Emily “Millie” Carr, painter, writer (born 13 December 1871 in Victoria, BC; died 2 March 1945 in Victoria). Emily Carr was one of the most important Canadian painters of the first half of the 20th century. She was one of the only major female artists of that period in either North America or Europe. Her paintings are bold, surreal and mythical. They have also been criticized for appropriating Indigenous culture. Carr was also an acclaimed author. She wrote Klee Wyck. It is a volume of short stories based on her time with Indigenous people. It won a Governor General's Literary Award in 1941.

This article is a plain-language summary about Emily Carr. If you would like to read about this topic in more depth, please see our full-length entry: Emily Carr.

Early Life

Emily Carr’s parents were British immigrants. They settled in the small town of Victoria, BC. Her father was a successful merchant. Carr was the second-youngest child of nine. She grew up with a brother and four older sisters. It was a strict and orderly household. English manners and values were maintained. Carr enjoyed drawing as a child. But she had no artistic role models growing up.

Carr’s mother died in 1886. Her father died in 1888. (Both died of tuberculosis.) Once she turned 18, Carr convinced her guardians to let her study art at the California School of Design in San Francisco. There she learned the basics of painting. When she returned home three years later, she began painting in watercolour. She also taught art classes for children.

Early Artistic Career

Emily Carr took a study trip to England in 1899. But it did little to advance her art. A lengthy illness kept her there until 1905. She then returned to Victoria.

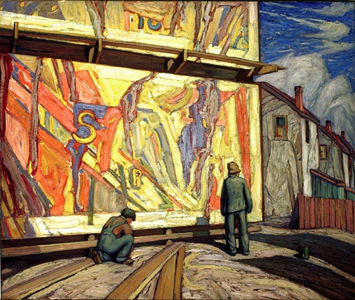

In 1910, she wanted to find out what the new modernist art was all about. She set out with her sister Alice for France. Carr developed her own bold, colourful style of painting. She returned to Victoria in 1912.

Exposure to Indigenous Culture

In 1908, Emily Carr visited several southern Kwakiutl villages. But even before that, she had shown an interest in Indigenous peoples and their culture. At that time, Indigenous culture was thought to be dying. Despite her keen interest in Indigenous culture, Carr shared this attitude.

DID YOU KNOW?

In 1862–63, a smallpox epidemic that began in Victoria wiped out the area’s Indigenous people. Some 14,000 Indigenous people — about half of the population along the Northwest Coast — died. The epidemic left mass gravesites and abandoned villages. (See Smallpox Epidemic in British Columbia.)

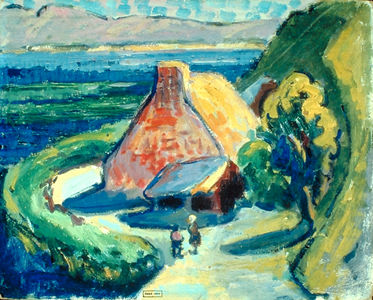

Carr returned from France in the summer of 1912. She then decided to make paintings of Indigenous totem poles. She made a six-week trip to the Queen Charlotte Islands (now Haida Gwaii) and the Skeena River. There she documented the art of the Haida, Gitksan and Tsimshian peoples. Her work on this trip established the two great themes of her painting career. First, the presence of Indigenous cultures of the past. And second, the unique landscape of Canada’s West Coast.

Carr painted in her “French style” for about 10 years. She produced small works that would have been seen as advanced in any part of Canada. By 1913, she had produced a large body of work. But she was discouraged by the lack of encouragement and support. She was unable to make a living selling her art. She built a small apartment in Victoria for income. For the next 15 years, she managed the apartment and painted little.

Career Breakthrough

The period of work that Carr is famous for began when she was 57 years old. Her early work on Indigenous subjects was seen by an ethnologist studying in British Columbia. He brought these paintings to the attention of curators at the National Gallery of Canada. They were holding an exhibition of Northwest Coast Indigenous art. Carr was invited to take part in the exhibition. She attended the opening in November 1927.

It was there that Carr met Lawren Harris and members of the Group of Seven. It was the leading art group in English Canada. They welcomed Carr as an artist of equal stature. Their paintings of the rugged landscape of Northern Ontario impressed Carr greatly. She quickly snapped out of her feelings of isolation and returned to painting.

With Lawren Harris as her mentor, Carr began to paint the bold, surreal canvases for which she is known. These included paintings of totem poles deep in forests, and the sites of abandoned Indigenous villages. After a year or two, Carr left Indigenous subjects to devote herself to nature themes.

From 1928 on, Carr began to receive critical acclaim. Her work was included in major shows at the National Gallery of Canada and the American Federation of Artists in Washington, DC. Her works also began to sell. They never sold enough to improve her financial situation. But she continued to produce a great body of paintings.

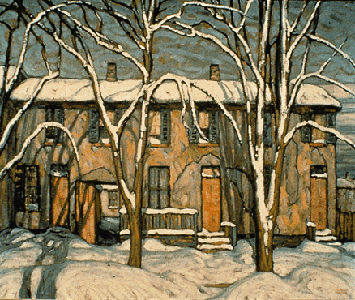

In Carr’s mature paintings, nature is shown to be a furious vortex of organic growth. It is shown with curving shapes that signify constant movement and transformation. By comparison, the human elements — churches, houses, totem poles — seem small and fragile.

Writing Career

In 1937, Emily Carr suffered her first heart attack. Her health and the energy required for painting both declined. She began to devote more time to writing. She had begun to write years earlier, encouraged by CBC executive Ira Dilworth. Carr’s first book, Klee Wyck, is a volume of short stories. It was based on her time with Indigenous people and was published in 1941. That year also marked the end of her painting career.

DID YOU KNOW?

Klee Wyck (“Laughing One”) is the name the Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka) people gave Emily Carr. Her book of the same name is a memoir. It describes in vivid detail the influence that the Indigenous people and culture of the Northwest Coast had on her and her art.

Klee Wyck won a Governor General's Literary Award for non-fiction in 1941. Carr followed it with four other books. Two of them were published after she died. The stories are all autobiographical. They show Carr to be a person of great spirit and individuality. The stories are written in a simple, straightforward style. They quickly won Carr a popular audience. But in the end, it is mainly as a painter that Carr has won critical acclaim.

Recent Exhibitions

In recent decades, Emily Carr’s appeal has stretched beyond Canada. She is now seen as an important 20th-century artist. In 2001–02, she was included alongside Georgia O'Keeffe and Frida Kahlo in an acclaimed touring exhibition called Places of Their Own. It was organized by the McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

In 2012, seven of Carr’s paintings from the collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery were displayed at dOCUMENTA (13). It is an important art showcase in Kassel, Germany. In 2020, Emily Carr: Fresh Seeing — French Modernism and the West Coast was exhibited at the Royal BC Museum in Victoria. It included 67 works. It was the largest ever showing of Carr’s Paris paintings.

Also in 2020, the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in New Brunswick showcased more than 50 of Carr’s paintings. In 2022, some of her landscapes were presented as part of Uninvited: Canadian Women Artists in the Modern Moment. It focused on the work of notable female artists of the 1920s–40s who were excluded by the artistic establishment of the day. The show started at the McMichael gallery and was later held at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Legacy

More than 150 years after her birth, Emily Carr is a Canadian icon. She has also been harshly criticized for her appropriation of Indigenous culture. But her interest in Northwest Coast Indigenous cultures coincided with the start of a rising tide of awareness of issues concerning Indigenous peoples. Carr’s passionate view of nature also coincided with a growing awareness of environmental issues.

Carr struggled against the obstacles facing women of her day to become an artist of stunning originality and strength. This made her a favourite of the women's movement. But it was her painterly skill and vision that allowed her to give form to a Northwest mythos that was distilled in her imagination. Even though we may have never visited the West Coast, we feel we know it through her art.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom