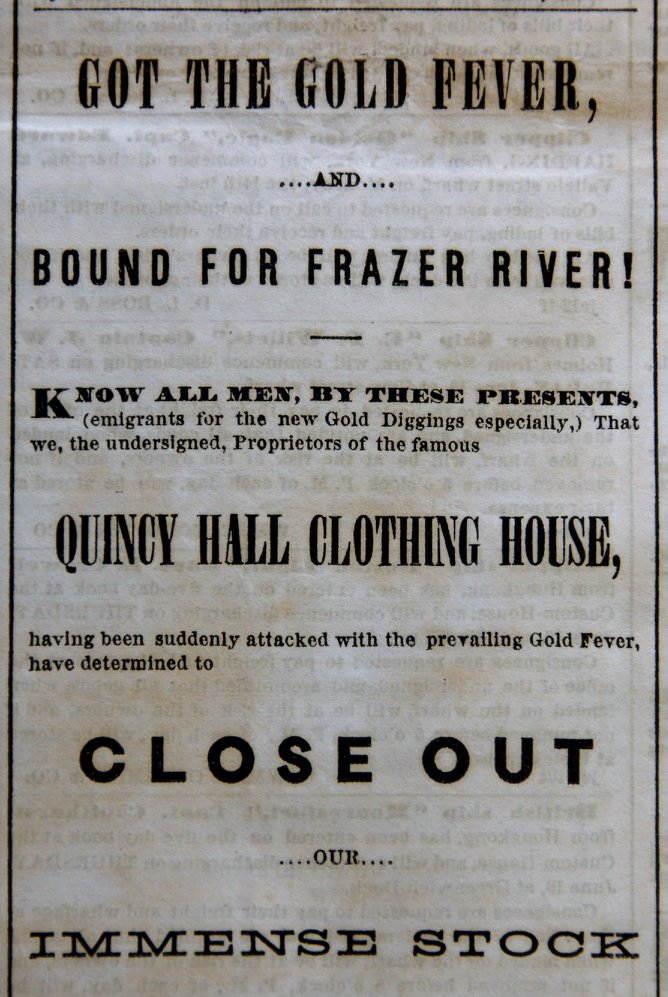

An 1858 advertisement from a San Francisco newspaper claimed that merchants had succumbed to Fraser River “gold fever.”

Background: Fraser River Gold Rush

The Fraser Canyon War was triggered by the Fraser River Gold Rush, which saw thousands of men from the United States stream north into the heart of the Nlaka’pamux peoples’ territory in search of gold in the spring and summer of 1858. Earlier that year, in March, newspapers in Washington and Oregon printed reports of gold discoveries on the Fraser River. When newspapers in California picked up the story, a gold frenzy took hold of San Francisco’s population, triggering a sudden mass migration of between 30,000 and 100,000 miners by land and sea, bound for the Fraser River.

Sir James Douglas, the governor of the fledgling British Colony of Vancouver Island and chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) territories encompassing the Fraser River, fretted the arrival of the miners. He feared they would snatch all the gold for themselves and convince the United States government to annex the mainland of what would become the province of British Columbia. Douglas understood that British authority over the Fraser River region was too limited to enforce any kind of law and order. As he wrote to British Prime Minister Edward Stanley on 19 May 1858: “I am now convinced that it is utterly impossible, through any means within our power, to close the gold districts against the entrance of foreigners, as long as gold is found in abundance, in which case the country will soon be over-run.”

Douglas also believed that the miners would provoke a bloody military conflict with the Nlaka’pamux and surrounding Indigenous communities. He expressed these concerns in a letter to his superiors in London, England, on 15 June 1858, saying: “It will require I fear the nicest tact to avoid a disastrous Indian war.” However, the British could not respond fast enough to restrict the miners’ entrance into the country. By June 1858, thousands of miners from the United States had already made their way to the lower reaches of the Fraser River.

Travelling by boat up the Fraser River past Fort Langley, American miners (mostly of European descent, though some were Hawaiian, African-American and Chinese) funnelled into the narrow lower reaches of the Fraser Canyon. At the end of an arduous journey, and hungering to strike it rich, they congregated at the small HBC fur-trading post of Fort Yale, just downriver from Nlaka’pamux territory.

Initial Attacks

As the summer wore on, miners disrupted Nlaka’pamux communities. Some of the men committed acts of sexual violence against Nlaka’pamux women, euphemistically referred to in a letter by an HBC official as “insulting there [sic] women.” The men mined gold without consulting Nlaka’pamux community leaders for permission, and threatened violence when challenged. Most critically, they disrupted the Nlaka’pamux salmon fishery, a critical economic activity that took place at the end of each summer, by occupying fishing sites and diverting many rivers, creeks and lakes to wash gravel through mining sluices. In the process, they ruined crucial spawning grounds, jeopardizing the future of the salmon fishery.

In response to the escalating violence, Britain made a proclamation on 2 August, laying claim to the Fraser River area as part of the Crown Colony of British Columbia. Politicians believed this would solidify British authority over the region, which was previously only a district, and help secure the region’s gold wealth under British control. Named as the first governor of the colony, Sir James Douglas had already been busy trying to maintain order in the area. He had ordered a gunboat to patrol the mouth of the Fraser River and to demand licences from miners trying to make their way to the goldfields. Still, Douglas had little to no military capability to assert Crown sovereignty over the mainland. The Nlaka’pamux and their allies — the Secwepemc (Shuswap), Sylix (Okanagan) and others — could not count on British colonial authorities on far away Vancouver Island to prevent violence and resource grabbing (see also Interior Salish First Nations).

Faced with a sudden mass invasion of foreigners who were disrupting their communities in unprecedented ways, some members of the Nlaka’pamux nation took up arms to defend themselves. In doing so, they provoked thousands of miners into armed conflict.

“Noon on the Fraser” from The New Eldorado or British Columbia by Kinahan Cornwallis, 1858.

War Breaks Out

Sometime before 14 July, two French miners were found dead near Fort Yale. Some miners believed they had been killed by the Nlaka’pamux and consequently formed a military company to exact revenge. On 9 August 1858, an already tense situation between miners and the Nlaka’pamux people erupted into war. Jason Allard, the son of an HBC trader stationed at Fort Yale, wrote that “troops started for vengeance, in military formation, the stars and stripes at their head.” Departing at Fort Yale, they marched upriver and fought the Nlaka’pamux.

It is unclear exactly how many Nlaka’pamux non-combatants were killed by the American company. Between 9 and 17 August, they killed upwards of 36 people, five of whom were chiefs. They wounded many others and took three prisoners. Retreating downriver, the company burned five Nlaka’pamux villages to the ground. According to one observer, the miners “just killed everything, men, women and children.”

War Intensifies

As the miners retreated to Fort Yale, rumours of Nlaka’pamux attacks upriver spread wildly amongst the miners, stirring them into a frenzy. The miners’ belief that groups of Nlaka’pamux upriver were plotting against them can in part be explained by a common racist stereotype of the 19th century frontier, which was that Indigenous people were treacherous and war-like. Perceiving themselves under coordinated attack, and fearful they would lose access to the goldfields, the miners formed themselves into military companies and readied for more conflict.

One of these companies of several hundred men at Yale was led by Captain Henry Snyder, a miner and newspaper correspondent for the San Francisco Bulletin. Snyder advocated for securing access to the goldfields by marching upriver and holding a peace council with Nlaka’pamux communities. On 18 August, Snyder and his party departed Fort Yale for Kumsheen (a.k.a. Camchin, now Lytton, British Columbia), the geographic and political centre of the Nlaka’pamux world.

The confluence of the Fraser and Thompson Rivers at Kumsheen (Lytton, BC).

A few miles upriver, Snyder and his company encountered two additional companies of American miners who were preparing to kill “every [Nlaka’pamux] man, woman and child they saw.” Snyder convinced these companies, led by Captain Graham, to allow him to advance upriver first, in an effort to broker access to the region.

Meanwhile at Kumsheen, warriors and chiefs assembled to develop their response to the approaching American military companies. Some people believed direct military confrontation was the only option, given several recent unprovoked attacks by Americans on Indigenous people in the region. Only a few months earlier at Okanagan Lake, miners had brazenly gunned down a group of Indigenous people for seemingly no reason at all.

Back downriver from Kumsheen, Captain Graham and his 1st lieutenant were killed in unclear circumstances, leaving Captain Snyder to carry out his strategy of negotiating access to the goldfields with Nlaka’pamux communities as he advanced upriver.

Truce Called

On 22 August, Captain Henry Snyder held council with the Nlaka’pamux Chief David Spintlum (Sexpínlhemx) and 11 gathered chiefs at Kumsheen. Snyder’s message at this council was simple. He told the Nlaka’pamux that they should grant American miners access to their goldfields or else they would be forced to confront additional American militias determined to access them by any means necessary. Many years later, Nlaka’pamux elder Mary Williams recalled Chief Spintlum’s decisive response to Snyder’s message:

"Chief (sic) Sexpínlhemx spoke up, asking, ‘What are you going to do?’ The Whites said that all the old people were going to be killed off — only the young woman were to be kept. ‘Stop right there!’ commanded Chief Cexpe’nthlEm. ‘End that talk right there! I am going to give you some land!’ Chief Cexpe’nthlEm stood up and stretched out his arms to the sundown and the sunrise, saying, ‘This side will be yours and this side will be my people’s. You are not to kill anyone...The White people agreed. They put down all their guns and shook hands with the Indian people."

The Fraser Canyon of British Columbia is the traditional territory of the Nlaka’pamux people.

To prevent bloodshed, the Nlaka’pamux nation led by Spintlum decided to accommodate the newcomers, who had arrived in their homelands without permission, disrupted their annual salmon fishery and laid claim to their resources. At the urging of Snyder, Nlaka’pamux communities throughout the Fraser Canyon flew white flags symbolizing the brokered peace. Ironically, in Nlaka’pamux culture, white was the colour of sickness, of the dead and of the spirit world.

In late August, Governor James Douglas travelled to the Fraser Canyon, accompanied by 35 armed men, “in hopes that early measures will be taken by Her Majesty’s Government, to relieve the country from its present perilous state.” However, the war was largely over by this point. After the council between Snyder and Nlaka’pamux chiefs, there was no further violence.

DID YOU KNOW?

On 14 April 2018, the descendants of Captain Henry Snyder and Chief David Spintlum — Dale Snyder and Cecil Salmon, respectively — met in Lytton, where their ancestors had convened 160 years prior to end the Fraser Canyon War. The New Pathways to Gold Society, a non-profit organization that forms partnerships with First Nations to, among other things, promote heritage, hosted the special event.

Consequences of the War

The Fraser Canyon War was a significant turning point in the Nlaka’pamux nation’s history. The encroachment of American miners on traditional territories marked only the beginning of successive waves of white British and Canadian settlers who did the same. However, by agreeing to a cessation of hostilities in the war, the Nlaka’pamux protected their people from further bloodshed, which could have been catastrophic. In 1927, a monument to Chief Spintlum (Cexpe’nthlEm) was erected at Kumsheen commemorating his role as a peacemaker in the conflict.

Another consequence of the Fraser Canyon War was the assertion of British sovereignty over the region that would eventually become the Canadian Province of British Columbia. Fearing that the miners might win the war and possibly encourage American takeover or annexation of the region, British officials led by Sir James Douglas responded by proclaiming sovereignty over the Fraser Canyon as part of the Crown Colony of British Columbia on 2 August 1858. On 20 July 1871, British Columbia became part of Canada.

The author would like to acknowledge Chief Byron Spinks of the Nlaka’pamux nation and Dr. Daniel Marshall of the University of Victoria for their assistance in the research and writing of this article.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom