Child Migration to Canada Throughout History

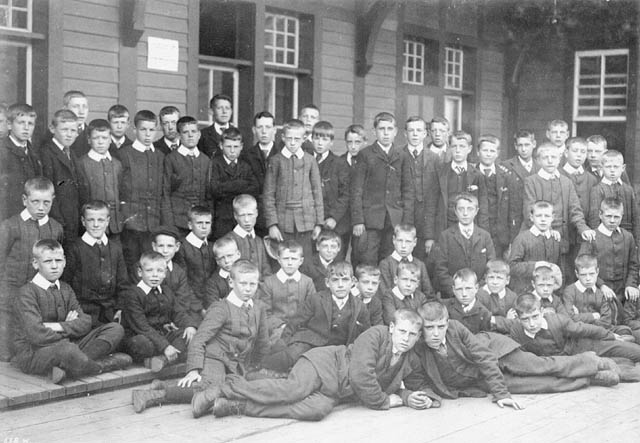

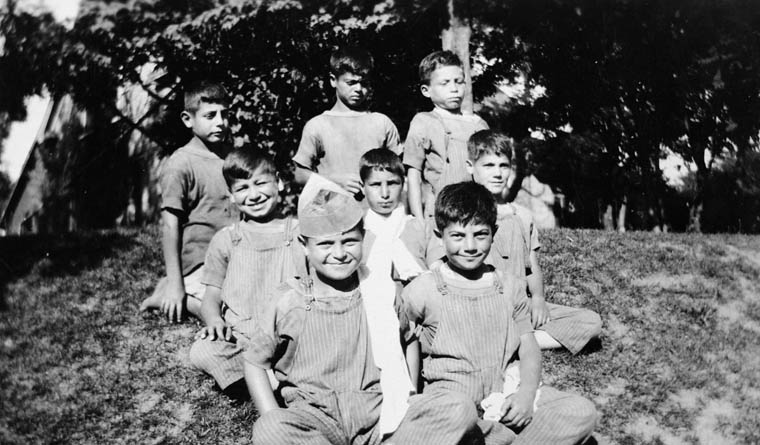

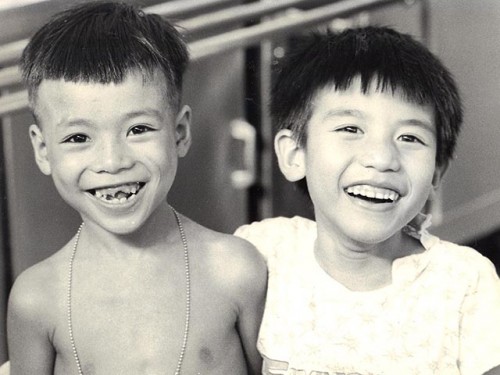

The migration of children to Canada is not a new phenomenon. During the 1847 Irish Famine migration to British North America, thousands of children became orphaned. Some were placed for adoption while others were placed in orphanages or government care. Also, between 1869 and the late 1930s, over 100,000 children were sent to Canada from Britain. Termed the British Home Children, these children were poor or orphaned and sent to Canada by philanthropic agencies in hopes of having a better life with foster families or in group homes. While some children benefited from this arrangement, many experienced neglect and abuse upon arrival. More recently, unaccompanied minors also arrived during the displaced migration movement following the Second World War, as well as the fall of Saigon in the late 1970s (see Vietnam War; Southeast Asian Refugees).

Over 100,000 “home children” were sent from the U.K. to Canada to work as labourers, from 1869 through to the 1940s. The podcast finds out who they were and what happened once they arrived here. Plus, Alan Dilworth tells the story of his grandfather, Tom Selby, who arrived in Canada at the age of 8.

Note: The Secret Life of Canada is hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen and is a CBC original podcast independent of The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Canadian legislation has evolved throughout the years with regards to the migration of children (see Immigration Policy). For example, in 1922, the Empire Settlement Act,

passed by the British Parliament and applicable to Canada, allowed for the immigration of unaccompanied “juveniles” between the ages of 14 and 17. In 1925, as a result of three

suicides by “home children,” the Canadian government stopped allowing the entry of unaccompanied minors under the age of 14. In 1946, following the end of Second World War, an

Order-in-Council was issued which allowed Canadian citizens to sponsor their siblings, parents, and orphaned nephews and nieces. This order was expanded in 1947 to allow all legal residents to sponsor their families, including unmarried children.

The age at which an unmarried child can be sponsored has been a contentious point of policy, with the cut off recently changing from under 22 years to under 19 years.

Today, Canada continues to receive child migrants from all over the world. Some immigrate with their families, while others come independently as unaccompanied minors wishing to claim refugee status. For many children, experiences of migration are fraught with family separation, trauma and dislocation.

Experiences of Child Migrants

The United Nations estimates that over 50 million children worldwide have been uprooted by conflicts. Migration can be a very stressful event for children. These stresses can be particularly acute if children have witnessed killings or other traumatic events while fleeing to Canada or when the child is migrating alone. In 2015, over 100,000 unaccompanied minors applied for asylum in 78 countries, a number which tripled since 2014.

As of January 2017, Canada has resettled 40,000 Syrian refugees, including a large number of children of all ages. Many of these children personally witnessed the effects of the ongoing conflict in Syria and some experienced the difficult journey to neighbouring countries, including dangerous escapes at sea. Some, like Alan Kurdi, the three-year-old Syrian boy photographed lying dead on a beach — an image that galvanized Canada’s response, did not survive these journeys. For Syrian children who have arrived in Canada, their experiences have resulted in complex mental health issues such as anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and traumatic memories. However, such traumatic and life-altering experiences are not specific to Syrian children; and child migrants who come to Canada from other countries experience them as well.

Unaccompanied Minors in Canada’s Asylum System

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has long-standing guidelines for offering protection and asylum to children who are arriving alone, referred to as “unaccompanied minors.” As of 2016, globally there are over 100,000 unaccompanied minors, with estimates ranging between 2,000 and 4,000 in Canada.

Canada’s asylum adjudication body, the Immigration and Refugee Board, has its own guidelines on how to proceed when an unaccompanied minor makes a claim for refugee status centered on the best interests of the child. These guidelines recognize that children may have difficulty testifying and recalling traumatic events, and that a designated representative should be assigned as soon as possible to assist the child during the process of claiming refugee status.

Importantly, groups such as the Canadian Council for Refugees argue that the definition of an unaccompanied minor should be broad enough to recognize that even in cases where the child may be accompanied by another relative, such as a 19-year-old sibling, they still require additional supports when settling in Canada without their parents as guardians. Unfortunately, while there are some protections in place, as of 2017, there is no integrated federal strategy on how to deal with separated and unaccompanied child migrants in Canada.

Family Reunification and Separated Children

Prolonged family separation is a serious concern for refugee and immigrant families. Many parents and children are separated for prolonged periods or even indefinitely due to barriers to family reunification. These policies include: barring sponsorship if the sponsoring parent is receiving social assistance; costly and time-consuming DNA testing; excluding family member if they are not declared in original applications for status; a narrow definition of family which exclude non-biological children such as step-children or adopted children.

The Immigration Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) currently imposes a lifetime bar on sponsorship of a family member if an immigration officer did not examine the family member when the sponsor immigrated to Canada. This permanent ban on family class sponsorships is very detrimental to children and refugees are among those most affected by this policy. Refugees who flee their country and arrive in Canada often do so without their children. If parents do not declare their children as part of their asylum process, the child will be barred from entering Canada indefinitely. However, even in instances where the child is declared and refugee parents can then apply to bring their immediate family members to Canada, families are sometimes forced to wait years to be reunited with their children overseas, many of whom remain in danger in their countries without their parents.

In addition, the former Conservative government also changed the age at which a child is no longer considered dependent for the purposes of being able to immigrate to Canada from under 22 to under 19 years old. This policy does not account for children who may be over the age of majority but still dependent on their parents, such as post-secondary students or those with disabilities. However, due to public pressure, the Liberal government announced in late 2016 that it will be changing the age of eligible dependents who may be sponsored back to under 22 years.

Children in Immigration Detention

Under international law, children and youth should not be held in immigration detention. Immigration detention falls under the framework of administrative law, where the person being detained has not committed a crime, but may be being detained for immigration reasons. Canada has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which states that “the best interests of the child” arealways a primary consideration and that detention must be a complete last resort. Canada’s own legislation, the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, affirms that best interests of children in detention must be taken into account.

However, Canada has recently been critiqued domestically and internationally regarding its policies of detaining migrant children. For example, Canada’s immigration detention regime was critiqued at its periodic review by the United Nations Human Rights Committee in the summer of 2015.

Despite these criticisms and knowledge of their legal responsibilities and harms experienced by detained children,the Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) continues to detain children with their families. When families are detained, men and women are separated and children remain with their mother in detention centers. There is very limited access to resources in detention, including regular schooling, social interaction and even outside time for children. Detention of children has proven adverse effects on a child’s mental, physical and emotional well-being, and can compromise their development going forward.

Canadian-born children of migrant parents have also been held by CBSA. While as Canadian citizens they cannot be not officially “detained,” they are considered the “guests” of their detained parents, especially in cases where the parents cannot make alternate care arrangements or they fear family separation. There are a number of cases where Canadian-born children have spent their entire lives while in immigration detention, like Alpha Anawa, who was the “guest” of his mother, Glory Anawa. Their case, along with three others parties, formed the basis of a 2015 court case, which determined that immigration detainees have access to the remedy of habeas corpus, or relief from indefinite detention by the state, at Ontario provincial courts.

In 2016, the Federal Court of Canada also affirmed that the best interests of children must be considered by CBSA when their parents are detained. The case confirms that, in line with international human rights law, Canada must consider the best interests of the child when deciding whether to detain. However, at least 82 children were held in immigration detention in 2015 and early 2016, and the number is potentially much higher, since CBSA does not track Canadian-born children that are detained alongside their parents as “guests.” As of early 2017, Canada has not formally abolished its policies to detain migrant children.

International Adoption

Children may also migrate to Canada by way of being adopted by Canadian parents. International adoption standards are governed by the 1993 Hague Adoption Convention, which was drafted after concerns surfaced about the sale and trafficking of children through inter-country adoptions. Children that are internationally adopted from orphanages may have been displaced by war and conflict, or may have been given up for adoption due to their gender. However, specific country policies regarding international adoptions vary greatly and the process takes on average of two to three years for Canadian parents. There are also restrictions specific to certain countries, for example, banning parents over 40 or same-sex couples from adopting. Special-needs cases and lengthy medical tests and procedures may also deter some parents from adopting internationally. International adoption is also costly, with the whole process costing up to $50,000.

While there is still high demand for international adoptions in Canada, rates have been declining. For example, according to Statistics Canada, between 1999 and 2009, annual rates of internationally adopted children ranged from 1,500 to 2,200 children, for a total of nearly 21,000 children. In 2009, 22 per cent of these children were from China, 12 per cent from the United States, 8 per cent from Ethiopia and Vietnam, and 7 per cent from Haiti. However, only 905 children were adopted in 2014.

This decline may be as a result of stricter international laws governing out-of-country adoptions of children, with countries such as China, Russia and Latin American countries (such as Cuba and Guatemala) placing greater constraints on international couples wishing to adopt children.

Children who migrate experience unique policy and legislative issues in their journeys to Canada. These issues are exacerbated especially when they arrive alone as unaccompanied minors, when they are separated from their families or when they are detained. Many children that have been displaced as a result of war will face significant challenges in settling into their life in Canada, including PTSD and trauma. Children can also experience long wait times when going through the international adoption process, and may have issues with integration when they arrive. However, aside from these challenges, many child migrants grow up to add their richness of experience to the fabric of Canada as their new home.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom