Lillian Clarke, 15, worked late at the hotel in Frank on April 28, so her employer offered her a room for the night. It was the first time the young girl remained away from home overnight. Lillian's mother, Amelia, had never trusted the hotel's previous owners and would never let her eldest child stay overnight, no matter how late she worked. But the hotel had new owners, people Amelia trusted, and so Lillian settled in for the night. Amelia Clark could not have known that her trust in Lillian's new employers would save the girl's life.

On April 29, 1903, at 4:10 am, in 90 seconds, 82 million tonnes of limestone sheered off the east face of Turtle Mountain and roared down into Crowsnest Pass. The avalanche took with it a coalmine entrance, two kilometres of railway, two ranches and part of Frank, NWT (now Alberta). Of the town's approximately 600 inhabitants, nearly 100 were in the path of the avalanche, which took an estimated 70 lives, though the exact toll will never be known. There may have been people in the area unknown to those who tallied the dead. There were 23 survivors, mostly children.

The Blackfoot and Kutenai people knew Turtle Mountain as "the mountain that moves." Their stories say they wouldn't camp near it. It was named Turtle Mountain by rancher Louis Garnett, who saw in the mountain a turtle's face, with the shell rising up behind.

|

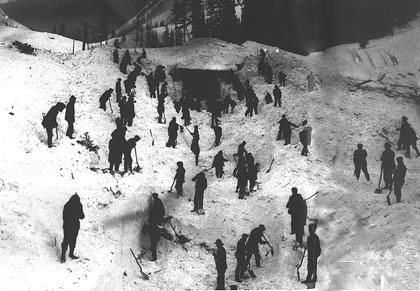

| Twenty-three men, women and children were rescued from the rubble, but at least 70 others died in the sudden disaster. |

The 2000 metre high mountain was thrust up from the Rocky Mountains 70 to 80 million years ago, overriding structurally weaker deposits of limestone and coal. Additional movement cracked the inverted "V" of the mountain peak, creating a conduit for water, opening fissures and gaps where water could settle and then, upon freezing, expand to create internal pressure. Mining further compromised the unstable mountain.

There was more snow than usual during the winter of 1902-03. April was unusually warm, with snowmelt and rain running into the mountain fissures before the weather turned cold again. On April 28th, the water in the mountain froze and the mountain that moves literally reached its breaking point.

In the aftermath of the slide, stories of survival were miraculous, and have generated at least one urban myth. Anyone who has heard of the Frank Slide has heard of the baby girl, the only survivor, found on the boulder. That story is untrue, but it is loosely grounded in fact. Three little girls survived the slide. Fernie Watkins was found in the debris. Fifteen-month old Marion Leitch was thrown from her house and found in a pile of hay, the one most likely to be the "boulder baby." Gladys Ennis, 27 months old, was found in the mud by her mother Lucy, who saved her baby's life by clearing the mud out of her nose and throat. Gladys was the last survivor of the slide when she died in 1995 in Bellevue, Washington.

Lillian Clark was not the only person to escape the disaster by being away from home, but hers may be the most tragic story. Lillian's mother and six siblings died in the slide. Her father, Alfred, was working in the mine that night but stopped for lunch around 4:00. He and another miner were outside the mine when the deadly avalanche struck. The rest of their crew, though trapped in the mine, was able to dig out safely.

Twelve bodies were pulled from the rubble in the days following the slide. The mine was re-opened within weeks and the buried section of railway was rebuilt. The town was moved and life was restored. A road was built through the slide in 1906 and during road improvements in 1922 a construction crew found the skeletal remains of seven people in the rubble. They were believed to be the Clark family, Lillian's mother and brothers and sisters.

Today, the towns of Frank and Hillcrest lie in the shadow of the mountain that continues to move. The sheered mountain and a vast field of rubble are reminders of Canada's biggest rockslide.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom