Fine art is meant to be contemplated and interpreted; decorative art is designed to be used and enjoyed. Nonetheless, there is no sharp boundary between the decorative and the fine arts. Yet for thousands of years, people have fashioned everything from totem poles and shaman’s rattles to elaborately carved stone and ivory knives and harpoons. These items served ritual and practical purposes and carried with them both spiritual and historical meanings. There is no reason to think a useful object cannot also be a bearer of meaning. Contemporary Canadian artists and artisans continue to blur the lines between decorative and fine art.

Distinction Between Fine Art and Decorative Art

For most contemporary art critics, the term “decorative” is pejorative. It implies that a work, though perhaps pretty, lacks content and depth. It is commonly assumed that the decorative arts have two features that are at odds with what we think of as fine art. First, decorative art is typically associated with function (e.g., glasses, plates, bowls, jars, carpets, clothes, etc.). Second, its purpose is to project a style or mood rather than to transmit meaning and incite dialogue.

Nonetheless, there is no sharp boundary between decorative and fine arts. This distinction is largely a modern invention in which art is regarded as something to be experienced, contemplated and appreciated from a neutral distance; never as something to be used for a specific purpose. But this was not always the case. The early Canadian artisans who embellished the churches and cathedrals of 17th century Quebec with decorative stonework and stained glass windows did so with the intention of at once pleasing, instructing, inspiring, and occasionally frightening devout parishioners. (See also Architecture History: The French Colonial Regime.)

For literally thousands of years, Indigenous peoples fashioned everything from totem poles and shaman’s rattles to elaborately carved stone and ivory knives and harpoons. These items served ritual and practical purposes and carried with them both spiritual and historical meanings. In addition, the style and effects employed by contemporary painters, sculptors and photographers are often meant to make their works a pleasure to look at. There is no reason to think a useful object cannot also be a bearer of meaning.

20th Century Decorative Artists

The much celebrated Danish-born Kjeld and Erica Deichmann, whose New Brunswick studio was the subject of two National Film Board documentaries, and Alma and Ernst Lorenzen in Nova Scotia, established the craft in Atlantic Canada. Theo and Susan Harlander, Jimmie and Selma Clennell, Nunzia D’Angelo Zavi and Jarko Zavi, and Konrad Sadowski and Krystyna Sadowska were based in Ontario. Adolf and Louise Schwenk and Herta and Walter Gerz were active on the West Coast. For the most part, their pottery shared a European sensibility favouring figurative decoration hand-painted in Scandinavian hues of browns, greens and blues, and simple functional shapes. The annual Ceramic National Exhibition in Syracuse, New York, was a favourite venue for the first generation of studio potters to exhibit their functional work and enhance their profile.

In Quebec, studio pottery was shaped by Gaëtan Beaudin, who trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Montreal. He founded an important workshop and school in North Hatley in the late 1950s and 1960s. There he taught handmade functional pottery in traditional wood-fired Asian stoneware and raku. In 1973, he abandoned craft and founded his own ceramic tableware manufacturer SIAL II. It synthesized craft and commercial techniques.

During the late 1980s and 1990s, a new emphasis on conceptual thinking was developed, particularly by Quebec ceramists Léopold L. Foulem, Paul Mathieu and Richard Milette. They deconstructed vases, teapots and other tableware using a combination of hand techniques, moulds and found objects, rendering them non-functional to better investigate the specificity of the medium, often with a sense of kitsch and humour. The nomenclature of potter, pot and pottery fell out of fashion, and ceramist, ceramics and vessel became the new vocabulary for better expressing artistic meanings and metaphors. This same period witnessed a maturing of figurative ceramic sculpture, as expressed by Susan Low-Beer and Ann Roberts in Ontario and Kathy Venter in British Columbia.

Contemporary Artists

Contemporary Canadian artists and artisans continue to blur the lines between decorative and fine art. Painter David Bolduc’s lyrical abstractions pay explicit homage to various decorative traditions. Bolduc was an enthusiastic traveller, and in the course of his many journeys he absorbed the design traditions of China, Central Asia, India, and North Africa. In Knossos (1995), for instance, a bright blue flower shape with a swirl inside of it sits in the middle of the canvas against a blazing, deep red ground, orange star-shapes arching down on either side toward two strips of horizon that resemble stands of trees. We know from the painting’s title, which is after a Greek city on the island of Crete thought to be Europe’s oldest city, that the blue alludes to the blue Aegean and the red to the fierce Greek summer sun. But what makes the painting work is the push and pull between the cool blue and the rippling heat of the ground behind it.

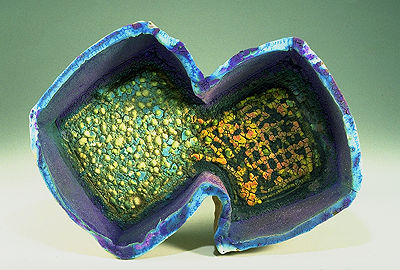

Just as fine artists make free use of decorative effects, contemporary ceramists borrow from the fine arts. Robert Archambeau’s pots, influenced by Asian ceramic traditions, have a simple, elegant, almost archaic nobility that transcends their use. Their surfaces are washed with earth-tones and a hint of glassy blue and green. Archambeau’s pots point toward a way of thinking about life, a mode of living.

Throughout his career, Victor Cicansky has systematically warped the line between traditional ceramics and sculpture, creating works that make use of replicas of the vegetables he grows in his garden in Regina. And Marilyn Levine, one of Canada’s most internationally celebrated ceramists, more or less forgoes function altogether. She uses traditional stoneware to fashion stunningly realistic facsimiles of ordinary objects: a handbag, a suitcase, a jacket hanging from a hook, an old pair of boots.

The debate continues among critics and curators as to whether the medium is art or craft, but less so amongst the new generation of artists. There is far less reverence for skill, as witnessed by the arrival of sloppy craft, articulated by a messy and loose handling of material by artists like Alwyn O’Brien in British Columbia and Linda Sormin in Ontario. For Rory MacDonald in Nova Scotia or Robin Lambert in Alberta, engaging ceramics with the community both in and outside the white cube gallery is a strategy to activate the medium to broader and more diverse audiences. This approach is known as craftivism.

The vessel and the issue of containment — the paradox between positive and negative space — continues to hold interest for many current artists such as Steve Heinemann in Ontario. A keen focus on figurative sculpture and figurines and a predilection for narrative and storytelling marks the field. This can be seen in the work of Janet Macpherson, Lindsay Montgomery, Kate Hyde and Magdolene Dykstra, all from Ontario. Some prefer the immersive theatricality of installations to create a total interactive environment in clay, including such artists as Neil Forrest in Nova Scotia, Amélie Proulx in Québec and Eliza Au in British Columbia.

Also important for reinvigorating the field are artists who did not study ceramics formally at art school but choose to embrace the medium in their practice. Notable examples include Shary Boyle from Ontario, Clint Neufeld in Saskatchewan and Brendan Tang from British Columbia who each follow an individualized approach to making pottery. Throughout these activities, studio pottery endures. Whether it is wood-fired country style stoneware by Robin DuPont in Alberta or urban pastel coloured wheel-thrown porcelain tableware by Thomas Aitken in Ontario, they represent the roots of contemporary ceramics and its lasting relevance.

See also Crafts; Quilt; Folk Art; Printmaking; Inuit Printmaking.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom