The Fédération was involved across all spheres affecting women and transformed their relations with government and society. The Fédération initiated major reforms in three major aspects of Québec life: political, social and economic. The extension of voting rights revolutionized women’s ability to participate in political life, while changes to the Civil Code granted them new prerogatives. Calls for pensions for mothers, including single mothers, created the opportunity for women to have a say in family policy, thereby paving the way for the welfare state, while the professionalization of women’s jobs in “caring-based” fields radically changed their relationship with paid work.

Founding

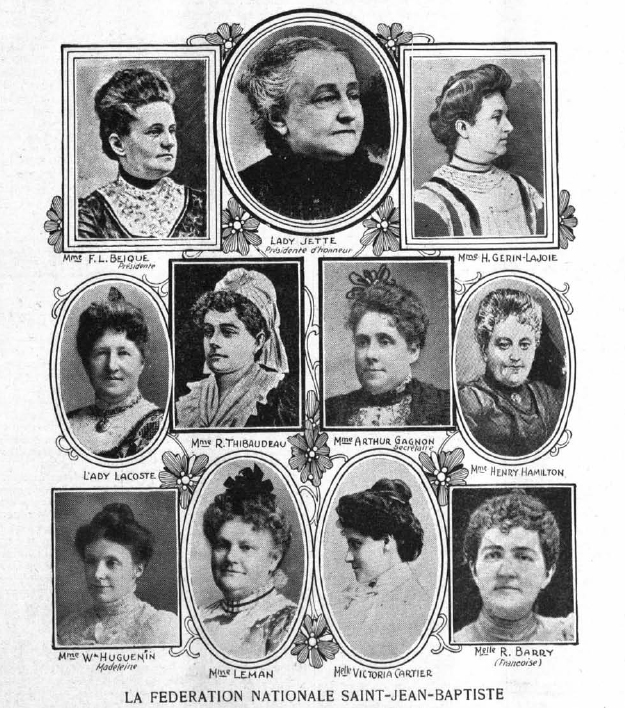

Closely tied to the leading feminist organizations in English-speaking Canada, particularly the National Council of Women of Canada (NCWC), and influenced by the views of the Social Gospel movement it promoted, the Fédération was an offshoot of the Montréal Local Council of Women (MLCW), which was involved in philanthropy, hygiene and education. In 1902, French Catholic activists gradually began leaving the NCWC and the MLCW to “preserve their religious beliefs and their ethnicity,” as a result of pressure from the clergy, which recommended creating faith-based organizations for women similar to those that existed in France. Looking to band together with Catholic French-Canadian women from poor communities, the ladies auxiliary of the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste, became the organizational committee of the Fédération des femmes canadiennes-françaises et catholiques in 1906. Embracing the nationalist ideals of the Société, the new organization also received support from the Archbishop of Montréal, Mgr Bruchési. The Fédération nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste was thus established in 1907, modelled upon the MLCW but with more of a Catholic focus.

As in the MLCW, charity, education and economic action (particularly with respect to women’s employment and professional associations) formed the centrepiece of the FNSJB’s 22 affiliated associations, coordinated through special and standing committees, with the goal of creating a female elite. Despite having split from the Anglo-Protestant feminists of the MCLW, the FNSJB continued to work with the latter on joint initiatives for several years. The support initially received from the Catholic Church was not seen as being in conflict with the central focus of rallying French-Canadian women, whom the Fédération sought to defend against religious and civil authorities.

Political and Civic Action

Drawing on influences from both France and the United States, and from Protestantism as well as Catholicism, the Fédération’s efforts in favour of women’s suffrage caused quite a controversy. French-Canadian women had had the right to vote federally since 1918, but could not yet vote provincially in Québec (they did not gain that right until 1940).

Support for Suffrage

The Fédération’s first years were marked by its support for the suffrage movement at the federal level. In Québec, the clergy and political parties opposed women’s right to vote, so the Fédération had to adapt its stance. Conservative Catholics weren’t wholly against women’s suffrage—they encouraged women’s voting at the federal level, considering it a means to offset what they saw as the detrimental effects of Protestant women being allowed to vote across Canada, but they fervently opposed it at the provincial level and did everything in their power to stop it.

Stressing the traditional idea of women as the “pillars of survival of the French-Canadian nation,” nationalist leaders such as Henri Bourassa considered this role to be incompatible with political involvement. Arguments against women’s suffrage at the provincial level included the idea that women’s right to vote at the federal level was not as significant as their right to vote provincially, and that women in Québec had no desire to insert themselves into the turmoil of the era’s provincial politics.

This line of thinking is precisely what the Fédération and its leaders challenged and tried to reverse for many years. For them, a woman’s maternal role did not imprison her within the family, but rather represented an extension of her responsibilities in public and civic life. The FNSJB refined the maternalist argument to justify its support for suffrage, which would “extend beyond the home, where she is truly queen, the beneficent action of a woman, her spirit of union and conciliation, her love of justice and peace.” In 1922, Marie Gérin-Lajoie and the chair of the Montréal chapter of the NCWC, Anna Lyman, founded and co-chaired the Provincial Committee for Women’s Suffrage (PCWS), giving the FNSJB a central role in Québec’s French Catholic suffragist movement.

However, the Archbishop of Québec, Paul-Eugène Roy, along with Cardinal Bégin, supported by prominent nationalists like Henri Bourassa, formally opposed the creation of this committee. The condemnation of women’s suffrage by religious authorities prompted Gérin-Lajoie to travel to Rome to obtain pontifical directives. At the International Union of Catholic Women’s Leagues, held in Rome in May 1922, Gérin-Lajoie, accompanied by FNSJB secretary Georgette LeMoyne, hoped to find support. She was bitterly disappointed. At the end of its proceedings, the commission that dealt with educating women about their civic duties, in which Gérin-Lajoie had participated, issued recommendations only, rather than taking a firm stance. The three recommendations were not in themselves contrary to women’s involvement in politics. The second recommendation advocated, in particular, “moral, religious and civic education that would make [women] capable, when need be, of this calling.” However, the third recommendation stipulated that all new actions concerning women’s suffrage required prior approval from local episcopal authorities.

The failure in Rome in May 1922 and the anti-suffragist campaign led by the most conservative members of the clergy and their supporters within the government seriously undermined the suffragist movement in Québec. Fierce debate pitted the youngest members of the Fédération, such as Idola Saint-Jean and Thérèse Casgrain—who favoured a feminism rooted in equal rights, with less respect for Catholic morals and authorities—against Gérin-Lajoie’s generation. Gérin-Lajoie had to face a certain resolution from Saint-Jean and Casgrain, two of her colleagues within the PCWS, calling for candidates in future federal elections to publicly take a stance on women’s suffrage. These thinly veiled criticisms of her efforts as well as her own feelings of failure prompted Marie Gérin-Lajoie to resign as chair of the PCWS in late 1922. In 1927, Thérèse Casgrain took over and transformed the PCWS, which became the League for Women’s Rights in 1929. She travelled to Québec City in 1927 to call for a reform of the Charter of Montréal, which would give married women the vote. Two years later, she made a similar request (for the right to vote to be granted to married women who owned land and had separate property) to Montréal city councillors. As for Marie Gérin-Lajoie, she succeeded in creating a civics course at the Université de Montréal to teach and train a female elite that would take up the fight for feminist causes.

The FNSJB continued to call for the right to vote until the late 1930s. At that time, two very different women were at the forefront of the Québec suffragist movement: Thérèse Casgrain and Idola Saint-Jean. Both had gained experience through the FNSJB and were its successors. Casgrain took up advocacy in the partisan arena by persuading the Québec Liberal Party to adopt a resolution to support women’s suffrage. The Liberals’ election victory in 1939 led to women receiving the right to vote provincially in April 1940.

The matter of women’s civic rights emerged during the suffragist movement. Marie Gérin-Lajoie, who chaired the civic affairs committee, created by the FNSJB in 1913, proposed no more and no less than to reform the Civil Code to ensure an equal place for women in civil and family matters—she argued that women should be able to administer shared property, and that married women who work should be able to manage their own earnings and inherit assets when their husbands die without a will. Furthermore, she recommended that movable and immovable property under the regime of community of property could not be disposed of by a woman’s husband if it did not benefit their joint children. Civil Code reform began in 1927. The Fédération wasn’t looking to abolish marital authority; rather, it sought to grant women new rights based on their marital responsibilities. Its goal was not to destroy the community of property system but rather to modernize French laws in Québec.

The report of the Civil Code reform committee, adopted in 1930, was a victory for the moderate line the FNSJB supported. The report incorporated many of the Fédération’s proposals regarding the regime of community of property, even though the hierarchy of power within the family and women’s submission to their husbands were not abolished. The Code was amended in 1931 to establish the concept of reserved property, which allowed a woman to manage her own earnings and the goods she acquired with them. Women also obtained the right to authenticate wills, and a husband’s ability to dispose of marital assets was restricted.

Social Action

The Fédération’s social action focused on social intervention, services, and lobbying on behalf of vulnerable women. The social agenda of the Fédération, its committees, and its affiliates consisted mainly of fighting against infant mortality and for family well-being (temperance, women’s employment, children’s education, hygiene, home economics). The temperance movement introduced the FNSJB to activism practices (forming committees, seeking out alliances, coordinating with other organizations, creating action plans and petitions). It proved to be ideal terrain in which to advocate for the activists’ vision of the family and female values. This type of maternalist feminism was separate from the familialism of the Church, which limited women to their role within the family, and gave rise to government maternalism—the beginnings of Québec’s welfare state.

Care for Mothers and Children

In 1896, the MLCW formed a health committee whose directors, Mrs. Thibaudeau and Mrs. Learmont, organized public lectures and bilingual classes on infant hygiene for working-class women (800 women attended the first lecture). They also distributed pamphlets on caring for sick children to mothers. Milk dispensaries, which first appeared in the early 1900s, also became places to educate and spread awareness of hygienic practices. The FNSJB also created its own hygiene committee, alongside a temperance committee that fought against alcoholism and smoking. In 1910, the FNSJB helped create Gouttes de lait, a network of milk stations that promoted breastfeeding and taught principles of hygiene. In 1913, it went on to establish a committee to combat infant mortality.

The founding in 1907 of the Hôpital Sainte-Justine, dedicated specifically to the care of women and children, was one of the FNSJB’s most significant achievements. Justine Lacoste-Beaubien, Marie Gérin-Lajoie’s sister, was the backbone of the project, rallying her entire network to carry it out. She collaborated with the Daughters of Wisdom, a religious congregation, which trained nurses and took responsibility for the internal management of the hospital. The hospital relied on volunteers, which included a body of elite nurses numbering up to 170 per year in good years. Through a committee established in 1914, the volunteers worked at the hospital dispensary, prepared children for medical examinations, recorded weights and temperatures in medical files, trained in outpatient specialty clinics, performed secretarial work and gave vaccinations in prevention campaigns. They worked as nurses until the early 1960s, when registered nurses became professionalized.

In 1926, the FNSJB, led by its hospital visitors’ committee, created a school for disabled children. Having noticed that many Catholic children attended the School for Crippled Children at the Children’s Memorial Hospital (which had been open since 1916 to Protestant, Catholic and Jewish children), the Ladies’ Committee wanted its long-term patients to be able to be educated in a French Catholic school. When the school opened, volunteers taught 50 hospitalized children, caring for them and teaching them technical skills so that they would eventually be able to earn a living. In 1932, the school came under the control of the Montréal Catholic School Commission.

The final component in the range of services offered by the FNSJB was maternal assistance—home care for needy mothers. Created in 1912, this service was provided by volunteer doctors, who established an office with six doctors and a nursing area staffed by female volunteers and childcare assistants in 1913. Medical and nursing care were available at dispensaries as well as at home.

The knowledge the Fédération gained in offering these various services to vulnerable women led the organization to become involved in political representation calling for the protection of mothers, including single mothers. It advocated establishing a pension program for needy mothers. In stating its case to the Québec Social Insurance Commission, chaired by Édouard Montpetit, the FNSJB proposed a compromise between services already provided to mothers by private charities (particularly Catholic ones) and government involvement.

The Fédération believed that integrating the experience and skills of private organizations into the new insurance system was fundamental. It openly opposed the conservative leanings of the clergy, which was not willing to relinquish its monopoly over providing assistance to families. The Fédération helped to publicly challenge this monopoly by working with the Commission. Additionally, by referencing laws adopted in the United States, France and several other Canadian provinces to argue for the individuation of women and children within the family, the FNSJB proposed a secular model for family affairs in the early 1900s. It promoted home support for families, all the while highlighting the complex roles of mothers, including single mothers.

This social action program was the basis for numerous projects that the FNSJB led with the government during the regular “pilgrimages” that its leaders made to Québec City. But while Anglo-Protestant activists found allies among the educated elite, the Fédération faced many obstacles. Because its activities affected the health and welfare sectors, which were largely controlled by religious communities and the Church, it had to adapt its demands to appear more reformist than reformer. In the early 1920s, its project to establish a general registry of the poor who received assistance in the city of Montréal was met with hostility from the Société de Saint-Vincent de Paul, which considered that to be its responsibility.

Women’s Employment

With regard to women’s employment, the Fédération was mainly concerned with paid work and the Women’s Minimum Wage Commission. In 1914, the Fédération set up an employment assistance committee, which provided work for unemployed women as well as emergency assistance. Despite hostile attitudes towards married women working, the FNSJB continued to further the cause of women who had no choice but to work. Marie Gérin-Lajoie met privately with the federal and provincial labour ministers to inform them about the professional associations’ concerns. In 1919, the Québec government adopted a law instituting a minimum wage for women. The FNSJB made efforts to have one of its members represent it on the Women’s Minimum Wage Commission. It was finally successful in 1935 with the appointment of Laura Robert to the Commission.

The Fédération’s social action can be divided into two main periods. In the first period, from 1907 to 1930, the FNSJB’s social campaigns for women and mothers were achieved through offering services to support them. Its actions were characterized by compassion and charity towards vulnerable members of its community; more generally, it also offered intermediary services, operating between charities and the free market. Throughout its second period, from 1930 to 1950, with the professionalization of major female professions well underway, the Fédération had a narrower focus. With most services now within the purview of the government and its public policies, the Fédération turned to publicizing new public (or private) assistance services.

The FNSJB was successful in bringing about the shift from the family ideals upheld by the clergy (familialist) towards a feminist vision requiring government intervention (maternalist). Women were seen in a new light in a variety of positions and roles. Mothers were viewed as individuals—whether married or single, needy or well-off—in need of professional health and social assistance, even as they all continued to work for the well-being of their families. In this process of reimagining family ideals, the status of women changed significantly and their role was recognized and valued.

The Fédération’s activities over the years show the journey of these women, who, through a sort of secular apostolate, asserted their relative autonomy in the face of the all-powerful Catholic Church, all the while forming a close alliance with the provincial government. The reforms to the social and civic status of women that the organization helped to achieve signalled and contributed to Québec’s gradual secularization during the first half of the 20th century.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom