Relief Commission Case Files

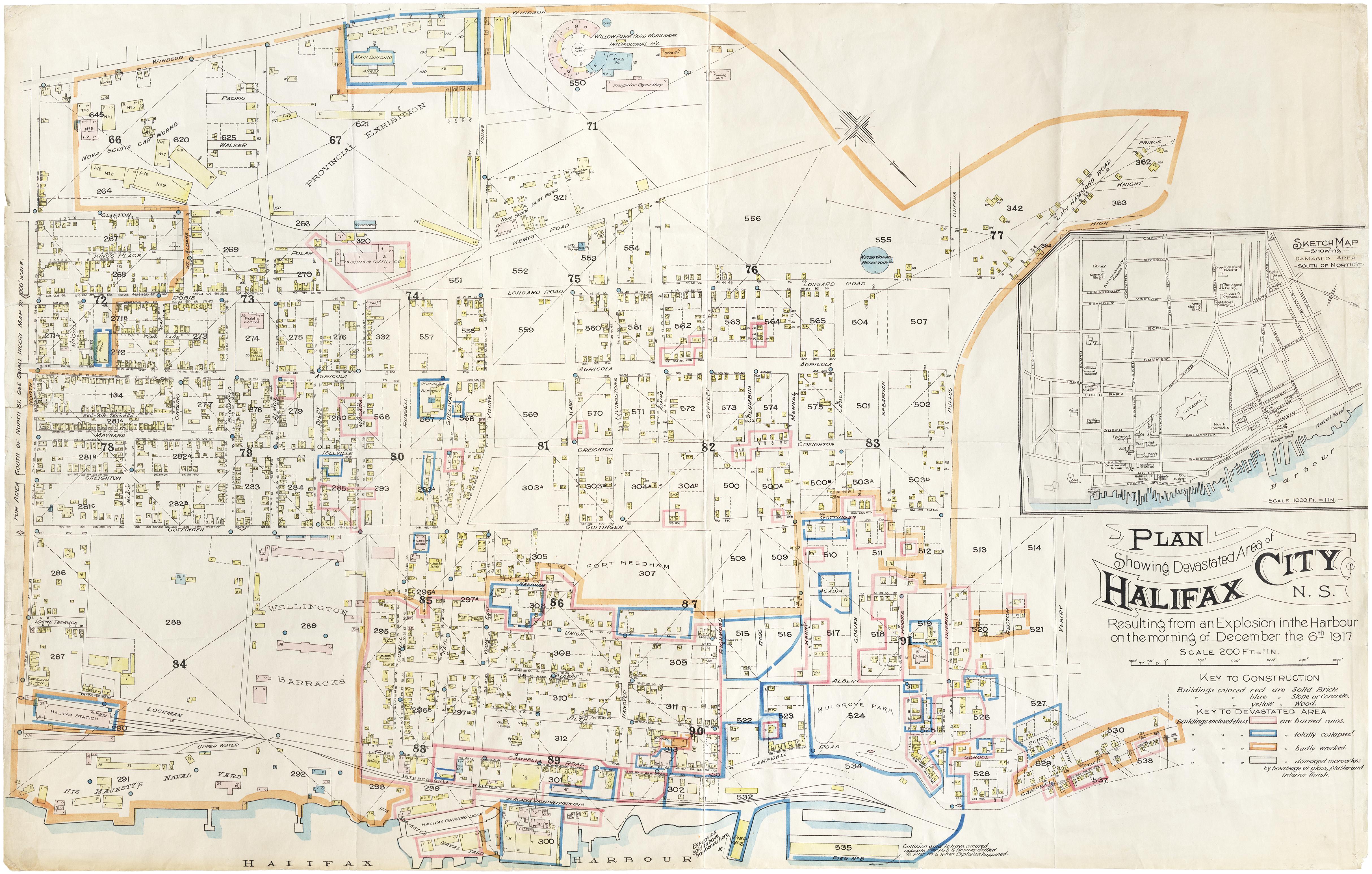

After the Halifax Explosion on 6 December 1917, the Halifax Relief Commission was created by the federal government to help rebuild the city and administer welfare services for the explosion’s victims. Children appear in a great number of the Commission’s archived case files, of which 13 have been chosen by the Champlain Society to provide detailed insight into the experience of being a child, or parent of a child, exposed to the trauma of mass disaster.

Orphaned Children

From the perspective of the Commission, the greatest challenges posed by child victims involved those who had been orphaned. Particularly hard hit was the Johnson family, where husband William died at work on the waterfront while his wife and two of the children were killed in their North End home.

Two other Johnson youngsters survived as orphans. Early in January 1918, their paternal grandmother arrived from Prince Edward Island to claim the youngsters. After a cursory assessment of the elderly woman’s circumstances, the Commission gave her custody, along with the standard pension of $16 per month for each child until they turned 17. Thereafter, they were on their own.

Staff paid considerably more attention to Frances Preece, a teenaged servant hospitalized after having lost an eye in the explosion. The relief staff opposed surrendering Frances back to the Middlemore agency that had brought her from England to Nova Scotia to work as a domestic servant. Insistent that this teen should complete her schooling, the Commission declared Frances to be a de facto orphan and itself assumed the role of guardian.

The explosion death of widower James Sheridan left his two young children without a parent. Following time in an orphanage, the Commission used the promise of pensions to persuade a somewhat reluctant aunt to give them a home.

Similarly, Everett Lavers’s death created a crisis for his disabled teenaged daughter, who had been abandoned by her stepmother. Fortunately, Everett’s unmarried sister volunteered to adopt the child and continue her education, although this positive relationship would be ended prematurely by tuberculosis.

The Commission faced even greater difficulty when dealing with the Carr family. Widow Mary Carr and her youngest child died in the explosion. Six offspring survived, four of them adults and two children. Sibling rivalry led to misappropriation of family assets and then wrangling as the Commission sought to impose fair play on the family.

Children with Physical Wounds

More numerous than orphans were children with significant injuries. Robert Myers, two years old, became partially blind in the explosion and after recuperation was fitted with an artificial eye (see The Halifax Explosion and the CNIB).

While partial loss of sight must have proven traumatic, the explosion sometimes resulted in even more devastating injuries. Such was the case of nine-year-old Roy Cookson, whose fractured skull led to months of hospitalization, only to return home as a chronic invalid. Commission efforts at remediation by way of special diet, drugs, protective clothing, and repeated medical examinations did little good, and Roy died at an early age.

The disaster carved a vicious swathe through the Stokes family, which saw a husband and eldest son killed, the mother and one son totally blinded, another daughter left with just one eye, and her sister without the lower part of one leg. Assisted by an uninjured daughter and pressured by influential friends of the family, the Commission consented to an expensive and protracted program of medical and pension relief.

Roy Hudson, 17, nearly died while aboard a tug attempting to extinguish the fire on the Mont-Blanc. He survived but lost both his feet, which the Commission replaced with prosthetic devices. Offered a large one-time settlement, Roy opted instead for a lifetime pension, combined with repeated replacement of his artificial limbs.

Other Traumas

Having five of their six children killed and then improperly buried, compounded by injuries to the wife that contributed to a miscarriage, proved devastating for the Henneberry family. In an effort to buoy her spirits, the Commission bought Mrs. Henneberry a wig to replace her shorn hair and later granted her a disability allowance until she could once again perform housekeeping duties.

For Jessie Parks, left to supervise seven children while her soldier husband fought in France, the explosion brought a multitude of problems. Two of her offspring suffered injuries severe enough to place them in hospital, while three others temporarily disappeared. Then one of the boys turned truant, prompting the authorities to place him in a reformatory, while several of the girls were sent to an orphanage. The children eventually returned to a badly damaged home that they had to manage while their mother went out to work.

Another form of lasting damage was borne by John Muise Jr., who had to leave college and become chief income earner for the family when his father failed to recover from injuries related to the explosion.

Taken together, these child-related case files suggest a pattern in which the Commission could sometimes soften but never completely overcome distress. Thus, children and their immediate families were doomed to remain among the most poignant victims of the 1917 Halifax disaster.

This article has been condensed and excerpted from The Champlain Society publication "We Harbour no Evil Design": Rehabilitation Efforts after the Halifax Explosion of 1917, edited by David A. Sutherland. Reprinted with permission from The Champlain Society.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom