Hong Kong was the first place Canadians fought a land battle in the Second World War. From 8 to 25 December 1941, almost 2,000 troops from Winnipeg and Quebec City — sent to Hong Kong expecting little more than guard duty — fought bravely against the overwhelming power of an invading Japanese force. When the British colony surrendered on Christmas Day, 290 Canadians had been killed in the fighting. Another 264 would die over the next four years, amid the inhumane conditions of Japanese prisoner-of-war camps.

|

Battle of Hong Kong |

|

|

Date |

8–25 December 1941 |

|

Location |

Hong Kong

|

|

Participants |

United Kingdom, India, Hong Kong, China, Canada; Japan |

|

Casualties |

783 Canadians (including 290 killed*) *another 264 died in Japanese POW camps |

Why Canadian Troops Went to Hong Kong

Canada entered the Second World War against Germany in 1939, but the Canadian Army saw little action in the early years of the conflict. For one thing, Canada’s military was small and unprepared for war. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was also cautious about committing the country to battle. After the heavy bloodletting and the domestic divisions of the First World War, King was wary of sending large numbers of soldiers to fight overseas — something that might require conscription and re-ignite conflict between French- and English-speaking Canadians. Instead, King sought other ways for Canada to help the war effort, such as making armaments, growing food and training air crews under the new British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. (See Mackenzie King and the War Effort.)

The Royal Canadian Navy had been involved in the Battle of the Atlantic since 1939, and Canadian airmen had made a small contribution to the Battle of Britain, but the Army was not actively engaged in the war — despite growing pressure among English Canadians for a greater role. So in 1941, when Britain made a request for Canadian troops to help bolster its remote Asian colony of Hong Kong, the King government agreed to send two battalions overseas, for what it assumed would merely be garrison duty.

Hong Kong in November 1941

Japan had been waging war in China since 1937, but it had avoided open hostilities against the West. By 1940, the British were fighting for survival against Germany. They realized that defending Hong Kong would be virtually impossible if the colony, and other Asian possessions, were attacked by Japan. Even so, Britain decided that a show of force might deter any possible Japanese aggression, and it sought troops to reinforce the British and Indian units already garrisoned in Hong Kong.

The King government agreed to dispatch two battalions. Harry Crerar, chief of the general staff, assigned the task to the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the Royal Rifles of Canada (from Quebec City). Both units had some experience serving on garrison duty; however, neither was at full strength in 1941, or adequately trained for the modern warfare of the time. Neither regiment had even participated in battalion-level training exercises. No matter — a Japanese attack against British territories in the Pacific seemed unlikely. Even if one came, the prevailing racial attitudes of the time convinced many Canadian and British military leaders that superior White troops would teach the Japanese a lesson.

The two undermanned Canadian battalions were quickly filled out with additions of new, inexperienced troops and shipped across the Pacific, under the command of Brigadier J.K. Lawson. The force included 1,973 officers and men plus two nursing sisters. It arrived in Hong Kong on 16 November, joining a military garrison that now totalled about 14,000.

The garrison’s task was to defend a small, hill-capped colony of 1.6 million residents spread across a section of the mainland including the New Territories and Kowloon, as well as Hong Kong island itself. The defenders had only a few naval vessels at their disposal and no air force to speak of. To make matters worse, the Canadian contingent’s vehicles, sent across the Pacific on a separate ship from the troops, arrived not in Hong Kong but in Manila, where they had been diverted for use by American forces.

On 7 December — three weeks after the Canadians arrived in Hong Kong and had begun to settle into the quiet routines of garrison life — Japan stunned the world by attacking the United States’ naval fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Suddenly, the whole Pacific theatre, once an afterthought in the early years of the Second World War, was now at the very forefront of the conflict.

DID YOU KNOW?

Adrienne Clarkson, Canada’s 26th governor general, was born in Hong Kong in 1939. Her father, William Poy, was a prominent businessman who lost his property after the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong. Clarkson arrived in Canada with her parents and older brother, Neville, as refugees in 1942. At the time, the Chinese Immigration Act excluded the arrival of virtually all Chinese immigrants. However, William Poy’s work at the Canadian Trade Commission in Hong Kong is believed to have helped him bring his family to Canada under “special circumstances” granted by the government.

Invasion and Defence of Hong Kong

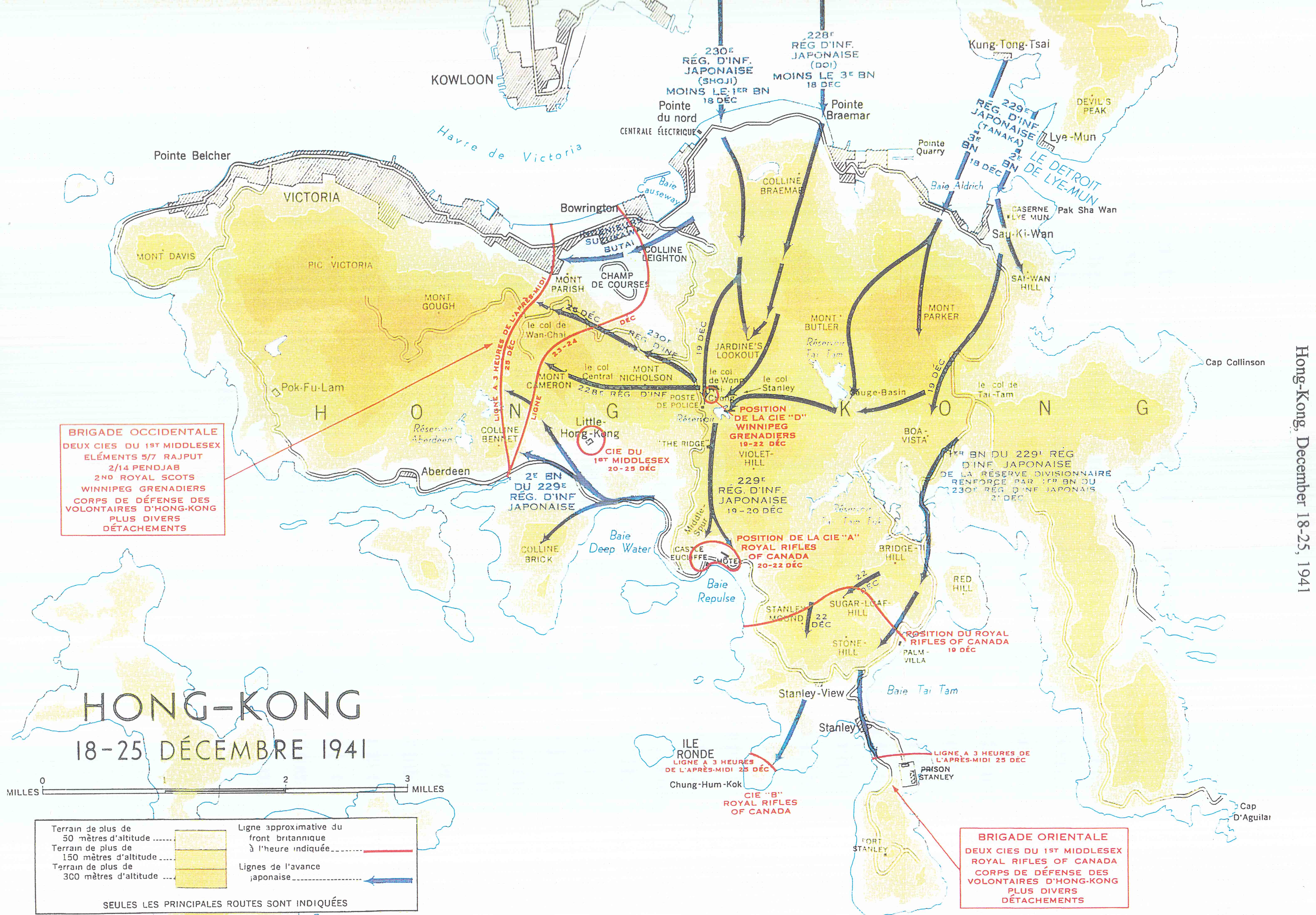

Six hours after the bombing at Pearl Harbor, the Japanese 38th Division — made up of well-trained, battle-hardened troops — attacked Hong Kong. The invaders bombed the colony’s airfield and other military installations and quickly overran the troops defending the mainland portion of the territory. The defenders here included the men of “D” company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers, who on 11 December 1941 became the first Canadian Army troops to engage in combat in the Second World War.

After five days of fighting, Kowloon and the mainland fell to the Japanese. Major-General C.M. Maltby, Hong Kong’s military commander, refused Japanese demands for surrender despite there being no hope of relief from outside the colony. Instead, Maltby relied on his remaining, untested soldiers (including the bulk of the Canadian battalions) to defend Hong Kong island, where most of the civilian population lived.

Maltby split his island forces into two brigades, one encompassing the Royal Rifles of Canada, under the overall command of British Brigadier C. Wallis, the other, including the Winnipeg Grenadiers, under the overall command of Brigadier Lawson from Canada. For the next two weeks the troops of each brigade fought for their lives. Short of water, without adequate transportation — and pounded by the enemy’s superior artillery and command of the skies — the defenders did what they could to stem the Japanese advance following their amphibious landing on the island’s beaches.

Valour and Sacrifice

Despite their inexperience, the Canadians and their Allied comrades fought tenaciously to counter-attack the Japanese assault. There were numerous examples of bravery.

On 19 December, the second day of fighting on the island, the troops of “A” company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers had dug themselves into defensive positions following a retreat from the high ground of Mount Butler. Having surrounded the Winnipeggers, the Japanese began lobbing grenades into the Canadian positions. Company Sergeant-Major John Osborn picked up several live grenades and threw them back at the enemy. When one fell where Osborn could not return it in time, he shouted a warning to his men and then threw himself on the bomb to smother the explosion. He was killed instantly, but he saved the lives of several soldiers, who would soon be taken prisoner when the Japanese rushed the Canadian position.

Osborn was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross, the British Empire’s highest award for wartime valour.

The same day, Brigadier Lawson’s headquarters became surrounded by attackers at the Wong Nei Chong gap — a strategic pass where a main road cut through the centre of the island. With Japanese soldiers firing almost point-blank into his bunker, Lawson sent a radio message to Maltby, the colony’s commander, that he was going outside, “to fight it out” with the enemy. Lawson was quickly killed, but the Japanese would later make note of how he died “heroically.”

On Christmas Day, with ammunition in short supply and the defending soldiers in desperate shape, “D” company of the Royal Rifles was ordered to make what appeared to be a suicidal attack to retake lost ground at the south end of the island. According to an account from Sergeant George MacDonnell, the men received the orders in stunned silence. “Not one of them could believe such a preposterous order.” Attacking with bayonets, the Royal Rifles succeeded in taking the position — at a cost of 26 men killed and 75 wounded. Hours later, the exhausted survivors learned that the colony had surrendered. The Battle of Hong Kong was over.

Prisoners of War

The horror for those who remained, however, was only beginning. Although some Japanese units behaved with discipline after the battle, others carried out a campaign of terror — bayonetting wounded Allied soldiers in hospital, killing and raping nurses, and mutilating some prisoners.

The civilian residents of Hong Kong now faced years under harsh Japanese occupation. The captured British, Indian and Canadian soldiers — considered cowards by the Japanese for surrendering — became prisoners of war (POWs), first at camps in Hong Kong and later in Japan, where they endured years of beatings, hard labour and inadequate diets. Hundreds of the Canadian POWs died of illness, or from slow starvation.

In August 1945, almost four years after the fall of Hong Kong, the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced Japan’s surrender and ended the war in the Pacific. The American military delivered food and medical help to the camps, where POWs were suffering from diseases caused by vitamin deficiency.

DID YOU KNOW?

William Lore was the first Chinese Canadian officer in the Royal Canadian Navy and first officer of Chinese descent to serve in any of the Royal Navies of the British Commonwealth. In August 1945, he led a party of British Royal Marines ashore for negotiations for an official surrender with the Japanese in Hong Kong. Lore was the first Allied officer to enter Hong Kong since its capture. His party took control of the Royal Navy shore base and liberated Canadian, British and Hong Kongese prisoners being held at the notorious Sham Shui Po POW camp. On 16 September, Lore was present at the official surrender of Japanese forces in Hong Kong.

Memory

Of the 1,975 Canadians sent to Hong Kong, 290 were killed and 493 wounded during the battle and its immediate aftermath — proof, said veterans decades later, that they had resisted fiercely and courageously before surrendering to the enemy. Another 264 Canadians died as prisoners of war, while 1,418 survivors returned to Canada — many of them deeply bitter at the cruelty of their Japanese captors.

At home, political pressure forced the government in Ottawa to appoint a royal commission to investigate the circumstances of Canada’s involvement in Hong Kong. The sole commissioner, Chief Justice Lyman Duff, misinterpreted or ignored evidence and exonerated the Cabinet, the Department of National Defence and senior members of the military’s general staff. In 1948, a confidential analysis by General Charles Foulkes, chief of the general staff, found many errors in Duff’s assessment, but concluded that proper training, staffing and equipment would have made little difference, given the overwhelming odds facing the defenders.

The 554 Canadians who died in Hong Kong and in prisoner camps afterwards are remembered today by a memorial to all of Hong Kong’s defenders at the Sai Wan Bay War Cemetery there. This and the Stanley Military Cemetery in Hong Kong also hold the individual graves of 303 Canadian soldiers, 108 of whom are unidentified. Another 137 Canadians, most of whom died as prisoners of war, are buried at the British Commonwealth War Cemetery in Yokohama, Japan.

See also Canada’s Road to the Second World War.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom