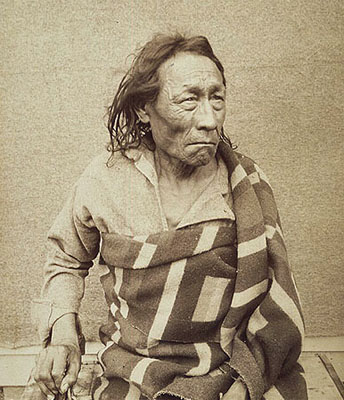

Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear), Plains Cree chief (born near Fort Carlton, SK; died 17 January 1888 on the Little Pine Reserve, SK). Mistahimaskwa is best known for his refusal to sign Treaty 6 in 1876 and for his band’s involvement in violent conflicts associated with the 1885 North-West Resistance.

Early Life

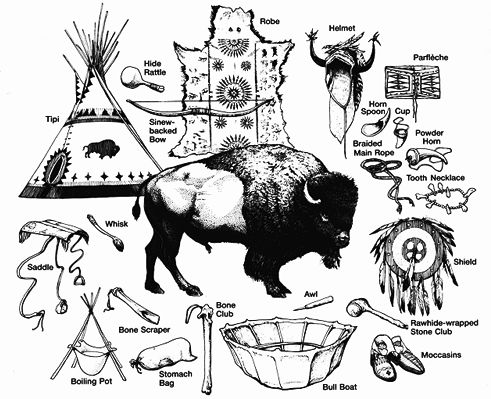

Not much is known about Mistahimaskwa’s early years. His father, Muckitoo (Black Powder), was a minor chief of an Ojibwa-Cree band. Big Bear grew up with Plains Cree bands in Saskatchewan and considered himself Cree. They hunted buffalo in the summer and lived along the North Saskatchewan River in the winter ( see Indigenous People: Plains).

He received his name, Mistahimaskwa, meaning Big Bear, after he had a vision of the Bear Spirit, the most sacred spirit for the Cree. In his power bundle (a sacred and secret bundle that is said to contain protection for the person to whom it belongs), Mistahimaskwa had a bear’s paw, which he wore around his neck during times of danger to provide him with courage and strength.

In 1865, Mistahimaskwa emerged as headman of a small band of Cree people near Fort Pitt, consisting mostly of extended family members.

Battle at Belly River, 1870

In October 1870, Mistahimaskwa and his band took part in a battle between the Plains Cree and their long-standing enemies, the Blackfoot, at Belly River, near Lethbridge, Alberta. It was the last battle fought between First Nations on the Prairies of what is now Canada. The decades following would bring increased White settlement, police and government presence and the disappearance of the buffalo, on which the Cree economy depended.

Leadership, 1870s

Missionaries and traders described Mistahimaskwa as an “independent spirit” who did not like taking direction from outsiders, such as government officials or other Indigenous leaders. For instance, in 1873, Mistahimaskwa disputed with Gabriel Dumont, after Dumont made a suggestion about how to conduct the summer buffalo hunt. In 1874, Mistahimaskwa and his band refused to accept government “presents” of tea and tobacco, which were offered on the Crown’s behalf by Hudson’s Bay Company trader William McKay, who had come to tell the Plains Cree that the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) would be coming to the Plains. Mistahimaskwa believed that these presents were actually bribes, meant to facilitate future treaty negotiations (see Numbered Treaties). Similarly, in 1875, Big Bear was hesitant and dismissive of Reverend George Millward McDougall — the government agent sent to tell the Plains Indigenous peoples that treaty commissioners were coming the following year — telling him, “We want no bait; let your chiefs come like men and talk to us.”

During his visit to the Plains in 1874, McKay reported that Mistahimaskwa was now the chief of a band consisting of about 65 lodges (or 520 people). In comparison, another prominent Cree chief in the area, Wikaskokiseyin (Sweet Grass), only had about 56 followers.

Treaty 6 and Its Impact, 1876–82

In August 1876, lieutenant governor of Manitoba and the North-West Territories, Alexander Morris, went to Fort Carlton to negotiate Treaty 6 with the Indigenous peoples of Saskatchewan. After the treaty had been signed there, Morris and the other commissioners traveled to Fort Pitt in September, near Mistahimaskwa’s home, to gain the adhesions (additional signings) of the Indigenous people there. Mistahimaskwa was away at the time, and therefore, did not attend the negotiations. The treaty was signed in his absence.

When Mistahimaskwa returned home, he was surprised and frustrated that the other chiefs had signed the treaty without consulting him. Although he was concerned with the disappearance of the buffalo and the increasing numbers of European settlers, Big Bear believed that the treaty conditions only seemed to ensure perpetual poverty and the destruction of his people's way of life. Wikaskokiseyin and the other chiefs tried to convince him otherwise, telling him that this was a just and necessary treaty and that his signing it would guarantee economic and other protections for his people. Still, Mistahimaskwa refused to sign the treaty. He compared it to a “rope around our necks”; likely referencing the fact that the treaty would “strangle” their freedom and limit their control over Indigenous land, resources and way of life.

Mistahimaskwa’s defiance attracted independent warriors to his band, and from 1878-79, his influence among the Cree rose. In October 1878, Big Bear and his allies prevented government agents from surveying their unceded land. The surveyors called for the support of the NWMP. According to historian Hugh Dempsey, Colonel Acheson Gosford Irvine threatened arrest if the Cree prevented the surveyors’ work. The Cree complied and the work continued.

The winter of 1879 was particularly difficult for Mistahimaskwa and his people; the disappearance of the buffalo brought terrible hunger. Mistahimaskwa still refused to sign Treaty 6, instead choosing to relocate to Montana, where he and some other Indigenous peoples hunted the last of the buffalo. Upon his return to Canada in 1882, Mistahimaskwa and his band tried to find other food sources, such as fish at Cypress Lake in Saskatchewan, but this was not enough to sustain his band of approximately 250 people. In order to prevent their starvation, Mistahimaskwa signed Treaty 6 on 8 December 1882.

Uniting the Cree, 1882–84

Mistahimaskwa wanted to take a reserve near Fort Pitt, but when he saw the poverty of his friends there, he worked tirelessly — but unsuccessfully — to get further concessions from the federal government. Determined, Big Bear called on Cree chiefs to unite and press the government for one large reserve on the North Saskatchewan River.

In April 1884, Big Bear and his band, which had now grown to about 500 people, began moving toward Battleford, Saskatchewan, where they intended to meet with other Cree peoples to discuss the treaty terms and other matters. On 16 June 1884, approximately 2,000 people gathered at the reserve of Pitikwahanapiwiyin (Poundmaker). Never before had the Cree united politically on such a large scale.

During the council, Mistahimaskwa hosted the Thirst Dance (also known as the Sun Dance) — a ceremony of renewal — which was forbidden by the Indian Act. The dance still proceeded. During the celebration, a young warrior named Kāwīcitwemot physically assaulted the farm instructor of Little Pine reserve, John Craig, after Craig denied the warrior food. The NWMP were called in to respond, and a force of about 90 men arrived at Battleford, ready to arrest Kāwīcitwemot. Although confronted by a group of about 400 armed and angry Cree warriors, the NWMP managed to apprehend Kāwīcitwemot peacefully. To appease the warriors, the NWMP provided large supplies of food. A violent episode that could have potentially trigged a larger battle or war between Indigenous peoples and the police was avoided.

In August 1884, Mistahimaskwa continued to try and unite the Cree, giving speeches to the chiefs at Duck Lake and Fort Carlton about the unfulfilled and unjust terms of Treaty 6. He also spread his message of unity to the Métis, meeting with Louis Riel in Prince Albert.

Mistahimaskwa continued to hold off on selecting a reserve for his people, hoping that a united front would bring better concessions from the federal government. Instead, the government cut off rations to the band, trying to force them into settling. Mistahimaskwa’s band members criticized him for this delay, and it was at this point that his authority began to decline.

Insurrection, 1884–85

As a result of the federal government's refusal to negotiate with Mistahimaskwa, he lost the support of his more extreme followers. By 1885, they had become dominant. Led by Mistahimaskwa’s son Āyimisīs (Little Bad Man) and another warrior, Kapapamahchakwew (Wandering Spirit), the group, commonly referred to as the warrior society, camped along Frog Lake, northwest of Fort Pitt. When news arrived that the Métis had defeated the NWMP at Duck Lake on 26 March 1885 (see Battle of Duck Lake ; North-West Resistance), the warrior society believed that they, too, could successfully take matters into their own hands. On 2 April, they forced all the settlers attending service at the Frog Lake Catholic church outside the building, and Kapapamahchakwew shot Indian agent Thomas Trueman Quinn, who had denied his people food rations. Although Mistahimaskwa tried to stop the violence, the warriors persisted, killing nine men, including two priests. When news of the incident spread, the government considered Mistahimaskwa responsible and an active participant in the North-West Resistance, even though he had lost control of his band at that point.

On 13 April 1885, Āyimisīs, Kapapamahchakwew and 250 of their warriors decided to take Fort Pitt. They issued an ultimatum to the 26 NWMP stationed there to surrender. Mistahimaskwa had warned the NWMP that the warriors were coming. Outnumbered, the police abandoned the fort the next day, leaving behind 44 civilians. The warriors ransacked and burned the fort but did not kill any of the civilians.

On 28 May 1885, Canadian troops attacked Kapapamahchakwew and his men north of Frenchman Butte (see Battle of Frenchman’s Butte). Mistahimaskwa did not participate in the hostilities; he stayed behind with the women, children and captives. The battle ended in a draw; the Cree and the militia withdrew.

On 3 June 1885, Sam Steele’s scouts and other police officers eventually defeated the warrior society at the Battle of Loon Lake (also known as Steele Narrows Battle) — the same battle that ended the North-West Resistance. The Poundmaker First Nation oral tradition maintains that Mistahimaskwa wore his bear claw during the battle to protect him and his people.

After their defeat, the warriors scattered. Kāwīcitwemot was killed by NWMP at Frenchman Butte, Āyimisīs fled to Montana, and Kapapamahchakwew surrendered. In November 1885, six warriors, including Kapapamahchakwew, were hanged for their part in the Frog Lake murders. Mistahimaskwa surrendered at Fort Carlton on 2 July 1885.

Although it is often said that Mistahimaskwa and his people participated in the 1885 North-West Resistance, it is unlikely that the warrior society considered themselves part of a wider strategy to defeat the Canadian government; they pillaged and killed but made no concerted effort to join Pitikwahanapiwiyin or Riel in their attacks at Battleford or Batoche, respectively. Additionally, while Mistahimaskwa was considered a government dissident, he did not participate in the conflict of 1885; rather, he tried his best to bring the violence to an end.

Trial and Sentence, 1885–87

Mistahimaskwa and 14 of his band members were transported to Regina to stand trial. He was tried for treason-felony (i.e. intending to make war against the Queen). Mistahimaskwa was found guilty. Although he had tried to prevent bloodshed and did not participate in the conflict, the presiding judge, Hugh Richardson, argued that Mistahimaskwa should have abandoned his band when they first started to turn violent and mutiny. Mistahimaskwa was sentenced to three years at the Stony Mountain Penitentiary. He converted to Christianity during his imprisonment.

Release and Death, 1887–88

A broken and sick man, Mistahimaskwa only served half of his prison term (one and a half years) and was released in February 1887. According to Dempsey, Mistahimaskwa then travelled to Regina, where he spent a month before going to Little Pine reserve to live with his daughter. It was there that he lived out the rest of his days until 17 January 1888. He was buried in the Roman Catholic cemetery on the reserve.

Legacy

Mistahimaskwa is remembered as a strong and powerful Cree chief and protector of his people. He stood firm against what he considered to be the unjust and inadequate terms of Treaty 6. He also tried to unite the Cree people, so that they could successfully fight against socio-economic injustices as a community.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom