The first major Canadian coal mining disaster was at Westville, Pictou County, Nova Scotia, on 13 May 1873 after a shot of explosive ignited methane at the coal face. The fire caused a gas explosion, which, fed by coal dust, ripped through the mine and set off further explosions, killing workers and firefighters attempting their rescue. Those untouched by the blast and fireballs were brought down by the carbon monoxide left in the fire’s wake. The mine was sealed to starve the fire of oxygen, and two years passed before the last of 60 bodies were recovered.

The Pictou County coal field was particularly dangerous because the thick, methane-oozing seams made them prone to spontaneous combustion and explosion. Of the coal field’s 676 known mining deaths, 246 were from explosions. Experts considered Stellarton’s Allan mine the world’s most dangerous colliery. In the explosion of 23 January 1918, 88 died, leaving barely a family in the community untouched by the disaster.

From 1866 to 1987, 1,321 fatalities were reported in Cape Breton mines, including 65 in an explosion at New Waterford (25 July 1917), and 16 in Sydney Mines (6 December 1938) when a cable broke, sending a riding rake plummeting. The last explosion (Glace Bay, 24 February 1979) took 12 lives.

At Springhill, Nova Scotia, from 1881 to 1969, 424 persons died in mines, mostly in three explosions. On 21 February 1891, 125 miners were killed in an explosion triggered by a shot that flamed back and ignited gas. On 1 November 1956, six cars from a coal trip being hoisted broke away and crashed into an electric cable. The ensuing flash of electricity lit the coal dust generated by the crash, creating a huge dust explosion that killed 39. The event was notable for the rescue of 88 trapped survivors. On 23 October 1958, a “bump” (i.e., underground earthquake) killed 74 men in mine number two. Miraculously, 12 entombed men were found alive after six days and seven more three days later. They were rescued from levels as deep as 3,960 m — the deepest rescues ever conducted in Canada.

Western Canada

Canada’s worst coal mine disaster occurred on 19 June 1914 at Hillcrest, Alberta. It is believed that a rock fall struck a spark, setting off dust explosions that crippled the ventilating fans and burned away half the mine oxygen. As a result, 189 men died, leaving 130 widows and about 400 children. Also in the Crowsnest Pass, at Coal Creek near Fernie, British Columbia, 128 were killed in a methane explosion on 22 May 1902. Several explosions in this area were caused by lightning.

Canada’s second-deadliest mine disaster occurred in Nanaimo on 3 May, 1887 when 150 perished in an explosion. Vancouver Island knew its fair share of disasters, with such towns as Ladysmith and Cumberland joining Canadian communities like Bellevue and Lethbridge, Alberta, and River Hebert, Thorburn and Inverness, Nova Scotia in the annals of mine disasters in Canada.

Impact

Tragedy was not only in lives lost, but also in families bereft of their breadwinners in a society with little, if any, compensation, and no government-sponsored income security programs. Moreover, many were permanently injured in these accidents, never to work again, while destruction of a mine left miners unemployed.

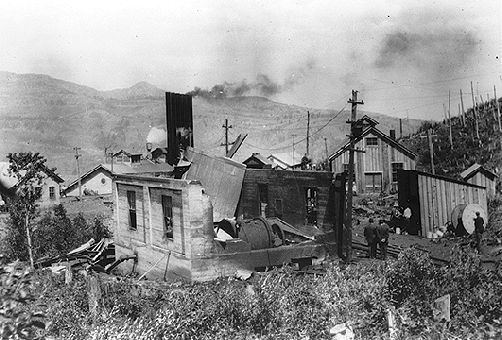

Automation has reduced the workforce in modern collieries. The Westray mine in Plymouth, Nova Scotia, exploded on 9 May 1992, claiming 26 lives — the whole underground shift on duty. It was determined that sparks from the blade of a continuous mining machine exploded methane, which would not have been present with proper monitoring and ventilation. Fuelled by an illegal buildup of coal dust, the blast roared through the mine, wrecking everything in its path. The report of a commission of inquiry damned the negligent operation of the mine and flagrant violations of the Coal Mines Regulation Act. After the explosion, the Westray Families Group and the United Steelworkers successfully lobbied to amend Canada’s Criminal Code to assign criminal liability to organizations for acts of their employees and directors. Bill C-45 came into force on 31 March, 2004.

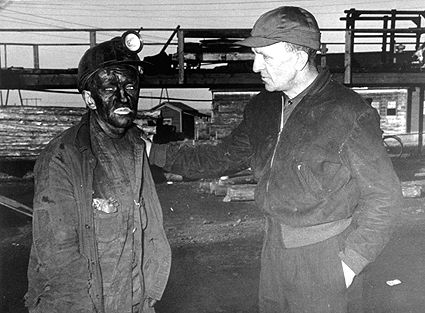

Rescue teams have been specially trained to save miners trapped in gas, fire, explosive, flood or other dangerous conditions. In 1906, the first self-contained breathing apparatus for mine rescue in North America was obtained by Glace Bay collieries. Rescue workers, known as draegermen, were responsible for saving many lives in mine disasters, usually working under precarious conditions and at great risk to their own lives. See also Mining Safety and Health.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom