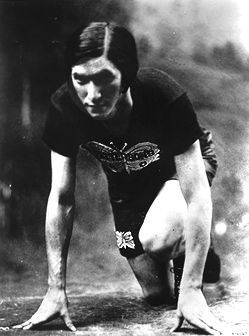

Fanny "Bobbie " Rosenfeld, track and field athlete, sportswriter (born 28 December 1904 in Ekaterinoslav, Russia [now Dnipro, Ukraine]; died 13 November 1969 in Toronto, ON). An exceptional athlete who excelled in many sports, including basketball, hockey and softball, Rosenfeld is best known for her medal-winning performances on the track at the 1928 Olympic Summer Games in Amsterdam. After retiring from competition, she became a well-known sportswriter — her column “Sports Reel” ran for 20 years in The Globe and Mail. Through her athletic accomplishments and her sports journalism, Rosenfeld helped to promote and defend women’s sports, and was a role model for many sports-minded women, particularly those from the working class.

Early Life

Fanny Rosenfeld was born in 1904 in Katrinosalov, Russia, now Dnipro, Ukraine. She was the second child for Max and Sarah, after son Maurice (1902). In 1905, while Fanny was still an infant, the family moved to Canada and settled in Barrie, where they already had family. While in Barrie, three more daughters were born: Gertrude (1906), Mary (1907) and Ethel (1919). Max worked first as an iron-dealer and then as a peddler — a common occupation for Jewish immigrants in the early 20th century — and eventually established a used-goods business. In many ways, the Rosenfelds were a typical working/lower-middle-class immigrant family. Their eldest daughter, however, would be anything but typical.

Even as a young girl, Fanny excelled at sports. In a 1957 article in The Globe and Mail, she recalled winning her first race at age nine while attending a picnic; she and her sister Gertrude placed first and second in the 50-yard dash and were rewarded with a free lunch. Her talents weren’t limited to the track. Fanny also played basketball, softball, lacrosse, ice hockey and tennis growing up. While at Barrie Collegiate Institute, she starred on the school basketball team as well as on the track. It was during high school that she received the nickname “Bobbie,” in reference to her short, bobbed hair.

Toronto Sports Star

In 1922, when Rosenfeld was 18, her family moved to Toronto, purchasing a single-family house on Markham Street near Lippincott, in an area then noted for its concentration of lower-middle class Jewish families. According to Rosenfeld, she deliberately failed two courses at Barrie Collegiate so that she could attend Harbord Collegiate Institute in Toronto, which reportedly had a much stronger athletic program.

Rosenfeld quickly made her mark on the Toronto sports scene. In March 1922, the Globe reported that she was a member of the Toronto Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) hockey team. At the end of the year, she again appeared in a Globe article about the basketball team of the Young Women’s Hebrew Association (YWHA). The YWHA team won city and provincial championships, and even made it to the national championships, where they were defeated by the renowned Edmonton Grads.

After graduating from Harbord Collegiate in 1923, Rosenfeld was hired as a stenographer at Patterson Chocolate Factory. Patterson, like other companies at the time, promoted sport and recreation among its female employees and sponsored a number of sports teams. Rosenfeld played on many of those teams, and was captain of the Patterson hockey team that dominated women’s hockey in Ontario. She also played on the Hind & Dauche softball team, one of the strongest in the Toronto Sunnyside women’s leagues. In addition, Rosenfeld continued to play for the YWHA hockey and basketball teams, and was a member of the Toronto Ladies Athletic Club; she also won the city’s 1924 grass court tennis championship for women. By the mid-1920s, her name was appearing regularly in the city’s sporting pages.

Track and Field

While she excelled in many sports, Rosenfeld is best known for her achievements in track and field. Rosenfeld had run competitively from a young age, but until 1923 was better known for her success in team sports. That summer, she played an exhibition softball game in Beaverton, Ontario, as a member of the Hind & Dauche team. The game was part of a sporting carnival, which also included a track meet. Her teammates convinced her to enter the 100-yard race, which she won. Although she didn’t realize it at first, she had beaten the top Canadian sprinter, Rosa Grosse.

Not long after, Rosenfeld began training with Grosse, Grace Conacher and Myrtle Cook under coach Walter R. Knox. The four Canadian runners would thrill crowds later that year, on 8 September 1923 — the first time women competed at the annual Athletic Day at the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE). In the 100-yard race, Rosenfeld beat Grosse for the win. In the relay, the Canadian foursome defeated the more experienced team from the United States, the Chicago Flyers. In contrast to the Flyers, who wore proper running shorts and shirts, Rosenfeld raced in her brother’s swimming shorts, her father’s socks and her white Hind & Dauche softball jersey.

The CNE competition made Rosenfeld a star. Her rivalry with Grosse continued and became a feature of the annual CNE Athletic Day: Grosse won the 100-yard sprint in 1924, while Rosenfeld recaptured it in 1925, setting a new world record. The same summer, she dominated the first Ontario women’s track and field championship, held at Varsity Stadium in Toronto and hosted by the Toronto Ladies’ Athletic Club. Rosenfeld won five events (shot put, discus, 220-yard dash, long jump and low hurdles) and placed second in two events (javelin and 100-yard dash), breaking the world record in the 220-yard dash.

The Matchless Six and the 1928 Olympics

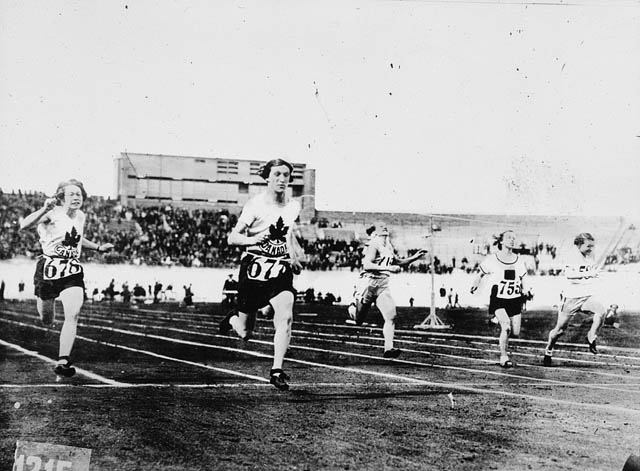

One of the “Matchless Six,” the talented Rosenfeld became a national and international star at the 1928 Olympic Summer Games in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. This was the first time that women were allowed to compete in track and field at the Olympic Games (although the Canadian member of the International Amateur Athletic Federation, Dr. Arthur S. Lamb, voted against women’s participation). It was also the first time Canada sent a women’s team to the Olympics. Five events were open to women in track and field: the 100 m race, 800 m race, 4x100 m relay, high jump and discus. The “Matchless Six” —Rosenfeld, Jean Thompson, Ethel Smith, Myrtle Cook, Ethel Catherwood and Jane Bell — would make their mark on the world stage; Rosenfeld and Smith won two medals each, including a gold medal as part of the relay team, while Catherwood took gold in the high jump.

Rosenfeld, who excelled on both the track and the field, had been chosen for the 100 m race and the discus event. However, as both events were held on the same day, she was only entered for the track event. The race was delayed due to a number of false starts, which left Canadian favourite Myrtle Cook disqualified and in tears. Mid-way through the race, American Elizabeth (Betty) Robinson was in the lead; however, Rosenfeld caught up and at the finish it was difficult to tell who had won. Although there was some disagreement among the judges, the gold medal was awarded to Robinson. Canada mounted an official protest, but it was dismissed. Rosenfeld would have to be satisfied with silver, while teammate Ethel Smith took the bronze.

Rosenfeld next competed in the 800 m event. Although she had not trained for the race, women’s team manager Alexandrine Gibb asked her to run to provide support for teammate Jean Thompson, who had injured her leg and was nervous about the competition. Although Thompson had the lead for a while, she faded and was passed by three other runners. When Rosenfeld caught up to her, she remained with her teammate, encouraging her to the finish and letting her take fourth (Rosenfeld finished fifth). Her team spirit drew high praise, with Gibb remarking that, “In the annals of women’s athletics, there is no finer deed than this.”

Rosenfeld also won a gold medal at the Games, as lead runner in the 4x100 m relay. The other runners were Smith, Bell and Cook. The Canadians took an early lead, and set a world record time in the event. Teammate Ethel Catherwood (the “Saskatoon Lily”) won another gold for Canada in the high jump.

Upon their return from Amsterdam, the Olympic athletes were paraded through Toronto, cheered on by about 200,000 spectators. According to Rosenfeld, it was “a thrill you will never forget!”

A New Career in Sports Journalism

After the 1928 Olympics, Fanny “Bobbie” Rosenfeld returned to her busy sports schedule. However, in September 1929 she was struck by a severe bout of arthritis; she spent eight months in bed and another year on crutches. By 1931, though, she was back playing softball, and, in 1932, was voted the top women’s hockey player in Ontario.

In May 1932, Rosenfeld began a new career as a sports journalist with the Montreal Daily Herald. Although the job only lasted about four months, she was very active during her time in Montréal. In addition to her writing, Rosenfeld played softball and helped establish the Provincial Women’s Softball Union of Québec, serving as its first president.

The return of arthritis in 1933, however, ended her athletic career for good. Rosenfeld remained active in the sports world, coaching the women’s track and field team at the 1934 British Empire Games in London, England. She was also manager of the Lakeside Langleys, a Toronto softball team, and served on the executives of the women’s provincial hockey and softball associations.

In 1936, Rosenfeld joined The Globe and Mail sports department and her first column appeared in 1937. Known originally as “Femmes Sports Reel” and then “Feminine Sports Reel,” it eventually became simply “Sports Reel,” the name it kept until 1957, when the column ended. “Sports Reel” covered local, national and international sport — both men’s and women’s. Through her column, Rosenfeld promoted and defended women’s sports; in particular, she argued against criticisms that athletic activity made women unfeminine. In response to characterizations of “Amazonian women” and “muscle molls,” Rosenfeld emphasized the attractiveness of female athletes, their marriages and children.

She was also known for her wit and sense of humour. In the July 1933 issue of Chatelaine magazine, Rosenfeld defended women athletes in the article, “Girls are in Sports for Good.” She was responding to a previous article in the magazine that had been written by sportswriter Andy Lytle of the Vancouver Sun. According to Lyle, women should not participate in vigorous sports: “In nearly twenty years as an observer and commentator in athletics I have yet to see a young woman come even reasonably close to the standard set by the average male at rigorous play. It isn’t reasonable to expect that she should. Nature did not cast her in the mannish mold.” Rosenfeld’s response was characteristic:

Athletic Maids, to arms! Andy Lytle beware! We are taking up the sword, and high time it is, in defense of our so-called athletic bodies to give the lie to those pen flourishers who depict us not as paragons of feminine physique, beauty and health, but rather as Amazons and ugly ducklings — all because we have become sport-minded and have chosen to delve so wholeheartedly into competitive sport.

She also defended herself, as well as other women athletes, against detractors of her own sex. In her 22 October 1948 column in The Globe and Mail, Rosenfeld responded to a criticism from a reader:

Every once in so often you let the readers have their say. After all, they pay the shot, such as it is. I will first lead with my chin by showing you the letter of Mrs. J. Richards, though it is mussed up on account of I accidentally stamped on it a couple of times. Mrs. Richards scoffs at women using first names intended for men. She wants I should call myself Fanny yet? Sorry ma’am. They call me Bobbie and I don’t intend to change it. Matter of fact, women with men’s names, in my sober opinion, are more confident than those with feminine names.

In 1957, “Sports Reel” came to a close, and from 1957 to 1966, Rosenfeld ran the promotion department at the newspaper, retiring due to illness. She died in November 1969 and was buried in Lambton Mills Cemetery in Toronto.

Significance

Fanny “Bobbie” Rosenfeld was an exceptional athlete in what many historians consider a “golden age of women’s sports in Canada.” Winner of two Olympic medals and one of the first Canadian women to compete at the Games, she excelled in numerous sports, including athletics (track and field), basketball, hockey and softball. Rosenfeld’s success and popularity helped pave the way for women’s sport — one of the “Modern Women” of the interwar period, her achievements challenged social norms and assumptions about women’s abilities, and she became a role model for young women, particularly those from the working class.

As a journalist, Rosenfeld played a crucial role in defending and promoting women’s sport in Canada. She was not alone. Of the Canadian women involved in the 1928 Olympic Summer Games, three became regular sports columnists at major newspapers. While Rosenfeld’s Globe and Mail column “Sports Reel” ran for 20 years, Alexandrine Gibb wrote for the Toronto Star for 30 years and Myrtle Cook spent 40 years at the Montreal Star. Other pioneers in women’s sport, such as Mabel Ray, Patricia Page, Phyllis Griffiths and Ruth Wilson, also wrote articles and columns in Canadian newspapers.

Honours

- Canada’s Female Athlete of the Half-Century (1950)

- Inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame (1955)

- Canadian Press establishes Bobbie Rosenfeld Award for Female Athlete of the Year (1978)

- Inducted into International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame (1982)

- Bobbie Rosenfeld Park dedicated in Toronto (1991)

- Canada Post issues stamp featuring Rosenfeld (1996)

- Inducted into Ontario Sports Hall of Fame (1996)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom