Chartered banks, sometimes known as commercial banks, are public corporations that are licensed by the federal government to operate a banking business within Canada (see Banking in Canada). By issuing these licenses (or charters), the Canadian government regulates and controls the country’s economy by influencing the amount, availability and distribution of money, and the terms or cost of accessing and distributing that money (interest rates). Chartered banks are regulated by the federal Bank Act and supervised by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions. Chartered banks in Canada accept deposits from the public and extend loans (such as mortgages) for personal, commercial, and other purposes. Banks also own and operate trust companies, securities dealers and insurance companies and offer such services as investment banking, international banking and more.

How do Chartered Banks Work?

At their core, banking businesses receive and hold deposits from the public (for which the banks pay a fee, or interest rate to the depositor). Banks keep a portion of these deposits on hold in case the depositor wants some of the money back (called a reserve), and lend out the balance of the deposit as loans or mortgages to other customers who want to borrow — banks charge those customers a higher interest rate. The bank makes money on the difference in interest rates it pays the depositor and the rates earned from the borrower. To do this business requires a charter from the government.

Creation and Regulation of Chartered Banks in Canada

Prior to Confederation in 1867, banks in Canada were chartered by royal assent. Their daily affairs were monitored and supervised by the governments of Upper and Lower Canada until 1841, and by the government of the Province of Canada from 1841 to 1867, though always with the oversight of the authorities in Great Britain. After Confederation, chartered banks were both licensed and supervised by Parliament (see Banking in Canada).

In 1980, the federal government allowed the creation of banks by letters patent issued by the Ministry of Finance, a process that no longer required special approval by Parliament. As well, all banks were classified as either Schedule I banks (being those widely owned by the Canadian public), Schedule II banks (being foreign-owned banks or closely held Canadian-owned banks that can accept deposits from Canadians), or Schedule III banks (being branches of foreign-owned banks that are restricted in their size and the assets they can hold).

Did you know?

The Bank Act is the law passed by Parliament in 1871 to regulate Canada’s chartered banks. The Act has three main goals: protecting depositors’ funds, insuring the maintenance of cash reserves (see Monetary Policy) and promoting the efficiency of the financial system through competition.

Banks are heavily regulated under the federal government’s Bank Act, which historically was updated every 10 years along with the re-chartering of the banks themselves. This forced banks to adopt sound business practices. This was changed to every five years in 1992. The Bank Act specifies such issues as: the definition of the business of banking, the requirements for establishing a new bank, the types of assets a bank can own, what areas of business a bank can operate in, accountability of the banks to their shareholders, and much more.

The federal government’s agency for supervising and regulating all chartered banks is the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI), reporting to the minister of finance. Chartered banks are regularly inspected for their financial health and to ensure they are following the rules of the Bank Act.

The banks joined together in 1891 to create the Canadian Bankers Association, to represent their joint interests and to help shape public policy on banking matters.

History of Canada’s Chartered Banks

Banking has been around as a business practice for centuries. Our system of banking, as we know it today, started to form in the 1600s in England and Europe.

The first initiative to establish a bank in Canada occurred in 1792 in Lower Canada by a group of Montreal merchants who proposed forming the Canada Banking Company. However, this company did not survive. Intermittent wars and the lack of approval for banking from the British government stalled other efforts to create a bank. It was not until 1820 that royal assent from Britain was given to create the first chartered bank in British North America, the Bank of New Brunswick, followed by the Bank of Montreal in 1822.

By 1867, there were 35 chartered banks with 123 branches. By 1901, the chartered banks were the biggest sources of Canadian saving deposits, accounting for 75 per cent of total public savings.

At the time, each bank was relatively small. They were originally organized to service a small group of shareholders (and the bank’s directors) in a local region. Their principle business was short-term lending to these customers to finance their inventory and cycle of business. This meant that when this small group of same-industry customers got into trouble, so too did the bank, and reckoning came quickly when depositors demanded their money back. Smaller regional banks could not manage the demands of diversifying the risk of their business as effectively as a larger bank could once the national economy grew quickly across Canada — they could not transfer funds regionally to meet the varying needs of different industries and their operating cycles. These pressures caused Canada’s chartered banks to merge into larger entities or else fail.

Through such mergers and bank failures, the number of prominent chartered banks in Canada has steadily declined such that today there are nine Schedule I chartered banks in business that generate revenues greater than $1 billion. While the concentration to fewer and larger chartered banks occurred, the industry developed a branch system of banking, where each chartered bank operates many branches spread across the provinces and territories.

| Largest Schedule I Banks in Canada |

| Royal Bank of Canada |

| Toronto-Dominion Bank |

| Bank of Nova Scotia |

| Bank of Montreal |

| Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce |

| National Bank of Canada |

| Laurentian Bank of Canada |

| Canadian Western Bank |

This trend to a small number of larger chartered banks caused government regulators to demand tight control of their risks. In its efforts to manage the risk of the chartered banks and to ensure depositors safety, the federal government often restricted the range of business activity banks could enter into through the Bank Act.

The “Big Five” and Second Tier Banks

Chartered banks are generally grouped under two non-official categories: the largest (“Big Five”) national banks, and the smaller, second tier banks.

The “Big Five,” or the largest five national banks by total assets are: Royal Bank of Canada (RBC), Toronto-Dominion Bank (TD), Bank of Nova Scotia (Scotiabank), Bank of Montreal (BMO) and Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC). These Schedule I banks operate as international conglomerates that own and operate subsidiaries in other countries.

Second tier banks include National Bank of Canada, Laurentian Bank of Canada and Canadian Western Bank. These banks mainly operate nationally or in smaller domestic Canadian markets (Schedule I banks), or are the Canadian subsidiaries of foreign banks or closely held Canadian banks (Schedule II), or branches of foreign banks (Schedule III).

Deregulation of Financial Services and New Products: 1960s–1990s

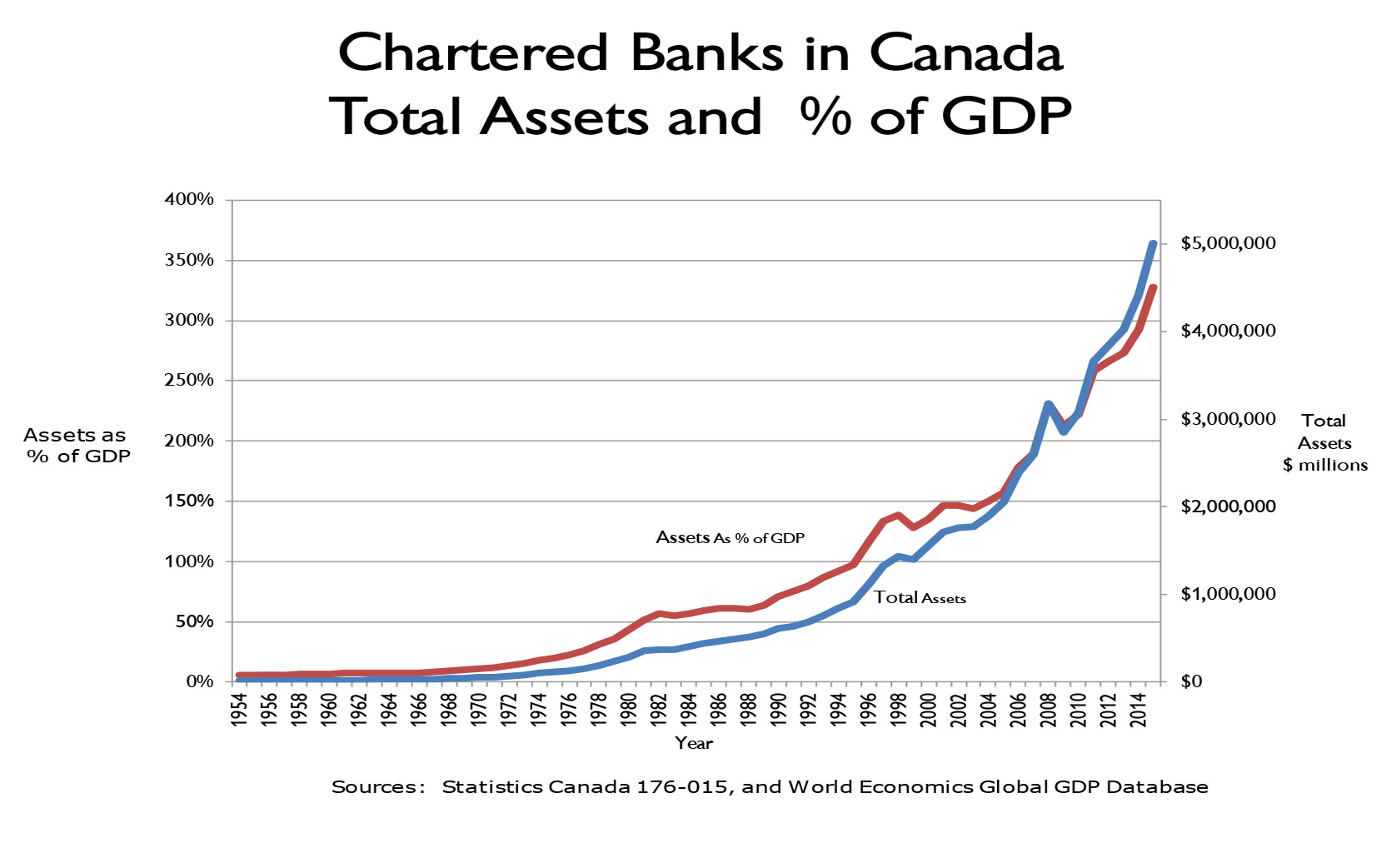

Chartered banks were prohibited from issuing mortgages not insured under the National Housing Act until the 1967 Bank Act revision, and they could not charge interest rates greater than 6 per cent up to 1968 (when the government stopped regulating the interest rate charged). When these rules were changed by an amendment to the Bank Act, chartered banks grew dramatically.

At the same time, chartered banks began to compete by being innovative and introducing new products for their customers. In 1968, Toronto-Dominion Bank, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, Royal Bank and National Bank of Canada jointly introduced credit cards to Canada when they launched Chargex (later renamed VISA). Chartered banks began marketing personal chequing accounts to their clients in the late 1950 and early 1960s, and daily interest savings accounts in the late 1970s. These innovations greatly added to the growth of chartered bank assets.

Growth also occurred because of the chartered banks’ new strategy of expanding their international business. The banks’ foreign deposits and foreign loans as a proportion of total assets and liabilities more than doubled between 1960 and 1970, to 21 per cent and 10 per cent respectively. Their total foreign deposits as a percentage of total Canadian deposits also doubled to almost 50 per cent by 1970 (see Foreign Investment).

Growth continued into the 1980s, when the banks were allowed to enter the investment banking and stock brokerage industry, dubbed “Canada’s Little Bang” (see Stock and Bond Markets).

Did you know?

Canada’s “Little Bang” describes a series of provincial and federal regulatory changes between 1987 and 1992 that allowed chartered banks to own investment dealers, mutual fund companies, insurance companies and trust companies.

The real estate collapse in Canada in the early 1990s caused particular distress to the trust company sector, which had lent considerably to that industry. These financial troubles presented the opportunity for chartered banks to acquire almost all of Canada’s troubled trust companies, to the extent that the trust company industry all but disappeared. This gave the chartered banks a tremendous growth spurt.

Chartered Banks in the 21st Century

In 1998, the Royal Bank of Canada and the Bank of Montreal announced their intention to merge and create a combined, larger bank. This was followed by news that the Toronto-Dominion Bank and Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce intended to merge. However, the federal government prohibited these mergers on the basis that it was not in the best interests of the industry to have such large and dominant companies (see Royal-Montreal Bank Merger).

As a result, many Canadian chartered banks have grown by expanding into other financial markets. Many have bought banks located in the United States and other countries in order to expand their business. Many have also expanded into the asset management business, both inside and outside Canada, including mutual fund and pension fund management.

Though chartered banks can have subsidiaries in the insurance business, they cannot sell many types of insurance in their branches.

Credit Unions and Caisses Populaires

The main competitors for the chartered banks are Canada’s credit unions and cooperatives (such as the caisses populaires in Quebec), which are financial institutions owned by their depositors and not by public shareholders, as is the case with chartered banks. Credit unions provide many of the same financial services and products as chartered banks. They mainly operate at the local level and are governed by provincial banking laws. However, in 2012, the Bank Act allowed for the creation of federal credit unions, the first of which was established in 2016.

To a lesser extent, government-owned crown financial institutions that lend to specific industries (such as Farm Credit Canada and the Business Development Bank of Canada) are also competitors.

Canadian Banks and the Recession of 2008–09

Despite the challenges presented by the 2008 global financial crisis, Canadian chartered banks emerged relatively unscathed by the event (see Recession of 2008–09 in Canada). This was due to the regulatory framework surrounding Canada’s banking sector, which had been significantly overhauled in the mid-1980s following the collapse of two chartered banks and the subsequent creation of the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (see Estey Commission). According to federal regulations, Canadian banks are expected to maintain low debt-to-equity ratios, which sheltered them from the financial crisis and ensuing recession.

In 2012, Global Finance magazine ranked five of Canada’s chartered banks as among the safest 25 banks in the world. The Global Competitiveness Report, issued by the World Economic Forum, consistently ranks Canada’s chartered banks as the soundest in the world.

Financial Technology (Fintech) in Canada

Today, the emergence of fintech companies presents a competitive threat to the chartered banks. These are financial firms that provide customers with entirely-online banking services, including online lending, retail payment services, robo-advisors and more. The challenge these fintech firms pose to the large financial institutions is their low cost of service, their relative lack of regulation, and their general anonymity in terms of a client relationship. These characteristics eat into the profits of the chartered banks, allow fintech to operate more easily, and loosen the banks’ relationship with their established clients. Chartered banks have responded by either acquiring or partnering with such firms, offering similar services, or ignoring the threat.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom