“All these European troubles are not worth the bones of a Toronto grenadier,” claimed the University of Toronto history professor and Great War veteran Frank Underhill in 1935. Another war seemed to be coming in Europe, and Canadians, far from the conflict, would face a difficult choice of whether to stand again with Britain or remain isolated and safe in North America.

Germany Threatens Europe

The German dictator and Nazi leader, Adolf Hitler, in power since 1933, signalled the return of Germany to a position of strength in Europe. Hitler’s frenzied speeches about restoring honour after Germany's defeat in the First World War and the humiliation of the Treaty of Versailles, and his orders to engage in a program of rearmament, put the 'fatherland' on a new course for war. His totalitarian regime spread terror by assassinating political rivals, putting his enemies into concentration camps and persecuting Jews. Hitler cajoled and lied, oscillating between aggression and conciliation to confuse his enemies, but always with a goal of guiding Germany to its full might through war.

Canadians wanted nothing to do with another war in Europe, and neither did France and Britain, both desperately seeking to placate Hitler through negotiations and appeasement. In Ottawa, the Liberal government of William Lyon Mackenzie King hoped to steer Canada along a path of neutrality. However, the wily prime minister also knew that English Canadians would never agree to let Britain fight Germany alone without support from Canada and the other dominions.

King, too, had pledged support to Britain as far back as 1923. "If a great and clear call of duty comes, Canada will respond, whether or not the United States responds, as she did in 1914,” King had said – although he feared such public pronouncements upon his return to power in 1935 would alienate Québec. French Canadians, who were far more isolationist than the rest of Canada, had no strong ties to Britain and associated war with the conscription crisis that had damaged English–French relations during the Great War. In King’s mind, even preparation for the coming war was to be avoided for the sake of unity in Canada and for the sake of his Liberal Party, which had its power base in Québec. But there was no way to avoid the escalating violence in Europe.

Fascist Aggression

The Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was, like Hitler, anxious to expand his influence at the expense of weaker nations. Aching to avenge a defeat inflicted by the Ethiopians in 1896, Italian forces invaded the poor African country of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in late 1935. The League of Nations, an international body set up after the Great War to promote peace and punish aggressors, protested the action, but it had no teeth and little backbone.

Canada played a small part in the debacle. The head of its League delegation, Walter A. Riddell, on his own accord and in the absence of clear instruction from Ottawa, proposed Western sanctions against Italy. Mussolini feared economic sanctions, especially the blocking of oil, iron and coal imports, that would hurt his ability to wage war. However, the newly formed King government, which had come to power at this time in a landslide electoral victory, rejected the sanctions. Canada looked timid as it slunk from any responsibility in European affairs. While this was a low point in Canadian diplomacy, King believed, rightly, that no Canadian would go to war over Ethiopia. The British and French agreed, indicating that they, too, were unwilling to shed blood in defence of Ethiopia's liberty. Mussolini bullied his way to conquest.

The dictators were emboldened by the League of Nation’s impotency. In March the next year, Hitler brazenly reoccupied the Rhineland, which was a demilitarized zone decreed by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles to act as a buffer with France. Britain and France protested the move but kept their sabres sheathed. Their weak response confirmed in Hitler’s mind that the West lacked willpower to act. He did not. Hitler ordered increased rearmament in direct contravention of the Treaty of Versailles.

In the summer of 1936, the Spanish Civil War erupted, tearing that country apart for three long years. While the West pleaded neutrality, Hitler and Mussolini poured money, weapons and soldiers into Spain to support the nationalist armies of the fascist dictator Franco. About 1,500 Canadians fought in the civil war on the side of the Communists, even as the King government passed the Foreign Enlistment Act that effectively forbade individual Canadians serving with the forces fighting in Spain. The King government did little to enforce the law, although the RCMP spied on potential recruits seeking to leave, and on veterans of the conflict when they returned to the country.

As the war there claimed the lives of tens of thousands of civilians and soldiers, the West again did little to stand up to the dictators. Europeans shivered at the looming prospect of a seemingly unavoidable wider war. All nations began to rearm.

Appeasement

Hitler seemed insatiable, but perhaps a wily and skilled mediator might lead him along the road to peace. King thought he was that man. Seeking to avoid war at any cost, King travelled to Berlin to see the dictator, even as he was warned by advisors to be wary of Hitler’s charms. Meeting on 29 June 1937, King nearly swooned at the attention from Hitler, whom King saw was a fellow mystic and who professed to be a man of peace. King was not the last politician to be tricked by the Nazi leader, whose endgame was war and conquest.

After Germany reoccupied the Rhineland, King’s frank comment in the House of Commons was that Canada would not be dragged into war: "The attitude of the government is to do nothing." Such cautious action brought little glory to Canada, but few wanted war and the military forces were decrepit. King and his two chief advisors, Under-secretary of State for External Affairs O.D. Skelton and Minister of Justice Ernest Lapointe, cautioned the prime minister that Canada’s fragile unity might not survive another unfettered war effort. King took their advice, although he felt that English Canada would demand that the country stand with Britain.

Since the end of the First World War, the Canadian defence budget had been pitifully low, and it had been further ravaged during the Great Depression. King had no desire to rearm Canada. However, as Europe militarized, he allowed the Royal Canadian Navy to replace its obsolete warships with a handful of modern destroyers that he claimed were for home defence.

King and Roosevelt

As Europe spiralled downward towards war, King strengthened economic bonds with the United States in favourable trade deals, first in 1935 and, again, in 1938. Here he was guided by Skelton, who sought to move Canada away from the tight control of Britain and embrace, in his words, a “North American mind.” This was no easy thing, and it would require a gradual shift of English-Canadian hearts more than minds.

King also developed a close relationship with Franklin Roosevelt. The American president liked Canada (he had a summer home on Campobello Island in New Brunswick), but he also worried about Canada’s weak armed forces. Roosevelt’s military advisors told him that their northern neighbour would not be able to withstand an invasion from Germany or Japan, which was showing increased aggression to the West after its war with China in 1937.

On 18 August 1938, Roosevelt was in Kingston, Ontario, to receive an honorary doctorate from Queen's University. He used the occasion to tell Canadians that the two democracies stood shoulder to shoulder, and the United States would never allow any threat to Canada. Canadian commentators were pleased at the pledge, but King also worried that any defence of Canada against an invading force would involve, in turn, an American force on Canadian soil. King ordered more money for rearmament.

As Canada purchased new planes for the dilapidated Royal Canadian Air Force and devoted funds for coastal defences, King sold this spending to wary Canadians as necessary for home defence rather than for sending an expeditionary force overseas. That placated some in Canada, but Britain was left hanging. London inquired, with growing urgency, about whether Canada would support it in what seemed an increasingly unavoidable war. King remained coy, refusing to provide affirmation in order to provide himself with wiggle room and not spook French Canadians.

Crisis Worsens

When Hitler annexed Austria in March 1938, the West made more excuses and still strove for peace. Half a year later, as Hitler threatened to march his armies on Czechoslovakia, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain sought to appease Hitler, signing the Munich Agreement in September. With this pact, he sold out the people of democratic Czechoslovakia by offering Hitler the Sudetenland, a border region of Czechoslovakia with a large German population. King backed Chamberlain’s appeasement policy, hoping it would avoid war. For a time, it seemed to. King was as shocked as everyone when Hitler brazenly occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia on 15 March 1939. War seemed inevitable.

King despaired at the prospect of another overseas bloodbath dragging Canada into conflict. Nonetheless, he wrote in September 1938 that “it was a self-evident national duty, if Britain entered war, that Canada should regard herself as part of the British empire.” An historic Royal visit by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in the spring of 1939 was a monumental success in reaffirming the bonds between Canada and Britain. King revelled in the royals' popularity that saw them greeted by crowds numbering in the tens of thousands wherever they went.

But King and much of his Cabinet remained fearful of publicly committing Canada to any position, especially one that would alienate people in Québec. King unhelpfully refused to let RCAF officers begin discussions with Britain’s Royal Air Force in matters of training. The army, too, continued to be starved of resources.

Going to War

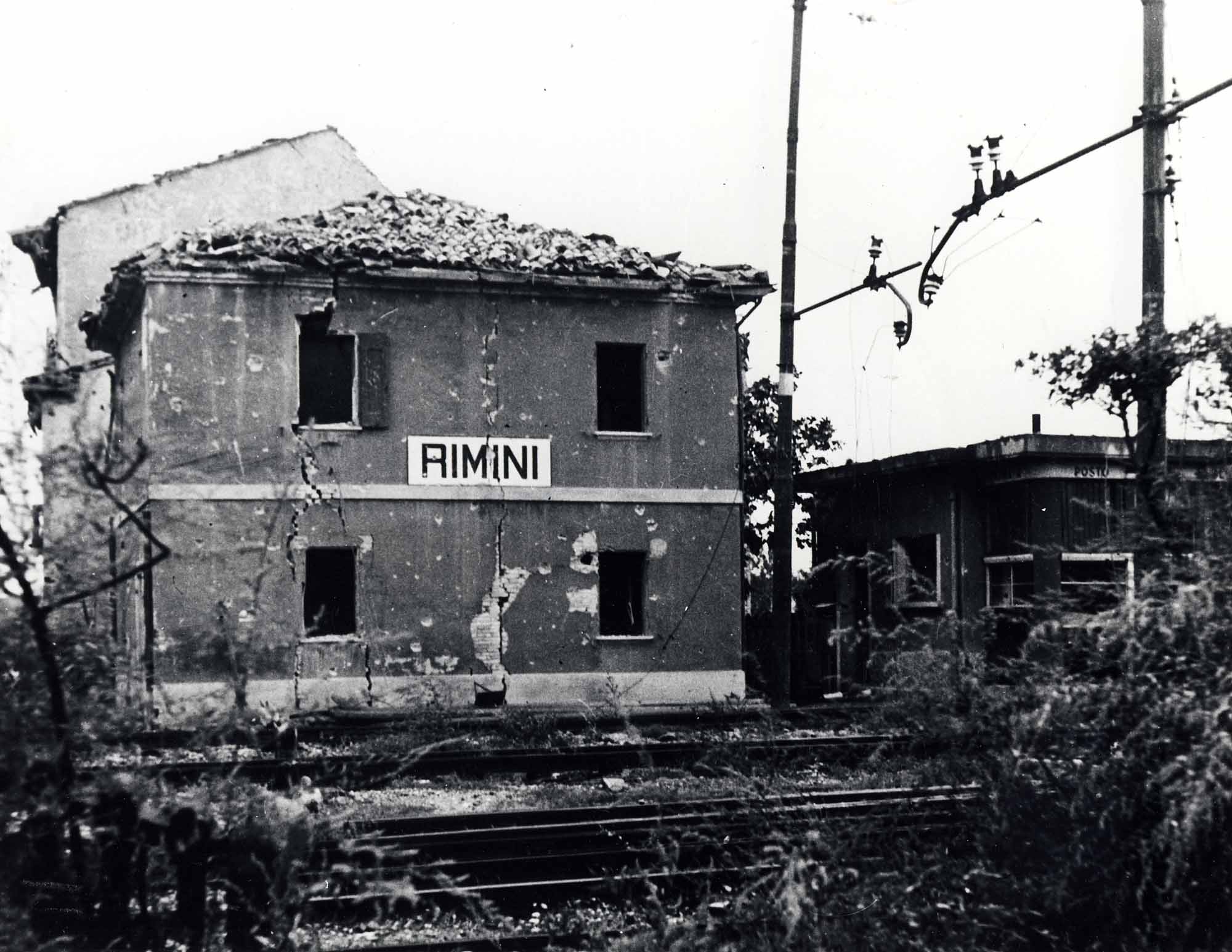

Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939. The governments of Britain and France now felt they had no other choice but to stand up to Hitler, and they declared war on 3 September. Britain hoped its dominions would flock to the colours. Newfoundland, then a British colony and not part of Canada, was automatically at war, and the conflict would have a tremendous impact on the islanders. Newfoundland became a forward-operating base for Americans and Canadians in the Battle of the Atlantic. St. John’s was a crucial port for sailors and airmen.

With Britain’s declaration of war, King was worried how Quebecers would respond, and he announced in a nationwide radio broadcast that “Parliament will decide.” Starting on 7 September, members of Parliament debated the merits of war. The speeches were overwhelmingly in favour of supporting Britain. Almost no one mentioned or cared about the persecution of the Jews under Hitler’s draconian regime, although the war was framed as a just one for democratic values. The Québec wing of the Liberal Party remained suspicious. King’s speech to the House of Commons — at a time when political speeches in Parliament still mattered — was long, boring and dreadful. It did little to inspire the nation. He was saved by his Québec lieutenant, Ernest Lapointe, who spoke passionately about supporting Britain and France in a war against Nazi aggression but who also promised there would be no conscription. Save for pacifist J.S. Woodsworth, who pleaded for Canada to stay out of the war, the House was nearly unanimous. The vote was cast on 10 September. Canada chose to go to war against Germany.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom