Amending the War Measures Act

The War Measures Act was a federal law adopted by Parliament on 22 August 1914, after the beginning of the First World War. It gave broad powers to the Canadian government to maintain security and order during “war, invasion or insurrection.” It was used, controversially, to suspend the civil liberties of people in Canada who were considered “enemy aliens” during both world wars. This led to mass arrests and detentions without charges or trials. (See also: Internment in Canada; Ukrainian Internment in Canada; Internment of Japanese Canadians.)

In 1960, the War Measures Act was amended by the Canadian Bill of Rights, the country’s first federal law to protect human rights and fundamental freedoms. The bill declared that fundamental freedoms of speech, religion, assembly and of the press were to be upheld regardless of “race, national origin, colour, religion or sex.” It also asserted the right to “life, liberty, security of the person and enjoyment of property, and the right not to be deprived thereof except by due process of law.”

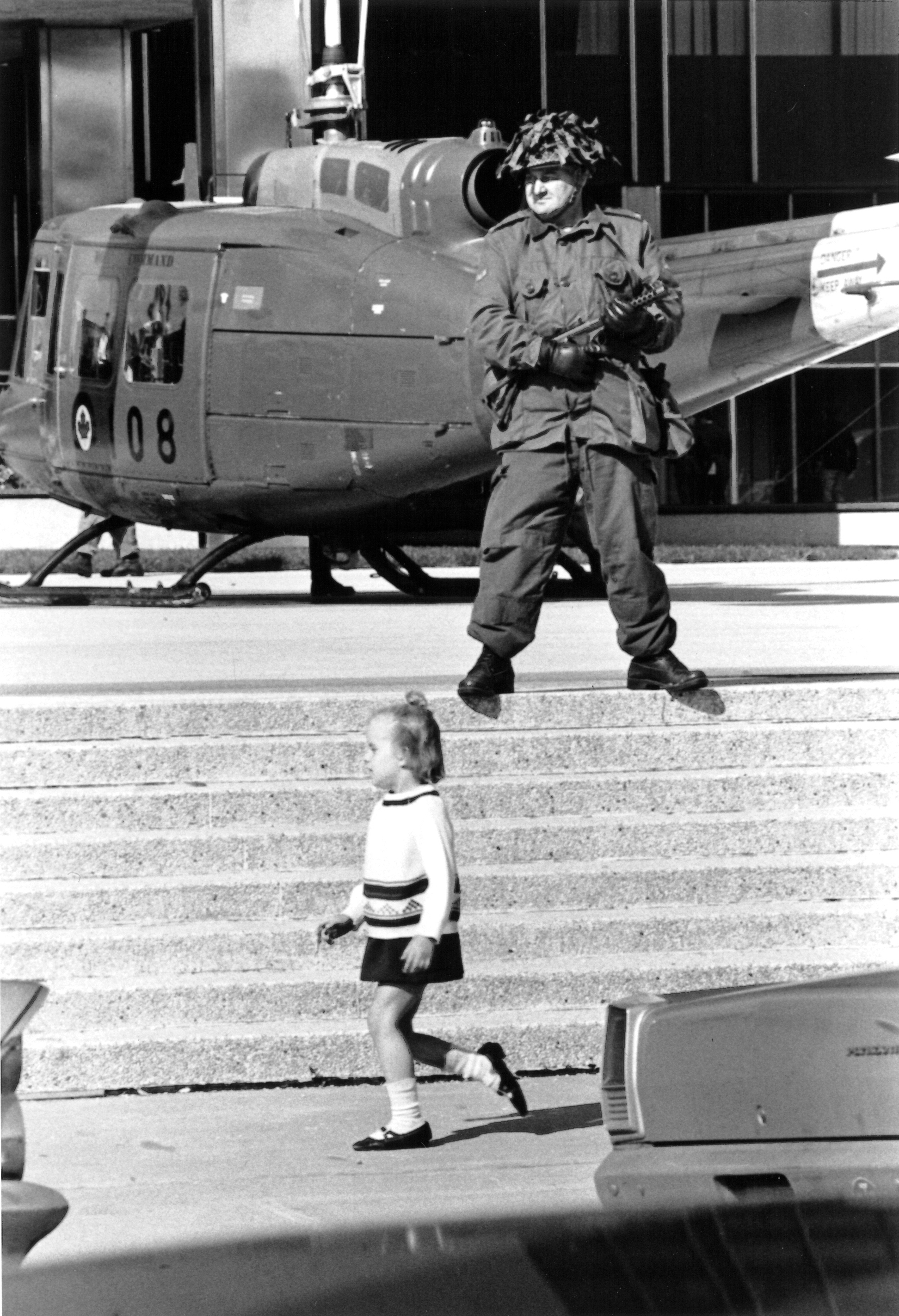

However, Section 2 of the Bill of Rights stated that Parliament could override the rights afforded by the bill by inserting a “notwithstanding” clause in the applicable statute passed by Parliament — such as the War Measures Act. This was done only once, during the 1970 October Crisis in Quebec.

The suspension of civil liberties in Quebec was politically controversial. When the crisis was over, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau pledged to refine and limit the application of the Act in internal crises. However, by the time the final Trudeau government was defeated in 1984, the War Measures Act had not been modified.

Repealing and Replacing the War Measures Act

In the decades following the world wars, Canadians who had been interned and who had their property seized under the provisions of the War Measures Act began lobbying for compensation for and recognition of their wartime treatment. Under Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, the federal government repealed the War Measures Act and replaced it with the Emergencies Act, which received royal assent on 21 July 1988.

The Japanese Canadian redress movement resulted in an official apology from Prime Minister Mulroney on the floor of the House of Commons in 1988. Financial compensation was also given to people affected by the government’s invocation of the War Measures Act. In the case of people interned during the First World War, a community settlement fund was established in 2008 to support commemorative and educational projects about Canada’s first national internment operations.

Characteristics of the Emergencies Act

The Emergencies Act is different from the War Measures Act in some important ways. The Act created more limited and specific powers for the federal government to deal with security emergencies. Under the Emergencies Act, Cabinet orders and regulations must be reviewed by Parliament, meaning the Cabinet cannot act on its own, unlike under the War Measures Act. The Emergencies Act outlines how people affected by government actions during emergencies are to be compensated. It also notes that government actions are subject to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Canadian Bill of Rights.

National Emergency

The Emergencies Act defines a “national emergency” as “an urgent and critical situation of a temporary nature that: a) seriously endangers the lives, health or safety of Canadians and is of such proportions or nature as to exceed the capacity or authority of a province to deal with it; or b) seriously threatens the ability of the Government of Canada to preserve the sovereignty, security and territorial integrity of Canada.”

If a national emergency is declared, the Act prohibits the federal government from detaining, imprisoning or interning Canadian citizens or permanent residents “on the basis of race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.”

Public Welfare Emergency

The Act defines a “public welfare emergency” as one “that is caused by a real or imminent a) fire, flood, drought, storm, earthquake or other natural phenomenon; b) disease in human beings, animals or plants; or c) accident or pollution; and that results or may result in a danger to life or property, social disruption or a breakdown in the flow of essential goods, services or resources, so serious as to be a national emergency.”

If a public welfare emergency is declared, the federal government is required to specify a) the “state of affairs constituting the emergency;” b) the “special temporary measures that the Governor in Council anticipates may be necessary for dealing with the emergency;” and c) the “area of Canada to which the direct effects of the emergency extend.”

Under the Act, a public welfare emergency grants the federal government the right to:

- regulate or prohibit travel “to, from or within any specified area;”

- evacuate people and remove personal property from any specified area, and to make arrangements “for the adequate care and protection of the persons and property;”

- requisition or use property;

- direct any person or “class of persons” to render essential services, with “the provision of reasonable compensation;”

- regulate “the distribution and availability of essential goods, services and resources;”

- authorize and make emergency payments;

- establish emergency shelters and hospitals;

- assess “damage to any works or undertakings and the repair, replacement or restoration thereof;”

- assess damage to the environment;

- impose fines and indictments “for contravention of any order or regulation made under this section.”

If a public welfare emergency is declared, the Act prohibits the federal government from assuming control of any police force that normally falls under the jurisdiction of a municipality or province. The Act also stipulates that a public welfare emergency “expires at the end of ninety days unless the declaration is previously revoked or continued in accordance with this Act.”

Public Order Emergency

The Act defines a “public order emergency” as one that “arises from threats to the security of Canada and that is so serious as to be a national emergency.” The Act also stipulates that “threats to the security of Canada” are to be defined in accordance with section 2 of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act. (See Canadian Security Intelligence Service.)

If a public order emergency is declared, the federal government is required to specify: a) the “state of affairs constituting the emergency;” b) the “special temporary measures that the Governor in Council anticipates may be necessary for dealing with the emergency;” and c) the “area of Canada to which the direct effects of the emergency extend.”

Under the Act, a public order emergency grants the federal government the right to:

- regulate or prohibit “any public assembly that may reasonably be expected to lead to a breach of the peace; travel to, from or within any specified area; or the use of specified property;”

- designate and secure protected places;

- assume control, restoration and maintenance of public utilities and services;

- direct any person or “class of persons” to render essential services, with “the provision of reasonable compensation;”

- impose fines and indictments “for contravention of any order or regulation made under this section.”

The Act specifies that the application of these powers must not interfere with the ability of a province to respond to an emergency of its own. A public order emergency “expires at the end of thirty days unless the declaration is previously revoked or continued in accordance with this Act.”

Other Emergencies and Provisions

The Act lists similar stipulations to be applied in case of an international emergency or a war emergency. It also lists the requirements for proper parliamentary supervision during the application of the Act, and for compensation of people and groups after the application of the Act.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom