Historical Context

The Southeast Asian refugee crisis resulted from several conflicts in that part of the world. Occupied by the Japanese army during the Second World War, the colonies of French Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos) gained their independence in 1954 after eight years of a hard-fought war that claimed over 500,000 victims and left Vietnam divided into two rival states. Not long afterward, a new armed conflict, the Vietnam War, broke out, with major repercussions for all of continental Southeast Asia. With the help of Russia and China, the Communist forces of North Vietnam supported a guerilla movement that fought the U.S.-backed, pro-Western government in South Vietnam.

After many years of battle, the parties to the conflict signed the Paris Peace Accords on 27 January 1973. These agreements called for the withdrawal of US forces, the release of civilian detainees and prisoners of war, the unity and territorial integrity of Vietnam, and the holding of free elections in South Vietnam. But this last condition was not met, and on 30 April 1975, Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, fell to the Communist forces from the North. About 140,000 people, fearing that the new regime would persecute them for having sided with the United States, then fled the country, some by helicopter, some by boat. Many of them were rescued by the US Navy. A few weeks later, Canada announced that it would be accepting refugees from Vietnam. As a result, over the years 1975 and 1976, Canada welcomed over 6,500 Vietnamese as political refugees; 3, 000 of them had no relatives in Canada.

Meanwhile, back in Vietnam, the new regime took hostile repressive measures against the South Vietnamese, stripping them of their homes and possessions and preventing them from holding jobs or pursuing an education. Civilian and military officials of the former South Vietnam were sent to work camps, known as “re-education camps.”

The situation in the other countries of former French Indochina was no better. By the end of 1975, Cambodia and Laos also were governed by totalitarian regimes. In Cambodia, on 17 April 1975, the Khmer Rouge took the capital, Phnom Penh, along with other cities, thus ensuring their domination of the entire country. Led by the ideologue Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge abolished private property, sent most of the population of the cities to work camps in the country, and persecuted ethnic and religious minorities. Out of a population of 8 million Cambodians, an estimated 1.4 to 2.5 million perished during this period — executed, tortured to death, or killed by forced labour, famine or lack of medical treatment. In 1978, an armed conflict broke out between Vietnam and Cambodia, adding to their peoples’ woes. In Laos, on 2 December 1975, the Communist revolutionaries of the Pathet Lao took power, abolished the monarchy, and proclaimed the Lao People's Democratic Republic.

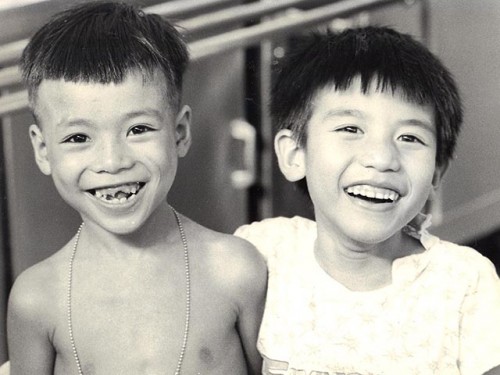

The tense political situation, rapidly deteriorating living conditions and human rights violations in these countries triggered a vast wave of emigration. In Vietnam, the 2 to 3 million Vietnamese of Chinese ethnic origin were especially hard hit by the nationalization of private businesses in 1978 and the regime’s mistrust of them (the result of skirmishes along the Vietnam/China border in February 1979). With the encouragement of the government authorities, they began to leave Vietnam by boat. Many South Vietnamese, seeing no future for their children in the new Vietnam, decided to join the migration. Following the Vietnamese army’s invasion of Cambodia in 1978, several thousand Cambodians fled their country on foot, hoping to find refuge in Thailand.

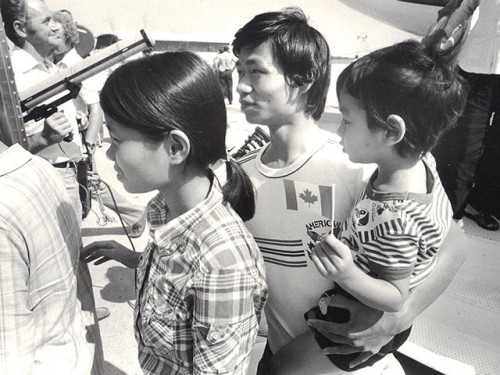

Over the ensuing decade, an estimated 3 million people thus left by sea or land for other countries of Southeast Asia. Over 1 million people departed Vietnam aboard unseaworthy makeshift vessels, hoping to reach international waters and be rescued there. But first they had to face huge risks — drowning, hunger, dehydration, attacks by pirates, sexual assaults and even murder. Some of the refugees who survived all these perils were then stuck for months in crowded refugee camps in Hong Kong, the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia, while others remained confined to their vessels because no country would allow them to land.

Origin of the Expression “Boat People”

Because of the perilous conditions under which most refugees fled former French Indochina, they came to be referred to collectively as “boat people.” This term was first used in 1975 and was popularized in the media in 1979. But it is now regarded as pejorative — an example of the kind of simplistic, racist language so often used in connection with refugees. It is most closely associated with the Vietnamese who left their country starting in 1975 and continuing into the 1980s and who indeed accounted for the largest number of refugees from former Indochina at the time. But the term is inaccurate when applied to Cambodian and Laotian refugees, who fled their countries mainly by land, and thus fails to reflect the ethnic diversity of this region. It should also be noted that large proportions of these refugees were of Chinese ethnic origin, including 40 per cent of the Vietnamese, 25 per cent of the Cambodians and 20 per cent of the Laotians admitted to Canada at that time.

Consequently, it is preferable to refer to these people as “Indochinese refugees” or “Southeast Asian refugees.” Neither term is perfect: the first hearkens back to colonialism, while the second is imprecise, in that there are eight other countries in Southeast Asia. But both have the advantage of explicitly recognizing these people’s status as refugees and identifying their geographic origin to some extent.

Evolution in Canadian Humanitarian Attitudes and Legislation Regarding Refugees

After the Second World War, Canada became more open to refugees. In 1956, Canada accepted 37,000 Hungarian refugees, responding both to public pressure and to the need for workers in Canada’s booming economy. In 1969, Canada at last signed the United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, first approved in 1951. Countries that sign this Convention have an obligation to provide international protection to refugees. More specifically, these countries must make provisions to resettle refugees, and when their protection cannot be guaranteed in the country where they first seek refuge, consider their resettlement in a third country. After signing the Convention in 1969, Canada exercised flexibility in admitting refugees several times in the 1970s: Tibetan refugees in 1970, ethnic Asian refugees expelled from Uganda in 1972 and Chilean refugees in 1973. But in all of these cases, these refugees were admitted under exceptional measures (see Immigration Policy in Canada). When the Indochinese refugee crisis began, there was still no Canadian law recognizing refugees as a special category of immigrants.

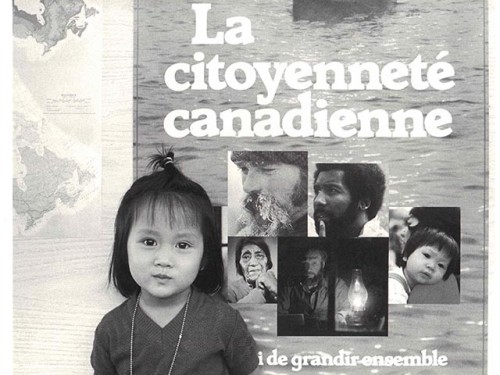

This changed in April 1978, when the new Immigration Act, 1976 came into force. This statute established three new categories of immigrants eligible for admission to Canada: refugees, Canadian citizens’ family members, and permanent residents and independent immigrants selected on economic grounds. Among other changes, the new Immigration Act identified, for the first time, refugees as a distinct category of immigrants and adopted the definition of a refugee within the meaning of the Convention. By including this definition in its immigration legislation, Canada clearly stated its intention to fulfill its legal obligation toward refugees. The Act also established a system for determining refugee status, provided for the admission of designated categories of refugees on humanitarian grounds, and established one of the most innovative aspects of Canada's refugee resettlement program — the private sponsorship of refugees.

At the time of the Indochinese refugee crisis, the government of Québec was deeply involved in negotiations with the federal government to recover certain powers regarding immigration. The province had established its own ministry of immigration in 1968, and in 1975 signed the Andras/Bienvenue agreement, which provided for collaboration between the Québec and federal governments in selecting refugees to be settled in Québec.

Another important step was taken in February 1978, when Québec and Canada signed the Cullen/Couture agreement, which allowed Québec to choose its immigrants according to its own criteria. This agreement led to a Québec immigration policy based on three fundamental principles: selection without discrimination, priority for family reunification, and humanitarian considerations. Québec also established its own sponsorship program, because it believed that adaptation of refugees should come under provincial jurisdiction. As a result of this measure, Québec was able to directly sponsor 10,000 refugees from Southeast Asia. From 1979 to 1982, Québec thus welcomed 22 per cent of all refugees resettled in Canada.

The Hai Hong Incident and Canadian Public Opinion

In several respects, the Hai Hong incident can be seen as a turning point in the Canadian response to the Southeast Asian refugee crisis. The Hai Hong was a ship that had sailed for Indonesia from Vietnam with 2,500 passengers on board (its actual capacity was only 2,500). En route, the ship was blown off course and damaged in a typhoon. When it attempted to land its passengers, first in Indonesia and then in Malaysia, both countries refused permission, on the grounds that these passengers — mostly Vietnamese of Chinese ethnic origin — had paid the Vietnamese authorities to be allowed to leave and hence were not refugees.

After 17 days at sea, with its engine failing and practically no food or water left on board, the Hai Hong dropped anchor off Port Klang, Malaysia on 9 November 1978. Malaysia, which had not signed the UN Convention on the status of refugees but had already admitted over 35,000 refugees from Vietnam, threatened to tow the Hai Hong out to sea and abandon the passengers to their fate.

The plight of the Hai Hong galvanized the international community. The incident soon drew attention around the world, and Canadian newspapers began pressing the Canadian government to act. Aware that a quick response was needed and wanting to help, Canada faced a dilemma: if it admitted the passengers from the Hai Hong now, it would be giving them precedence over tens of thousands of refugees who had already spent months waiting in UN camps.

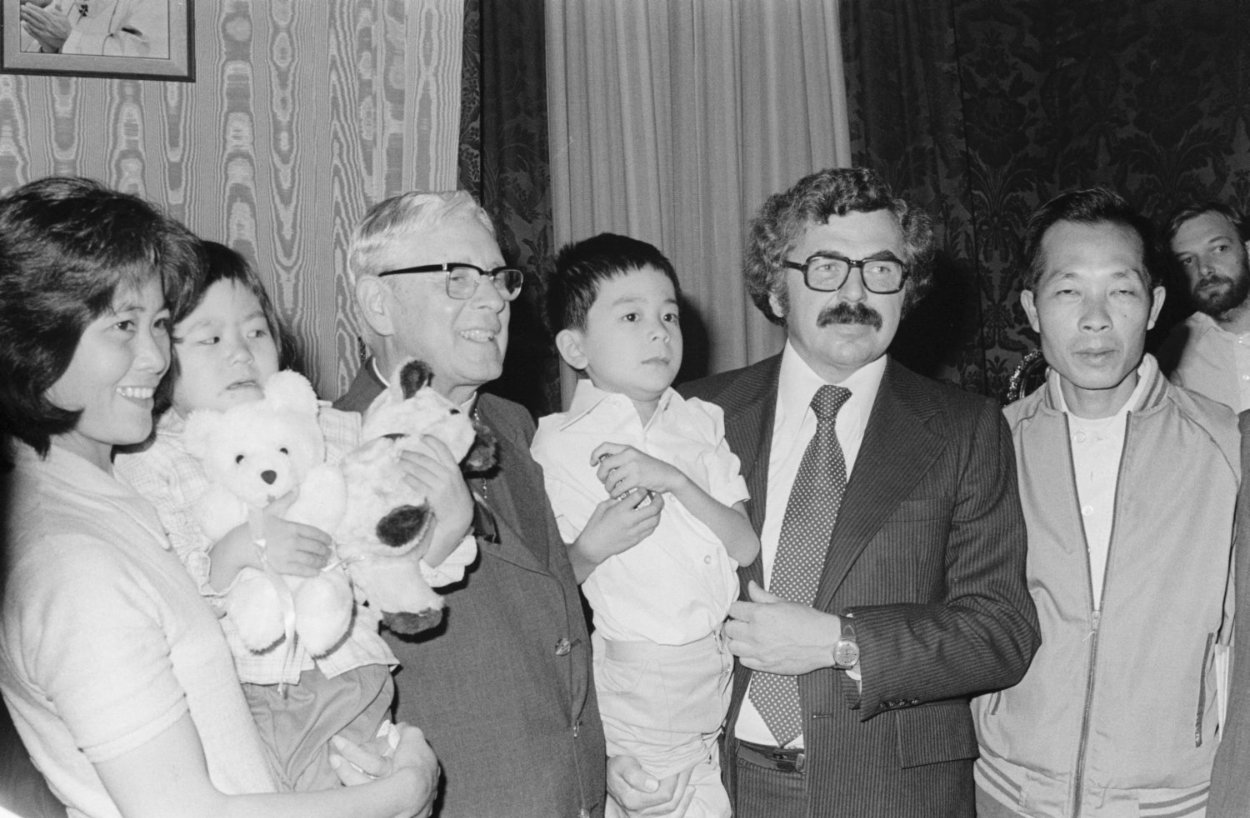

In a sense, it was the government of Québec that provided the solution. On 15 November 1978, the province’s minister of immigration, Jacques Couture, announced that Québec was prepared to welcome at least 200 refugees from the Hai Hong under the new Cullen/Couture agreement. The federal House of Commons quickly agreed that 600 of the ship’s passengers would be resettled in Canada and added to Canada’s annual immigration targets. Several other countries (the United States, France, Germany and Switzerland) followed Canada’s example and agreed to help by processing the passengers’ refugee applications and giving them priority for relocation. In the final analysis, the Canadian government’s decision to intervene and accept more refugees, together with pressure from the public and the sympathetic response to the distress of these Vietnamese refugees, played a decisive role in the events that followed.

Canada Accepts 60,000 Refugees in Two Years

By the end of 1978, over 200,000 Indochinese refugees had managed to reach temporary camps operated in Southeast Asia by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The countries that had signed the Convention had agreed to accept only 80,000 refugees so far. The fate of a significant number of refugees thus remained uncertain, and the pressure on the countries to which they were fleeing increased. In January and February 1979, an additional 20,000 refugees (mainly of Chinese ethnic origin) left Vietnam, and the numbers kept growing in the months that followed: 13,000 arrived in March, 26,000 in April, 51,000 in May and 57,000 in June. In addition, that same April and May, between 50,000 and 80,000 Cambodians crossed the land border into Thailand, where they were joined by 10,000 fellow Cambodians of Chinese origin.

As of May 1979, only 8,500 refugees from former Indochina had been resettled in the countries where they had first taken refuge; the international response had clearly been inadequate. On 20 and 21 July 1979, in Geneva, the UNHCR held a conference on refugees and displaced persons in Southeast Asia. Sixty-five countries attended, including Canada. On 18 July, a few days before the conference began, Canadian minister of External Affairs Flora MacDonald announced that Canada was increasing its target significantly and would be accepting 50,000 refugees by the end of 1980, half of them through its new private sponsorship program.

The Canadian government quickly chartered 76 airplanes in order to transport 15,800 refugees by the end of 1979. Reception centres were set up at Canadian Forces Base Longue-Pointe (near Montréal) and Canadian Forces Base Griesbach (near Edmonton) to handle the refugees arriving on the charter flights.

In April 1980, Canada increased its target again, announcing that it would be accepting 10,000 more people, for a total of 60,000 refugees accepted in 1979-1980. Indochinese refugees accounted for 25 per cent of all new immigrants to Canada during this period, a proportion that has never been equalled since.

Importance and Commemoration of the Events

The successful resettlement of the Indochinese refugees was made possible by the combined efforts of the government of Canada, its civilian and military personnel, and private citizens who applied to sponsor individuals and families. Of the 60,000 Indochinese refugees admitted to Canada in 1979 and 1980, about 26,000 were sponsored by the government. The remaining 34,000 were sponsored by the private sector or by members of their own families, which got the new private sponsorship program off to a great start. Throughout the 1980s, Canada continued to welcome Indochinese refugees. In total, some 200,000 Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians have been resettled in Canada — the highest rate per capita among all of the countries that have accepted such refugees.

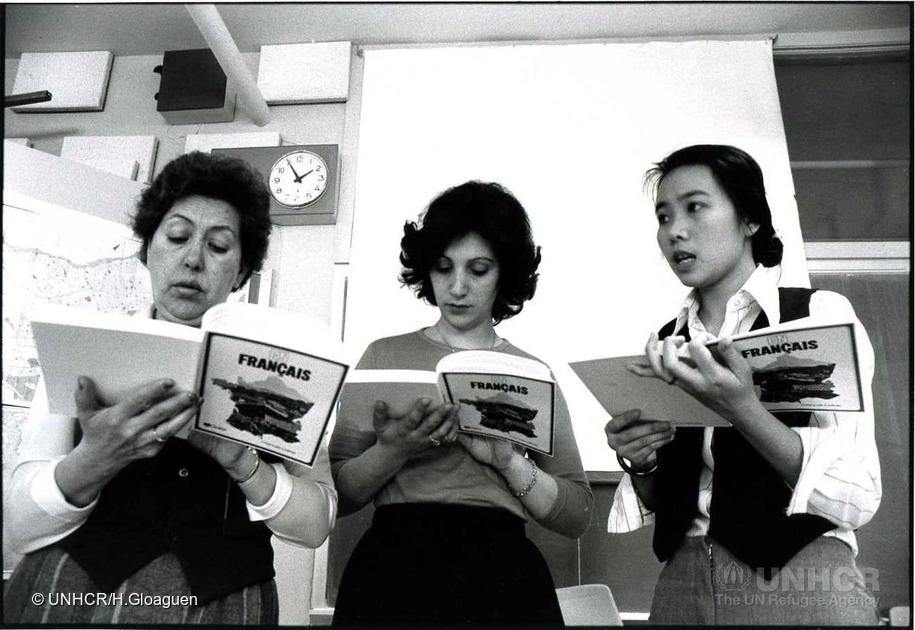

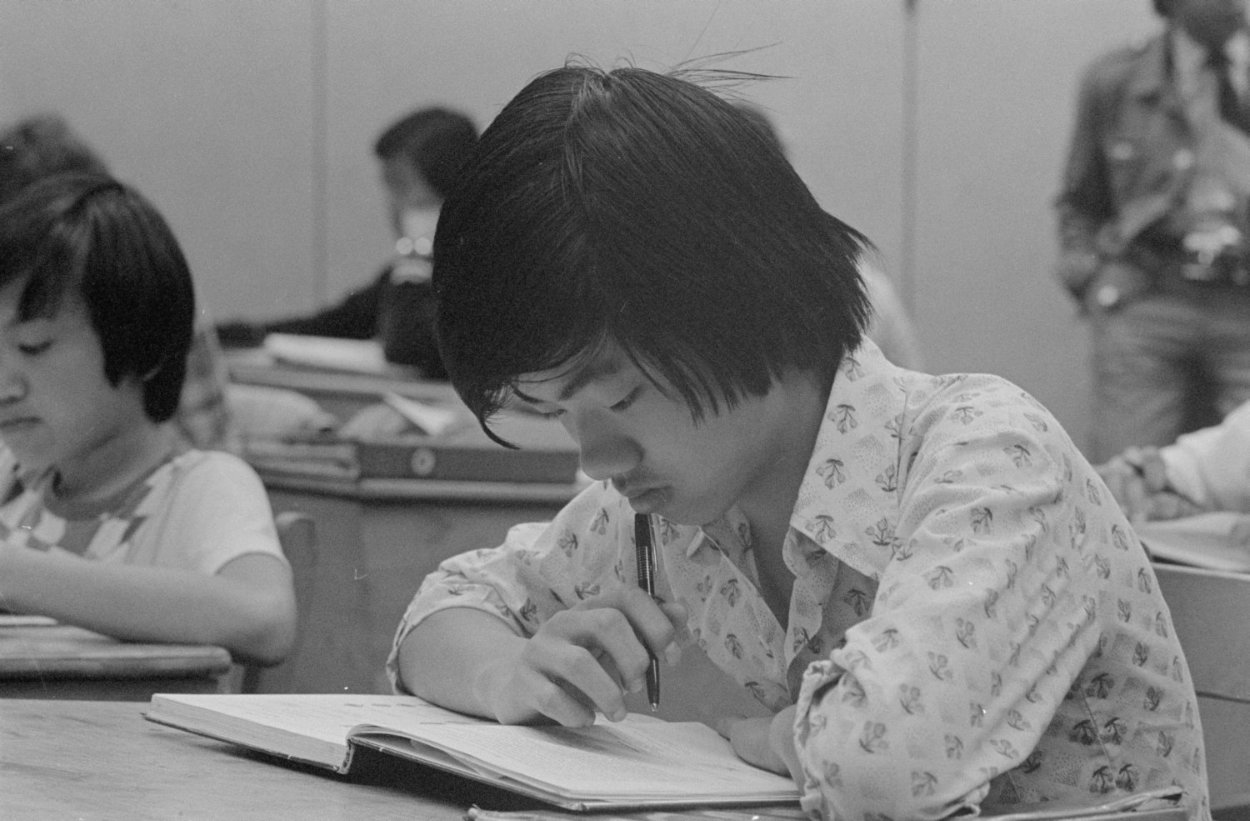

To help the new arrivals to integrate into Canadian society, orientation and education centres offer classes where they can learn English or French and take them on outings to familiarize them with the communities in which they now live. The organizations and citizens’ groups that sponsor refugees welcome them into their communities and even their homes and help them to adjust to a new culture, secure housing and either find jobs or continue their studies.

In return, Canadians of Vietnamese, Cambodian and Laotian origin have enriched Canadian society by making important contributions in many spheres, including the economy, politics, the arts, science and sports. In the 2011 Census, 220,425 Canadians described themselves as being of Vietnamese ethnic origin, 34,340 of Cambodian (or Khmer) ethnic origin, and 22, 090 of Laotian ethnic origin. In addition to these 276,855 people, there are a few tens of thousands of Canadians of Chinese ethnic origin who came to Canada from Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos.

Canada’s positive, humanitarian response to the Southeast Asian refugee crisis has certainly helped to establish this country’s reputation as a land that welcomes refugees. Previously, Canada had not always welcomed refugees with open arms and had discriminated against certain groups, two examples being Canada’s refusals to admit the passengers from the vessels SS Komagata Maru in 1914 and MS Saint Louis in 1939. Years after the Southeast Asian refugee crisis, Canada showed its generosity once more when it resettled over 40,000 Syrian refugees (see Canadian Response to the Syrian Refugee Crisis).

The episode in Canadian history known as the "boat people" refugee crisis has been commemorated in various ways. In 2015, the Canadian Parliament passed the Journey to Freedom Day Act, making 30 April a national day of commemoration of the exodus of Vietnamese refugees and their acceptance in Canada after the fall of Saigon and the end of the Vietnam War. However, the passage of this bill by the Canadian Senate caused some controversy with the government of Vietnam, where 30 April is celebrated as Liberation Day.

A documentary film entitled A Moonless Night: Boat People, 40 Years Later, created by Thi Be Nguyen and Marie-Hélène Panisset, was released in 2016. On 20 June 2017, to mark World Refugee Day, Historica Canada released a new Heritage Minute about the welcoming of the Vietnamese “boat people” to Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom