History and Development

On 13 February 1947, the Imperial Oil Company found crude oil at its Leduc #1 well, about 15 km south of Edmonton, Alberta (see Striking Oil in Leduc). The Leduc well began Alberta’s oil industry. However, finding crude oil was the first step; it still needed to be transported to refineries to turn it into usable products (see Petroleum Exploration and Production).

On 30 April 1949, Imperial Oil created the Interprovincial Pipe Line Company (IPL). Its first pipeline cost $73 million to construct and, in October 1950, began transporting crude oil from Edmonton to Superior, Wisconsin. Within a year, the company had transported 30.6 million barrels of oil. In 1953, a new pipeline, Line 5, was constructed from Superior to refineries in Sarnia, Ontario, allowing Alberta oil to supply Ontario’s growing manufacturing base. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, IPL and its American subsidiary, the Lakehead Pipe Line Company, built more pipelines that connected additional American cities including Buffalo, Chicago and Detroit.

The company also expanded in Canada. In 1972, IPL pipelines were transporting an over 1 million barrels of crude oil per day across North America. In June 1976, after an expenditure of $247 million, a pipeline transported Alberta oil to Montréal. In April 1985, IPL pipelines connected the oilfields at Norman Wells, Northwest Territories, to its pipelines in Zama, Alberta, and, through that junction, across Canada and into the United States.

In 1988, IPL changed its name to Interhome Energy Inc. The company expanded in 1996 when it purchased Consumers’ Gas. It was soon transporting natural gas from its sources and distributing it directly to businesses and homes. About this time, the company’s name changed to IPL Energy Inc.

The company’s operations also expanded internationally with the acquisition of a pipeline in Colombia. By the summer of 1996, its 829 km OCENSA pipeline was transporting crude oil from the Cusiana and Cupiagua fields in central Colombia to its west coast.

Enbridge Created

In 1998, IPL changed its name to Enbridge Inc. The name refers to what the company does by linking the words energy and bridge. Shortly afterward, Enbridge became involved with the exploitation of the Athabasca oil sands in northern Alberta, near Fort McMurray. The difficult process of extracting crude oil from the area by processing it from the rock and soil in which it rests began in 1964. By the 1990s, the oil sands promised to be North America’s largest depository of crude oil. By 1999, Enbridge had built one long-haul pipeline connecting the oil sands to its existing pipelines in Edmonton and Hardisty, Alberta, and, through them, to other parts of Canada and to the United States.

In 1999, Enbridge developed a natural gas distribution network into New Brunswick. Its 2001 purchase of Houston’s Midcoast Energy Resources was followed by a further expansion of its American natural gas distribution network. In 2005, Enbridge acquired Shell Gas Transmission LLC, including ownership interests in 11 natural gas pipelines in 5 offshore Gulf of Mexicopipeline corridors.

Beginning in 2001, Enbridge began to invest in sources of renewable energy. It invested in Saskatchewan’s SunBridge wind power project and by 2012 was involved with 10 wind farms, 4 solar energy operations, 4 waste heat recovery programs, and a geothermal energy project — all representing a $5-billion investment. At the same time, Enbridge altered many of its practices with the goal of becoming more environmentally responsible (see Environment). It was subsequently listed as one of the world’s most sustainable companies eight years in a row. In 2016, American magazine Newsweek ranked Enbridge the world’s 12th most sustainable corporation.

Controversy

While pipelines play an essential role in the transportation of crude oil and natural gas from their sources to refineries and then to customers, they are controversial because they sometimes break, resulting in leaks onto land and into water. Several Enbridge lines have suffered spills. In 2017, the Great Lakes Region of the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) stated that Enbridge’s aging Line 5 — linking Superior, Wisconsin, and Sarnia, Ontario — had experienced 29 leaks between 1968 and 2015, resulting in the spilling of over 1 million gallons of oil and gas liquids in 64 years. The NWF insisted that the leaks threatened the water supply of more than 40 million people (see Water Pollution).

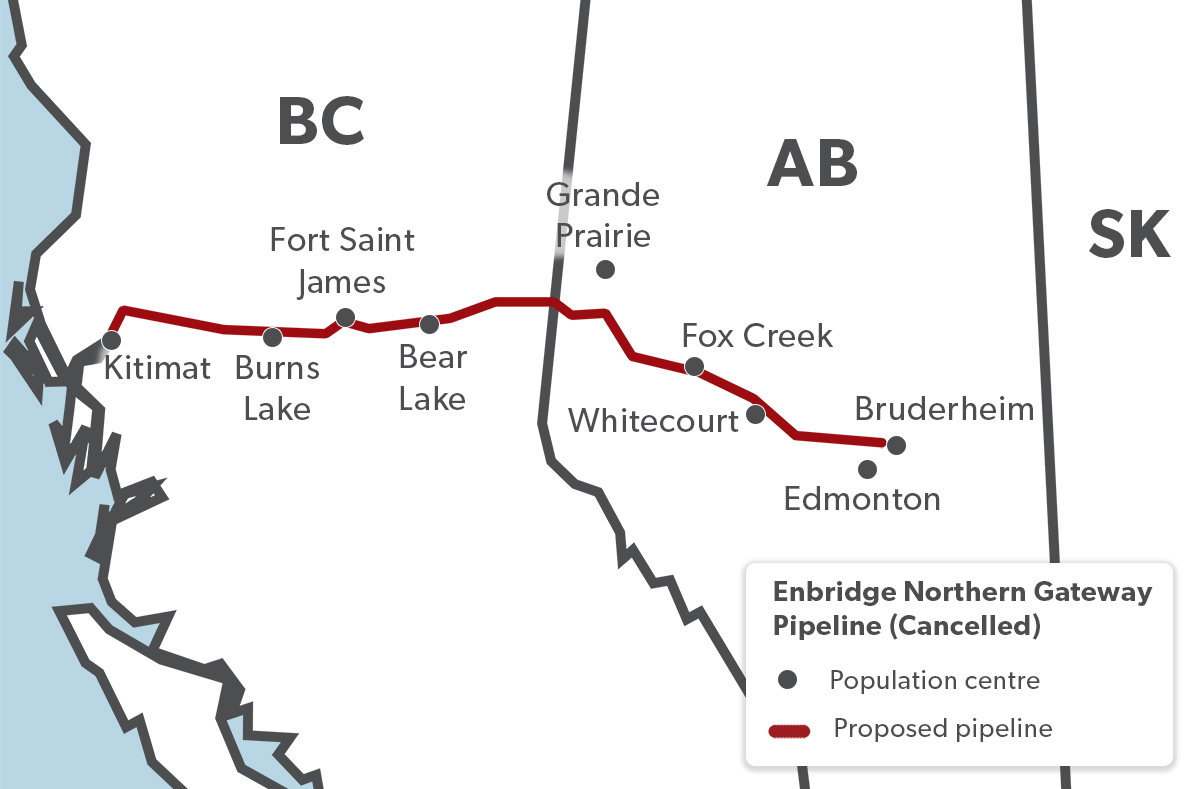

In 2005, Enbridge signed a deal with PetroChina stipulating that it would purchase oil from Alberta’s oil sands. A 1,172 km pipeline would bring the crude from northern Alberta to the small, northern British Columbia port of Kitimat. The pipeline’s construction would cost $6.6 billion and be called the Northern Gateway. The project was immediately opposed by environmental groups who worried about spills along the route and in the harbour and along the coast. Several First Nations communities objected to the pipeline crossing their land (see Environmental and Conservation Movements).

Meanwhile, Enbridge initiated government approval processes to rebuild and expand its aging 1,659 km Line 3 that took crude oil from Hardisty, Alberta, to Superior, Wisconsin. The $7.5-billion project proposed to fix problems, render the pipeline safer and increase its volume to allow the transportation of 760,000 barrels a day. Objections were raised by environmental protection groups and communities through which the pipeline ran, including many Indigenous communities. (See Line 3 Pipeline Replacement Program.)

The Northern Gateway and Line 3 proposals led to fiery public hearings and long, complex submissions to the Canadian government’s National Energy Board, the body responsible for issuing the necessary licences to proceed. Enbridge admitted, with respect to both projects, that there is always “residual risk” but promised to take all necessary precautions to mitigate them. It pledged, for example, to use tethered tugboats to pull big oil tankers out of the Kitimat harbour and through the Douglas Channel, to employ new radar and other navigation aids, and to enforce strict rules about the quality of ships that would be allowed to transport the oil.

In July 2010, Enbridge’s pipeline in Marshall Township, Michigan, ruptured, dumping 20,000 barrels of oil in the Kalamazoo River watershed. The US National Transportation Safety Board investigated the spill and accused Enbridge of lax safety standards, made worse by the fact that the company’s monitoring stations had been between shifts when the rupture happened so that no one was watching the line. Enbridge promised to make changes, but the damage was done to the environment, to people of the area and to the company’s reputation.

In November 2016, the Canadian government announced that it would not approve the Northern Gateway project. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said that he was approving a proposal put forth by Enbridge’s competitor, Kinder Morgan Energy Partners, to build a pipeline from Alberta to a bigger and more southern British Columbia port. Trudeau said of Enbridge’s Northern Gateway: “It has become clear that this project is not in the best interest of the local affected communities, including Indigenous peoples.” Trudeau also announced that the government approved Enbridge’s Line 3 rebuild.

Continued Growth

In September 2016, Enbridge purchased Spectra Energy Corporation of Houston, Texas, for $37 billion. The move increased Enbridge’s value to $166 billion and made it North America’s largest energy infrastructure company. Enbridge was restructured with its natural gas pipeline business run from Houston, its liquid pipeline business from Edmonton and its headquarters remaining in Calgary. The move also meant that Enbridge laid off about 1,000 employees. The layoffs, potential for tax savings, and capacity for more growth in Canada and the United States increased Enbridge’s stock price and dividends for investors.

In November 2017, Enbridge filed an application with the Ontario Energy Board to amalgamate with Union Gas. Enbridge stated that the merger of the two natural gas distribution companies would allow a more efficient distribution to customers. Critics said it would create a monopoly that would allow Enbridge too much power to control distribution and prices.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom