When the First World War began in August 1914, the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) was unprepared to fight a war at sea. Founded only in 1910, it consisted of two obsolete cruisers, HMCS Niobe and HMCS Rainbow, and about 350 regular sailors, augmented by 250 reservists. During the war, it was assigned a growing number of tasks, which it was ill-equipped to perform. This included protecting Canadian coastal waters against German U-boats. The RCN scrambled to find ships and sailors but was ill-equipped to fight enemy submarines, which sank several vessels in Canadian waters in 1918.

Background

In 1910, the Naval Service Act was passed; the Act established the Canadian navy and allowed the purchase of HMCS Niobe and HMCS Rainbow. The following year, Robert Borden’s Conservatives won the general election and slashed the RCN’s budget. When the First World War began, the RCN scrambled to obtain ships, borrowing vessels from other government departments and chartering others from commercial firms. Several wealthy Canadians also donated, loaned or sold (at nominal prices) their private yachts to the navy.

Even with these vessels, the navy was only capable of limited tasks. It examined merchant ships entering Halifax harbour, swept harbour approaches for mines and carried out occasional antisubmarine patrols along the Nova Scotia coast.

In the fall of 1914, Prime Minister Robert Borden asked the British Admiralty what naval aid Canada could provide to Britain. The reply from First Sea Lord Winston Churchill was not encouraging: “Admiralty inform don’t think anything effectual can now be done as ships take too long to build and advise Canadian assistance be concentrated on army.”

In November 1914, Borden asked the Admiralty for new destroyers and submarines, which would be constructed in Canada. He also asked to borrow ships from the Royal Navy (RN) until they were built. But Britain had no ships to lend.

Unrestricted Submarine Campaign, 1915

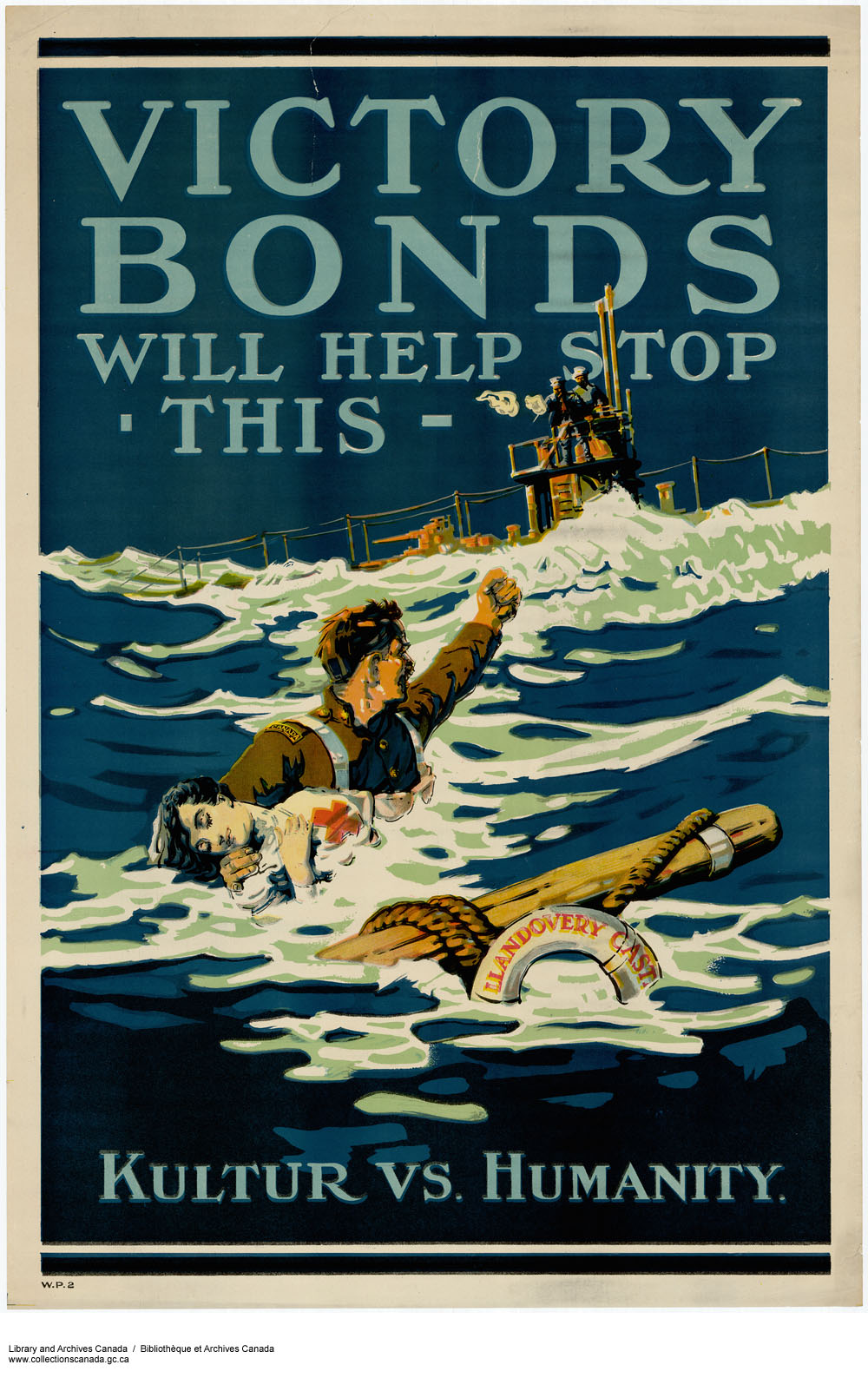

On 1 February 1915, Germany launched an unrestricted submarine campaign against all merchant vessels, including neutrals, found in British waters. (See U-boat operations.) After the passenger liner Lusitania was torpedoed off the Irish coast on 7 May, the Admiralty warned that U-boats might begin operating soon in the northwest Atlantic and suggested Canada establish antisubmarine coastal patrols.

RCN Response

The RCN did not, however, have enough ships to establish antisubmarine patrols. It purchased additional private yachts and armed them with torpedo tubes and 3- and 6-pounder guns, plus the odd 12-pounder. By 1 September 1915, the RCN had enough small ships to patrol the Nova Scotia coasts, protect Halifax harbour and set up a Gulf of St. Lawrence patrol. At the same time, Germany ended its unrestricted submarine campaign, which had been condemned by other nations.

In November 1916, the Admiralty advised the RCN to increase its east coast antisubmarine patrol to 36 vessels mounting 12-pounder guns. The navy ordered 12 trawler-type minesweepers in Canada, while the Admiralty ordered another 24. The head of the Canadian Naval Service appointed Acting Captain Walter Hose to command the east coast patrols. Due to conflicting chains of command between Britain and Canada and uncertainty over various responsibilities, Hose faced a difficult task.

Renewed U-Boat Threat, 1917–18

On 1 February 1917, Germany again proclaimed an unrestricted U-boat campaign. In response, the British finally instituted a convoy system for transatlantic shipping. But the success of the convoys led the Admiralty to believe that U-boats would cross the Atlantic in search of easier targets. In response, the RCN ordered another 12 minesweeping antisubmarine steel trawlers in the spring of 1917. Each 40-metre, 350-ton vessel had a crew of 18 and mounted a 12-pounder gun.

The British also suggested naval air patrols, but Canada did not possess naval aircraft. As a stopgap measure, two US naval air stations were established in Nova Scotia in August 1918 while recruiting began for a Royal Canadian Naval Air Service the same month. Meanwhile, the Admiralty ordered another 36 trawlers and 100 drifters from Canadian shipyards, to be manned by the RCN.

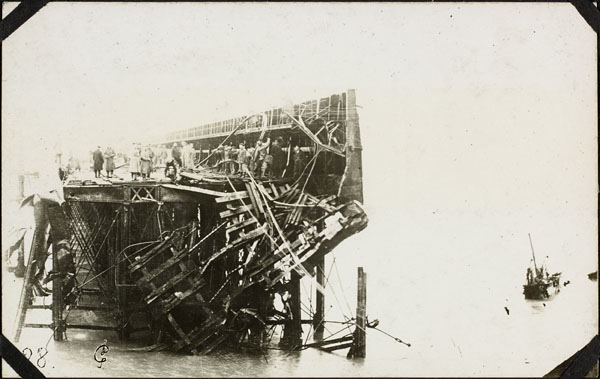

In May 1918, U-boats appeared in American waters before moving to Canada. On August 2, U-156 set the schooner Dornfontein ablaze in the Bay of Fundy. Seven more schooners were sunk along the Nova Scotia coasts during the next two days, followed by three fishing boats. Early on the morning of August 5, U-156 torpedoed the British tanker Luz Blanca 55 kilometres south of Halifax before escaping to the south.

U-156 returned to Nova Scotia and patrolled off Cape Breton Island. It captured the motorized trawler Triumph and turned it into a mini-raider mounting a gun. Triumph sank six schooners before its crew scuttled it after running out of coal. On August 25, U-156 sank another trawler and then captured four schooners. As the U-boat started to destroy the schooners, a four-ship RCN flotilla appeared. U-156 quickly submerged and got away. German submarines sank an additional six vessels before U-156 departed Canadian waters for Germany in September 1918; it was sunk by a mine off Scotland en route. U-155 continued to operate off Nova Scotia, laying minefields along the Nova Scotia coast before sinking a trawler.

Canadians were outraged, but there was little the navy could do. The RCN had only 11 vessels on the east coast, five of which could venture beyond coastal waters. The navy acquired three more ships from other government departments and seven wooden trawlers from American sources.

Assessment

Overall, the convoy system was the most effective antisubmarine measure in the open ocean, while antisubmarine vessels concentrated on coastal waters. Several ships were sunk by German U-boats in Canadian waters, but the vast majority were fishing vessels, which did not affect the war effort.

During the war, the fledgling RCN had been assigned tasks that were beyond its capabilities. Its ships were too few and too small, as well as being undergunned and underequipped. The navy didn’t have enough sailors to fully staff its ships, and many of its personnel were not trained or experienced enough to conduct antisubmarine warfare. The Royal Canadian Naval Air Service, established in September 1918, never saw active service.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom