"To be black and female in a society which is both racist and sexist is to be in the unique position of having nowhere to go but up," said Rosemary Brown.

A staunch feminist and a socialist, and Canada’s first Black female member of a provincial legislature, Rosemary Brown battled for equality and human rights in her lifetime. Black women have endured discrimination in Canada — and as seen in this exhibit, much worse — over the course of history. This is but a brief overview of advocates, activists and catalysts for change; those who fought, pushed back and, as Brown said, demonstrated to ensuing generations that there was nowhere to go but up.

Six Black female freedom fighters are featured here: Marie-Joseph Angélique, Chloe Cooley, Harriet Tubman, Mary Ann Shadd, Viola Desmond and Rosemary Brown.

1. Marie-Joseph Angélique

Marie-Joseph Angélique (born circa 1705 in Madeira, Portugal; died 21 June 1734 in Montréal, QC).

Marie-Joseph Angélique was an enslaved Black woman owned by Thérèse de Couagne de Francheville in Montréal. In 1734, she was charged with arson after a fire leveled Montréal’s merchants' quarter. It was alleged that Angélique committed the act while attempting to escape her enslavement. She was convicted, tortured and hanged.

The burning of Montréal, as well as the arrest and subsequent trial of Angélique , reveals much about the nature of enslavement in Canada, a legal institution that existed for over 200 years. It is possible that Angélique did not set the fire. But she made an ideal scapegoat for the crime: she was Black, enslaved, poor, and a foreigner, and so in every aspect was a social outcast. As an enslaved person, Angélique had no rights that New France or white society would respect.

Centuries later, Marie-Joseph Angélique has become a symbol of Black resistance and freedom.

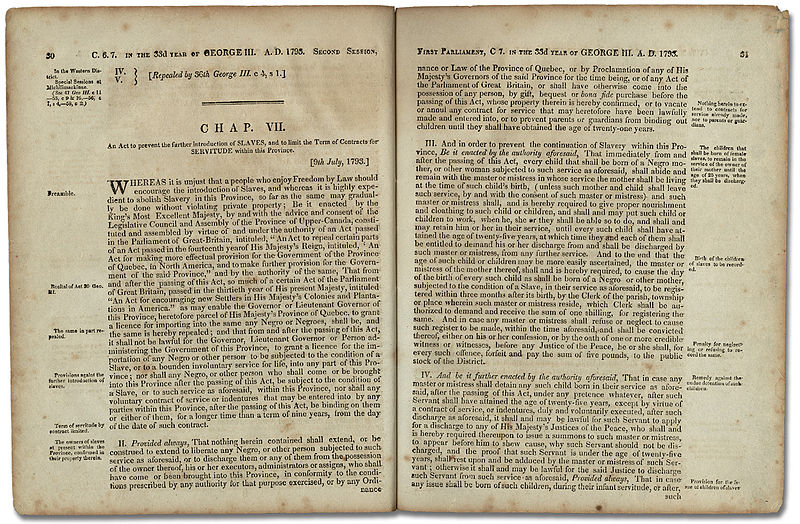

2. Chloe Cooley

Although little is known about Chloe Cooley, an enslaved woman in Upper Canada, her struggles against her “owner,” Sergeant Adam Vrooman, precipitated the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada, 1793 — the first legislation in the British colonies to restrict the slave trade. The Act recognized enslavement as a legal and socially accepted institution. It also prohibited the importation of new slaves into Upper Canada and reflected a growing abolitionist sentiment in British North America.

On 14 March 1793, Vrooman violently bound Cooley in a boat and transported her across the Niagara River to be sold in New York State. Cooley resisted fiercely, causing Vrooman to require the assistance of two other men. The incident was reported to Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe and the Executive Council of Upper Canada. Cooley regularly protested her enslavement by behaving in “an unruly manner”: stealing property entrusted to her on Sergeant Vrooman’s behalf, refusing to work and leaving her master’s property without permission for short periods of time. These strategies were employed by enslaved Africans as a way to disrupt the daily lives of their masters and mistresses, and to resist their forced servitude.

Others employed resistance tactics similar to Chloe Cooley’s. Peggy, an enslaved woman who was owned by Executive Council member and provincial administrator Peter Russell, did the same. She frequently left her master’s property for short periods of time, so much so that Russell had Peggy jailed. In 1803, Russell published a notice in the Upper Canada Gazette warning the public not to harbour Peggy, who absented “herself from his service.” Peggy’s son Jupiter, also owned by Russell, was described by Russell’s sister Elizabeth as defiant, and was also jailed on several occasions. These strategies were employed by enslaved Africans as a way to disrupt the daily lives of their masters and mistresses and to resist their forced servitude.

3. Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman, née Araminta "Minty" Ross, abolitionist, “conductor” of the Underground Railroad (born c. 1820 in Dorchester County, Maryland; died 10 March 1913 in Auburn, New York).

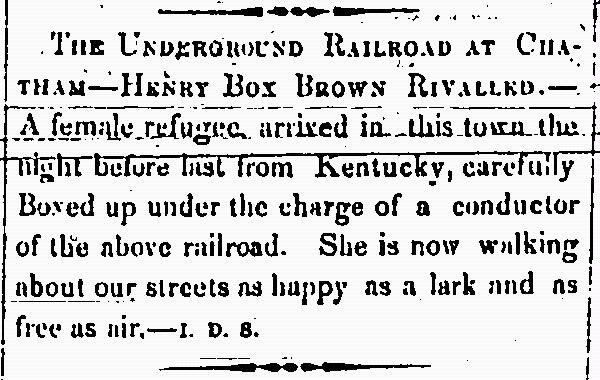

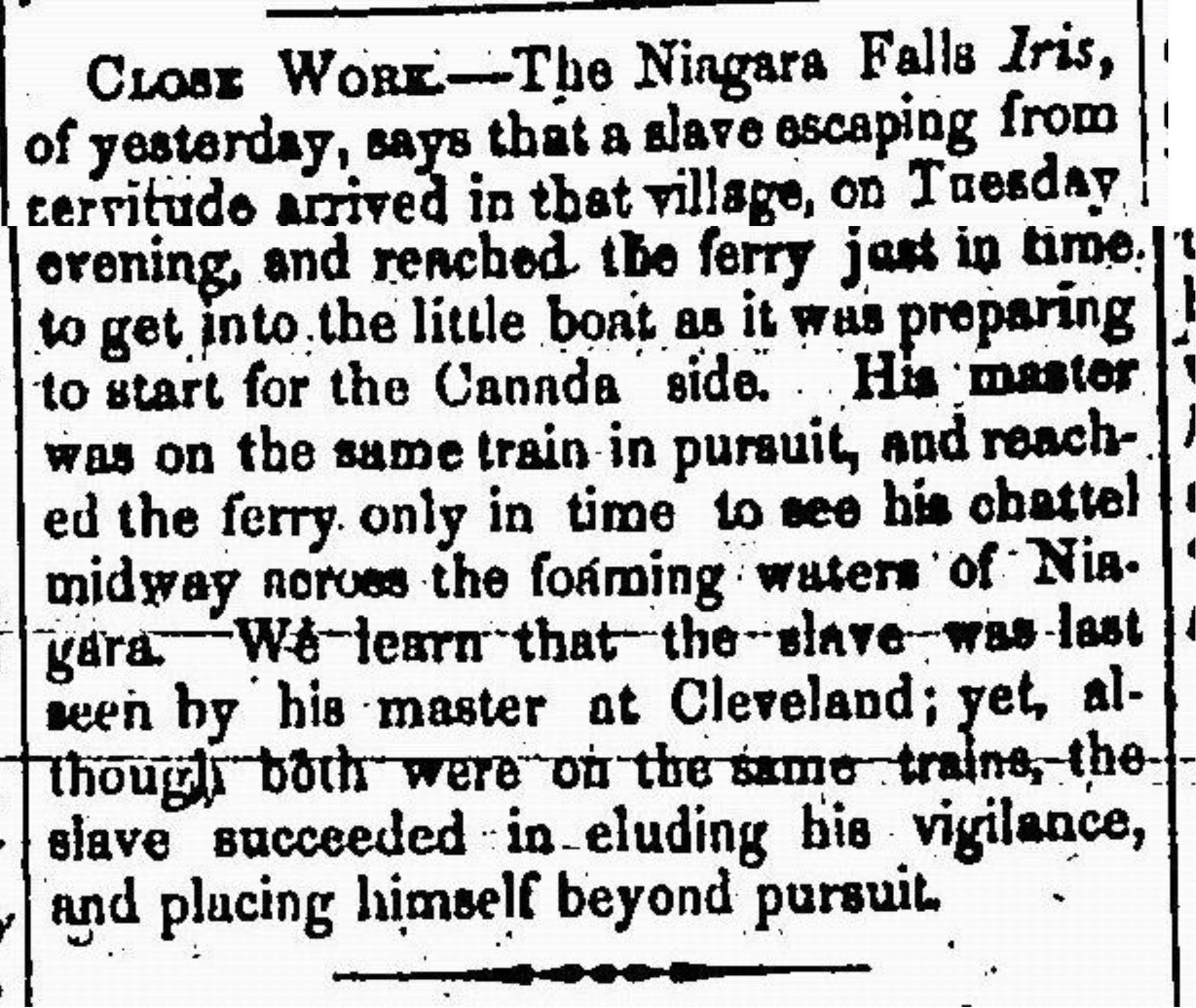

Harriet Tubman escaped from enslavement in the southern United States and went on to become a leading abolitionist before the American Civil War. She led numerous enslaved persons to freedom in the “free” Northern states and Canada through the Underground Railroad — a secret network of routes and safe houses that helped people escape enslavement.

Tubman resided in St. Catharines, Canada West (Ontario), between 1851 and 1861 for varying periods of time while she continued her rescue missions in Maryland. In 1858, she met John Brown, the revolutionary leader of the attack on Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia. In an effort to support his plan to lead a rebellion against enslavement in the American south, Tubman hosted a meeting at her home to find recruits for Brown and to share information that would be useful to his plot. Brown wanted “General Tubman” to accompany him in the uprising, but her health condition prevented her from joining him.

Tubman devoted her life to serving others and fighting for freedom and equality. Tubman’s activism extended beyond her daring missions to guide escaping slaves to freedom. She travelled in the United States to speak out against enslavement and fought for universal suffrage. In honour of her courage, humanitarian efforts, heroism, and her life of service, 10 March was declared Harriet Tubman Day in the US, as well as in St. Catharines, in 1990. In 2005, she was designated a Person of National Significance by the Government of Canada. She remains a notable international icon of freedom.

"I wouldn't trust Uncle Sam with my people no longer, but I brought 'em clear off to Canada" — Harriet Tubman

4. Mary Ann Shadd

Mary Ann Camberton Shadd Cary, educator, publisher, abolitionist (born 9 October 1823 in Wilmington, Delaware; died 5 June 1893 in Washington, DC).

The first Black female newspaper publisher in Canada, Mary Ann Shadd founded and edited The Provincial Freeman. Shadd also established a racially integrated school for Black refugees in Windsor, Canada West. In 1994, she was designated a Person of National Historic Significance in Canada.

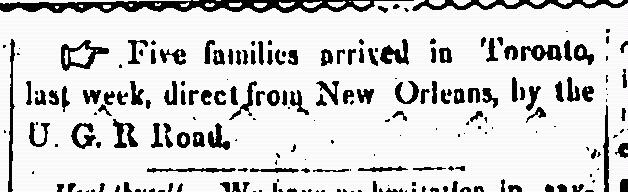

An estimated 30,000 to 40,000 freedom-seekers — born free or enslaved — reached Canada through the Underground Railroad. To promote emigration to Canada, Shadd publicized the successes of Black persons living in freedom in Canada through The Provincial Freeman, a weekly newspaper first printed on 24 March 1853. “Self-Reliance Is the True Road to Independence” was the paper’s motto.

The newspaper was co-edited by Samuel Ringgold Ward, a well-known public speaker and escaped enslaved person living in Toronto. While Ward was listed as editor on the paper’s masthead, Shadd did not list her own name, thus concealing the paper’s female editorship.

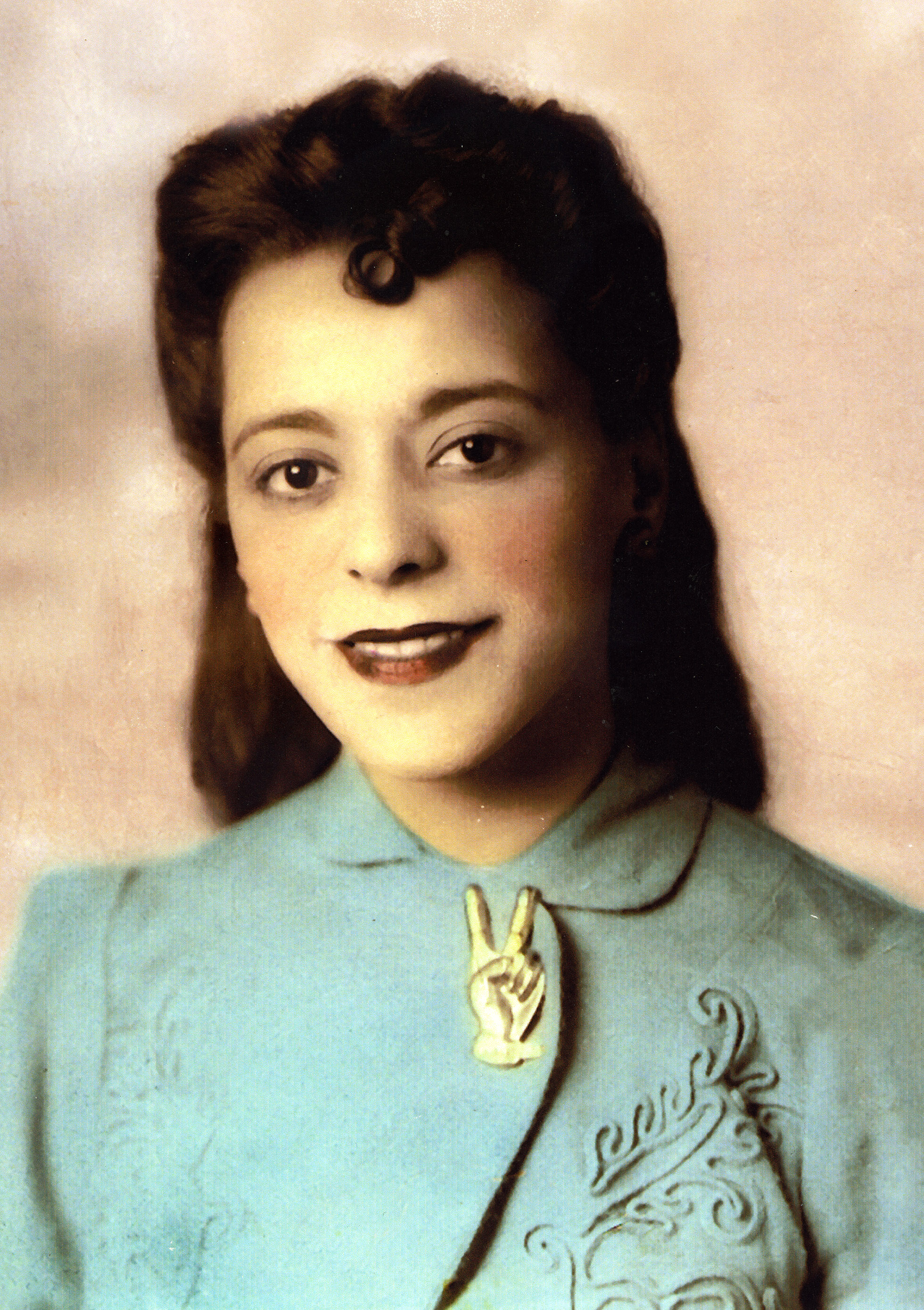

5. Viola Desmond

Viola Irene Desmond (née Davis), businesswoman, civil libertarian (born 6 July 1914 in Halifax, NS; died 7 February 1965 in New York, NY).

Viola Desmond built a career as a beautician and was a mentor to young Black women in Nova Scotia through her Desmond School of Beauty Culture. It is, however, the story of her courageous refusal to accept an act of racial discrimination that provided inspiration to a later generation of Black persons in Nova Scotia and in the rest of Canada.

On the evening of 8 November 1946, Viola Desmond stopped in the small community of New Glasgow, NS, after her car broke down. She decided to see a movie to pass the time. At the Roseland Theatre, Desmond requested a ticket for a seat on the main floor. The cashier refused, saying, “I'm sorry but I'm not permitted to sell downstairs tickets to you people.” Realizing that the cashier was referring to the colour of her skin, Desmond decided to take a seat on the main floor.

Desmond was arrested for sitting in the “Whites Only” section of the theatre. She fought her conviction of defrauding the government of the difference in tax — one cent — between tickets in the racially-separated sections. Though the conviction was upheld, her struggle became a catalyst for change. In 2010, Desmond was pardoned by Nova Scotia Lieutenant-Governor Mayann Francis.

6. Rosemary Brown

Rosemary Brown, née Wedderburn, OC, OBC, social worker, politician (born 17 June 1930 in Kingston, Jamaica; died 26 April 2003 in Vancouver, BC).

Rosemary Brown has the distinction of being Canada's first Black female member of a provincial legislature and the first woman to run for leadership of a federal political party.

During the turbulence of the 1960s, Brown found renewed purpose in her role as a political advocate against both racism and sexism. At the time, traditional roles of race and gender were being challenged in Canadian politics. She brought a level of awareness to her role as Ombudswoman and founding member of the Vancouver Status of Women Council. ( See also Council on the Status of Women.)

On 30 August 1972, Brown was elected to the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia. During her 14 years as MLA for the NDP, Brown created a committee to remove sexism in British Columbia's educational material and was instrumental in the formation of the Berger Commission on the Family, among her many other accomplishments. During that time, she also ran for leadership of the federal NDP in 1975. With the slogan "Brown is Beautiful," she broke colour barriers in the federal arena when she ran a close second to Ed Broadbent, ahead of three other candidates.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom