship went down. They resurfaced and clung to a capsized lifeboat while awaiting rescue. When Wilkie developed hypothermia and lost consciousness, Brooke held onto her friend. Despite her valiant efforts, Wilkie was eventually swept away by a wave.

Spies and Prison Escapes

While U-boats did not attack shipping in the St. Lawrence again until 1944, several did make their way into the Gulf for other reasons.

At 12:30 a.m. on 9 November 1942, U-518 surfaced in the Baie des Chaleurs near the town of New Carlisle, Quebec. Its crew rowed a dinghy ashore, dropping Werner Janowski, a German agent, on Canadian soil. Janowski checked in to the local hotel, immediately raising suspicions. The owners noticed his European clothes and a matchbook from Belgium. When Janowski headed to the train station, they alerted authorities. Janowski was questioned, and he eventually admitted to being a spy. Following an unsuccessful attempt to turn him into a double agent, Janowski was sent to Britain as a resource for British intelligence.

Only two U-boats entered Canadian waters in 1943, and both were part of unsuccessful missions to rescue German prisoners of war (POWs).

In late April, a U-boat was supposed to rendezvous at North Point, PEI, with prisoners from a POW camp near Fredericton, New Brunswick, but the prisoners weren’t able to escape.

The Germans made another attempt in September. This plot involved elite U-boat crews planning to escape from a POW camp in Bowmanville, Ontario. Canadian intelligence discovered the plan when they found documents, cash and fake identification hidden in the bindings of German books delivered to the prisoners by the Red Cross. Despite the advance warning, one prisoner did escape and made it all the way to the rendezvous point at Pointe de Maissonette, New Brunswick, on the Baie des Chaleurs. The escaped prisoner was arrested on the beach. The commander of the rescue U-boat, seeing increased patrols and no waiting prisoners, decided the plan had been foiled and left for home.

Renewed Attacks

By 1944, with plans for D-Day well underway, the Allied demand for supplies increased significantly. Advances in intelligence and communication allowed the Allies to better track German movements in the Atlantic, which meant that Allied supply ships could now sail on their own. Convoys were mustered only when intelligence determined that attacks were possible.

In August, Allied intelligence intercepted messages indicating that U-boats were once again headed to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The military aggressively tracked the submarines with aerial and naval patrols and forced them to remain submerged much of the time, presumably thwarting several attacks.

On the evening of 24 November 1944, U-1228 spotted the Canadian warship HMCS Shawinigan sitting off Port aux Basques, waiting to escort the ferry Burgeo, from Port aux Basques to Sydney the next morning. The U-boat's torpedo caused catastrophic damage. HMCS Shawinigan sank without being able to send a distress signal. All 91 crew members were killed.

Although many consider Shawinigan the last vessel lost in the Battle of the St. Lawrence, another two Canadian warships were sunk by U-boats in Canadian coastal waters. On 24 December, U-806 sank the Bangor-class minesweeper HMCS Clayoquot just outside Halifax harbour. Although most of the men escaped, eight were trapped in the engine room and went down with the ship.

Finally, minesweeper HMCS Esquimalt was sunk on 16 April 1945, only three weeks before the war with Germany ended. The Canadian warship was on antisubmarine patrol when she was torpedoed and sunk about 8 km off Chebucto Head near Halifax by U-190. Forty-four of the ship’s company died, many of them from exposure while waiting to be rescued. Esquimalt was the last Canadian warship lost to enemy action in the war. (See also Sinking of the Esquimalt.)

Memory

The Battle brought enemy forces to Canadian inland waters for the first time since the War of 1812. In the early stages of the campaign, German forces inflicted substantial damage and loss of life. But advances in intelligence-gathering and increasingly effective aerial and naval patrols eventually turned the tide. In the end, more than 440 convoys, numbering some 2,200 ships fulfilled their mission to transport crucial supplies for the war effort overseas.

The bodies of many of those killed were lost at sea forever. Their names and sacrifice are commemorated at the Halifax Memorial in the city's Point Pleasant Park.

In 1999, on the 55th anniversary of the Battle, Governor General Adrienne Clarkson unveiled a Gulf of St. Lawrence Commemorative Distinction to honour the “commendable courage, fortitude and professionalism” displayed by the Canadian and Newfoundland merchant navies.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom