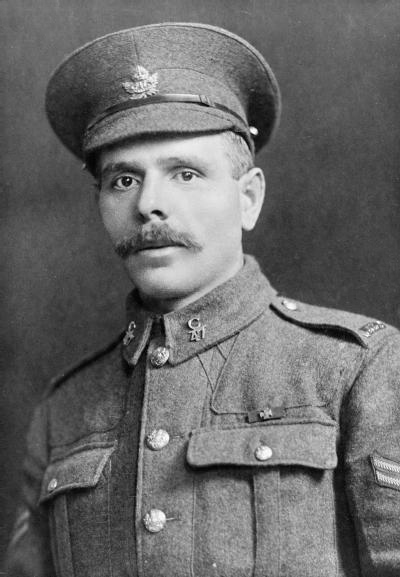

Filip Konowal, Ukrainian immigrant, Great War soldier, Victoria Cross recipient for valour at the Battle for Hill 70, patron of Branch #360 of The Royal Canadian Legion in Toronto, Parliament Hill janitor (born 25 March 1887 in Kutkiw, Ukraine; died 3 June 1959 in Ottawa, Ontario).

Early Years and Immigration to Canada

Born in the Ukrainian village of Kutkiw on 25 March 1887, just east of the Zbruch river separating Ukrainian lands occupied by the Austro-Hungarian empire from those within Tsarist Russia, Filip Konowal was officially identified as “Russian” upon his arrival in Canada, even though he considered himself a Ukrainian of the Greek (Ukrainian) Catholic faith.

Ironically, being “Russian” meant Konowal was not categorized an “enemy alien” during Canada’s first national internment operations of 1914–1920, the fate of thousands who came from the western Ukrainian regions of Galicia and Bukovyna. So Konowal was spared the state-sanctioned indignities they suffered, not because of anything they had done wrong but only because of who they were, where they had come from. Konowal’s status also meant he could volunteer for the Canadian Expeditionary Force without having to lie about who he was, a tactic employed by the many “Austrian” Ukrainians who did enlist.

Like most immigrants in the pre-First World War period, Konowal hoped to find work, eventually to return home with savings. A married man, who had worked in his father Myron’s stone quarry and served in the Tsarist army as a bayonet instructor, Konowal left his wife, Anna, and their daughter Maria behind. Arriving in Vancouver from Vladivostok in April 1913, he was a lumberjack in British Columbia before moving for similar work in the Ottawa valley.

Konowal volunteered to serve with Ottawa’s 77th Infantry Battalion (The Governor General's Foot Guards) on 12 July 1915. Deemed fit for service, he sailed for England in June 1916 and went on to France later that summer as a member of the CEF’s 47th Battalion (Royal Westminster Regiment). He was made an acting corporal effective from 6 April 1917.

First World War

Konowal fought during the Battle of the Somme in late 1916 and the following year served with distinction at the Battle of Vimy Ridge, leading a squad of Japanese Canadian soldiers to help capture the strategic position known as “the Pimple.” Only months later, in August 1917, he fought with exceptional bravery at the Battle for Hill 70, for which he would earn the Victoria Cross. On 21 August, Konowal was grievously injured at Hill 70 with gunshot wounds to the face, jaw, and neck. He was evacuated to Britain where, after recovering from his wounds, he was posted to assist the Military Attaché at the Russian Embassy in London, with the rank of acting sergeant.

Konowal, now a corporal, officially transferred over to the Canadian Forestry Corps before returning to Canada on 10 September 1918. From there he deployed with the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force, sailing to Vladivostok in October 1918, perhaps hoping to return to Ukraine. He was eventually posted in Omsk, Siberia, with the Allied liaison group at Admiral Alexander Kolchak's White Russian HQ. The failure of this anti-Bolshevik intervention (see Canadian intervention in the Russian Civil War), however, saw Konowal returning to Canada on 20 June 1919. He would never see his family again. Eventually, Konowal remarried, making a new family with a French Canadian widow, Juliette Leduc-Auger and her two sons, Roland and Albert. Honourably discharged at Kingston on 4 July 1919, Konowal had served Canada as a soldier for nearly four years.

Only Ukrainian Canadian Recipient of Victoria Cross

What particularly distinguished Corporal Konowal’s wartime record was his valour in August 1917 during the Battle for Hill 70, near Lens, France. According to the London Gazette (1917), Acting/Corporal Filip Konowal received the Victoria Cross:

For most conspicuous bravery and leadership when in charge of a section in attack. His section had the difficult task of mopping up cellars, craters and machine-gun emplacements. Under his able direction all resistance was overcome successfully, and heavy casualties inflicted on the enemy. In one cellar he himself bayonetted three enemy and attacked single-handed seven others in a crater, killing them all.

On reaching the objective, a machine-gun was holding up the right flank, causing many casualties. Cpl. Konowal rushed forward and entered the emplacement, killed the crew, and brought the gun back to our lines.

The next day he again attacked single-handed another machine-gun emplacement, killed three of the crew, and destroyed the gun and emplacement with explosives.

This non-commissioned officer alone killed at least sixteen of the enemy, and during the two days' actual fighting carried on continuously his good work until severely wounded.

King George V personally awarded Konowal the VC on 15 October 1917, saying: “Your exploit is one of the most daring and heroic in the history of my army. For this, accept my thanks.”

A Troubled Postwar Life

However, Konowal’s postwar life was troubled. On 19 July 1919 he led the first postwar Peace Parade through the streets of Ottawa to Parliament Hill. The next day he killed Wasyl Artich, in Hull, Québec, reportedly after Artich attacked Konowal’s friend, Leonti Diedek. Found “not guilty” by reason of insanity, Konowal was confined in Montréal's Saint-Jean-de-Dieu Hospital, an asylum he shared with the French Canadian poet, Émile Nelligan. Following Soviet inquiries in August 1926, possibly seeking Konowal’s deportation, he was spirited away to another facility, near Bordeaux, Québec. Finally released in 1928, just before the Great Depression, Konowal was homeless and destitute.

Thanks to another VC recipient, Major Milton Fowler Gregg (Sergeant-at-Arms at the House of Commons), Konowal got work as a junior caretaker on Parliament Hill, humble yet welcome employment during the Great Depression. Spotted washing floors by Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, he was reassigned as the special custodian for Room No. 16, the Prime Minister's Office, a post he held until his death on 3 June 1959, aged 72. Konowal was buried by his regiment from St. John the Baptist Ukrainian Catholic Church with full military honours, in Lot 502, Section A at the Notre-Dame Cemetery in Ottawa, resting not far from Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier. Konowal’s wife Juliette was buried beside him on 3 March 1987.

Before he died, Konowal gave an interview to the Ottawa Citizen in 1956, saying he was at peace with his work as a parliamentary janitor: “I mopped up overseas with a rifle, and here I must mop up with a mop.” He also revealed something about the circumstances surrounding his bravery at Hill 70: “I was so fed up standing in the trench with water to my waist that I said the hell with it and started after the German army. My captain tried to shoot me because he figured I was deserting.”

Made the honourary patron of Branch #360 of The Royal Canadian Legion in 1953, Konowal was able to travel to England in June 1956, joining over 300 other VC recipients to mark the award’s centennial, an event hosted by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and the British Prime Minister, Anthony Eden. A photograph shows him sitting amongst many other VCs, front and centre, a hero among heroes.

Konowal’s Recognition and Legacy

Following his death, Konowal’s Victoria Cross and other medals were entrusted to F/Lt G.R. Bohdan Panchuk, a Royal Canadian Air Force veteran of the Second World War and leading member of the Ukrainian Canadian Veterans Association. Acquired by the Canadian War Museum in 1969, the VC was stolen in the 1970s, not recovered until April 2004, when Iain Stewart alerted Dr. Lubomyr Luciuk that it had resurfaced at auction, resulting in a timely seizure by the RCMP. Konowal’s VC is now the focal point of a permanent exhibit at the Canadian War Museum, ceremoniously unveiled on 23 August 2004.

Other efforts to recognize Konowal as the only Ukrainian Canadian recipient of the Victoria Cross included the replacement, on 6 December 1996, of his simple grave marker with a more appropriate cemetery headstone, an effort spearheaded by Ron Sorobey and Ottawa’s Ukrainian Canadian community. Trilingual bronze historical markers were placed in Ottawa’s Cartier Square Armoury (15 July 1996), in Toronto at Branch #360’s Queen Street West building (21 August 1996) and on the outside of the Drill Hall of the Royal Westminster Regiment, in New Westminster, British Columbia (5 April 1997). Deplorably, metal thieves stole the Toronto and New Westminster plaques.

Additionally, Konowal was recognized on a cairn at the Ukrainian Village (Selo Ukraina) near Dauphin, Manitoba (August 1997), with a sculpture in his village (2000), and with a bas-relief near Lens, France (2005), initiatives supported by Branch #360 and the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association under the chairmanship of John B. Gregorovich. In August 2017, a memorial will be unveiled near Loos, France, marking the 100th anniversary of the Battle for Hill 70. There could be no more fitting place for Konowal’s valour to be remembered.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom