The question of what it means to be a Canadian has been a difficult and much debated one. Some people see the question itself as central to that identity. Canadians have never reached a consensus on a single, unified conception of the country. Most notions of Canadian identity have shifted between the ideas of unity and plurality. They have emphasized either a vision of “one” Canada or a nation of “many” Canadas. A more recent view of Canadian identity sees it as marked by a combination of both unity and plurality. The pluralist approach sees compromise as the best response to the tensions — national, regional, ethnic, religious and political — that make up Canada.

One or Many Canadas?

In many old countries, the name of the dominant ethnic group is synonymous with the country’s identity — for example Germans in Germany, or French in France. But Canada had numerous First Nations, as well as multiple ethnic settler groups from the start. This makes it harder to pin down a Canadian identity in the traditional sense.

The question of what it means to be a Canadian — what moral, political or spiritual perspectives it involves — has been a difficult and much-debated one. Some people see the question itself as central to that identity. The main reason for this is that Canadians have never reached anything close to a consensus on a single, unified conception of the country. According to some observers, this is because fundamental social divisions prevent such a conception from taking shape. First, there is the separation between the Indigenous peoples and the European colonists and their descendants. Second, there is the separation between the famous “two solitudes.” This term referred originally to those colonists with either French or British ancestry. Third, extensive immigration since the Second World War has produced a poly-ethnic society. Some see that as incompatible with a unified idea of the country.

As a result, most notions of Canadian identity have shifted between the ideas of unity and plurality. They have emphasized either a vision of “one” Canada or a nation of “many” Canadas. A more recent, postmodernist view of Canadian identity sees it as marked by a combination of both unity and plurality. Another approach moves in between, rather than combining these two extremes. It views Canada as more-or-less cohesive, characterized by what Charles Taylor called “deep diversity.”

Crown and Economy

The unified idea of Canadian identity has taken various forms throughout history. Often, it depends on which authority is given the final word over matters of profound disagreement.

Originally, there were two main competing views on the question of Canadian identity. Monarchists pointed to the Crown and the country’s ties with Britain. Mercantilists, on the other hand, advocated protectionist economic policies in order to facilitate exports. This view was held by the Chateau Clique in Lower Canada and the Family Compact in Upper Canada. Over time, the Crown lost virtually all its power. It now plays a largely symbolic role in the country. Those that put the economy first believe that Canada is at its best when it can provide its citizens with an “efficient society.”

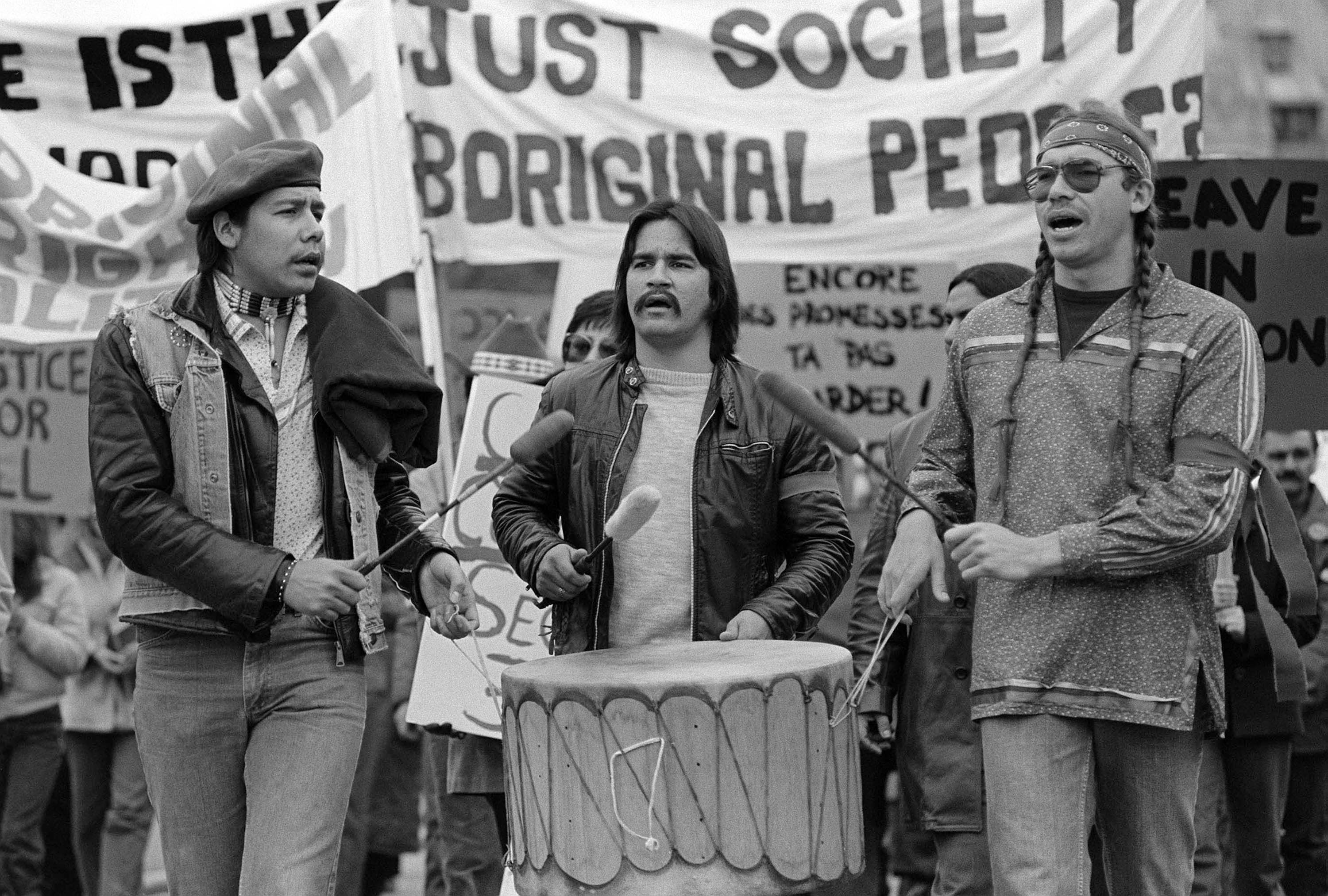

Populism and the “Just Society”

There have been at least two other contenders for the role of “Canada’s unifying idea.” One argues that in a democracy, the people have ultimate authority. This view draws upon the American republican model. It inspired the failed Canadian rebellions of 1837–38. It also reflects the various populist movements and parties that have been influential at times. These include the Social Credit parties in the west and Quebec, as well as the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and the Reform Party.

The second is the theory of a “Just Society.” It formed the basis of former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s view of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982). He inserted this into the Constitution during its patriation from Britain. Trudeau’s “Dream of One Canada” calls for uniformly respecting the individual rights of all Canadians. This is why he so strongly opposed the failed Meech Lake Accord (1987). It would have recognized Quebec as a “distinct society” and allowed its citizens to be treated differently than other Canadians.

Threats to Canadian Society

All of these views link to the idea that Northrop Frye called a “garrison mentality.” Margaret Atwood identified it as the “survival” theme present in English Canadian literature. It sees plurality — in the form of certain external “others” — as a threat to the integrity of Canadian society.

These threats include: untamed nature, as symbolized by the harshness of winter, the wilderness, or Indigenous peoples; the separatist movement of some Québécois nationalists; and the “balkanization” of the country due to a multicultural policy that some critics believe has led to ethnic ghettos rather than the assimilation of immigrants. This view has led its proponents to take a belligerent stance towards these supposed threats.

Genius for Compromise

The pluralist conception of Canadian identity sees accommodation as the best response to the tensions — national, regional, ethnic, religious and political — that make up Canada. According to this view, the rights contained in the Charter do not form a unified whole. Rather, they must be balanced against each other. This is fully in keeping with Canadian tradition.

Northrop Frye put it this way: “The Canadian genius for compromise is reflected in the existence of Canada itself.” Sir John A. Macdonald, the country’s first prime minister, praised the resolutions that would become the British North America Act (1867) for bearing “the marks of compromise.” Perhaps it is also why the winner of a 1972 CBC Radio contest in search of a Canadian equivalent to the phrase “as American as apple pie” was neither “as Canadian as maple syrup” nor “as Canadian as hockey.” It was “as Canadian as possible, under the circumstances.”

Conversation, Not Negotiation

The view of Canada as a deeply diverse community stresses the importance of resolving conflicts by using conversation instead of negotiation. This view believes that conversation builds toward the common good by focusing on listening and working to a shared understanding. Negotiations, in contrast, involve rival sides trying to get the best results for themselves.

This view of the common good in Canada encourages a strictly political, rather than national, conception of the country. In this view, Canada constitutes a “civic” community — a community of citizens, rather than a “nation.” National communities are considered largely cultural entities. That said, the civic or political conception of Canada recognizes that the country contains many other kinds of communities, including the national. As a result, those who support this approach tend to describe Canada as “multinational” or as forming a “nations-state.” They call on its citizens to talk through their conflicts rather than negotiate them, though negotiation is often seen as unavoidable.

Indeed, most Canadians have carried out this approach in a way that reflects small-l liberal ideology. In the United States, conservatism is more dominant. In Scandinavian countries, democratic socialism is more typical. As a result of this emphasis on liberalism, Canadian political parties hoping to form a government have stressed the more liberal elements of their platforms.

Recognition for Ethnic Groups

According to this approach, national communities should be distinguished from the civic or political sort. They should also not be equated with ethnic communities. (See also: Ethnic Identity.) The question is whether the ethnic group wants recognition and self-determination from the state, or if they identify primarily with Canada.

Ethnic groups seeking self-determination and recognition have included Indigenous peoples, French-speaking Québéckers, English-speaking Canadians, and perhaps the Acadians. Examples of ethnic groups not seeking such status include the many hyphenated Canadians (e.g., Scottish, Chinese, African-Canadians).

English Canadians are sometimes described as forming a “nation that dares not speak its name.” They tend not to see themselves as constituting a distinct community. Instead, they are often viewed as just one of the two linguistic groups in bilingual Canada. English Canadians have had the luxury of subscribing to this view. As the dominant group in the country, it is all too easy to overlook the distinction between one’s national community and the country as a whole.

Each of these positions has been well-represented in the debate over the nature of Canadian identity. There is no reason to think that the argument will end any time soon.

See also: Canadian Identity and Language.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom