The Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) was a militant Quebec independence movement that used terrorism to try and achieve an independent and socialist Quebec. FLQ members — or felquistes — were responsible for more than 200 bombings and dozens of robberies between 1963 and 1970 that left six people dead. Their actions culminated in the kidnapping of British trade commissioner James Cross and the kidnapping and subsequent murder of Quebec cabinet minister Pierre Laporte, in what became known as the October Crisis.

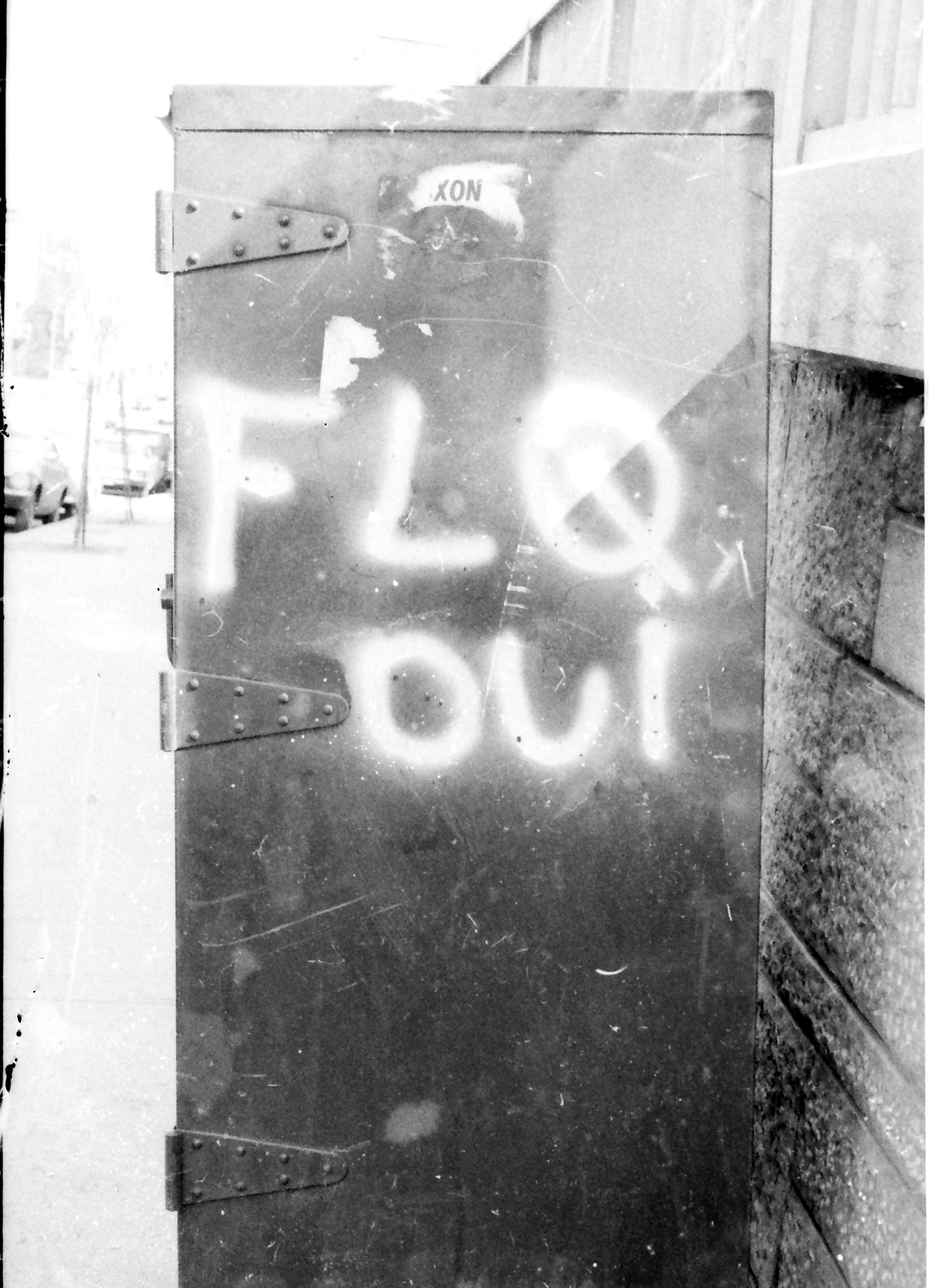

A Canada Post drop box (where letter carriers pick up their mail for delivery) in downtown Montreal in the summer of 1971, nine months after the October Crisis. Graffiti on the side reads "FLQ oui" (FLQ yes). (courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

Founding of the FLQ

The FLQ was founded in March 1963 by two Quebecers, Raymond Villeneuve and Gabriel Hudon, and a Belgian, Georges Schoeters, who had fought with the resistance during the Second World War.

Quebec was undergoing a period of profound political, social and cultural change at that time (see Quiet Revolution; Francophone Nationalism in Quebec), as well as rising unemployment. Members of the FLQ — or felquistes — were influenced by anti-colonial and communist movements in other parts of the world, particularly Algeria and Cuba. They shared a conviction that Quebec must liberate itself from anglophone domination and capitalism through armed struggle. Their objective was to destroy the influence of English colonialism by attacking its symbols. They hoped that Quebecers would follow their example and overthrow their colonial oppressors.

Their thinking — and their membership — was shaped by the more radical elements of earlier independence movements in Quebec. These included the Rassemblement pour l’Indépendance Nationale (founded in 1960); the Comité de libération nationale (founded in 1962), which promoted violence to achieve political ends; and the Réseau de résistance (also founded in 1962), which believed in protesting through vandalism.

The FLQ embraced symbols related to the Patriotes, members of the francophone Parti canadien, who contributed to the Rebellions of 1837–38 in Lower Canada. FLQ communiqués often included the figure of a habitant armed for the revolution. (See also Rebellion in Lower Canada; Louis-Joseph Papineau.)

The Beginnings of Violence

In April and May 1963, FLQ terrorists placed bombs in mailboxes outside three federal armories and in Westmount, a wealthy upper-middle-class anglophone area of Montreal. Wilfrid O’Neil, a nighttime security guard at a Canadian Armed Forces recruiting centre on Sherbrooke St. West in Montreal, was killed when a bomb exploded at the centre. The FLQ claimed responsibility. Sergeant-Major Walter Leja of the Armed Forces was seriously injured when he tried to neutralize a bomb in a Westmount mailbox. In October 1963, Gabriel Hudon, Raymond Villeneuve, Jacques Giroux and Yves Labonté pleaded guilty to manslaughter in the death of Wilfrid O’Neil. Their sentences range from 6 to 12 years in prison.

Within the FLQ, two wings emerged to supply the group with weapons and money. FLQ founder Gabriel Hudon’s younger brother, Robert, established the Armée de libération du Québec (ALQ). François Schirm, a Hungarian and former member of the French Foreign Legion, founded the Armée révolutionnaire du Québec (ARQ).

In August 1964, Schirm and four other members of the ARQ stole approximately $50,000 in cash and military equipment and committed an armed robbery at International Firearms, a Montreal gun store. During the robbery, a member of the ARQ killed employee Leslie McWilliams. Another employee, Alfred Pinisch, was mistaken for a robber and killed by police. The five ARQ members were arrested and convicted. Schirm and Edmond Guénette, the shooter, received the death penalty; two were sentenced to life imprisonment, and the other ARQ member was sentenced to 20 years in prison. These sentences provoked outrage within the FLQ.

Attacks Intensify

From 1965 to 1967, the FLQ associated itself with the activities of striking workers. While it did not succeed in infiltrating unions, it began to target companies that were involved in labour disputes. In May 1966, Thérèse Morin, a secretary at a shoe factory in Montreal, was killed when she opened a mail bomb.

Pierre Vallières, a former journalist who joined the FLQ in 1965, published his controversial autobiography, Nègres blancs d'Amérique, in 1968. He wrote it while he was jailed in New York for FLQ activities. The book depicts Quebec’s working class as a colonized people and argues that their conditions can only be improved through armed revolution.

Between October 1963 and April 1967, the FLQ published more than 60 issues of its newsletter, La Cognée (The Hatchet). It was replaced in November 1967 by the organization’s new journal, La Victoire, which began including instructions on how to make bombs.

Sergeant Robert Côté, to the right of the bomb disposal trailer used by the Montreal police, 1968.

In 1968, the FLQ began using larger and more powerful bombs. Their targets included a federal government bookstore, McGill University, the residence of Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau, the provincial Department of Labour, and the Eaton’s department store in downtown Montreal. In February 1969, a bombing at the Montreal Stock Exchange injured 27 people. In June 1970, an explosion at the National Defence Headquarters building in Ottawa killed communications supervisor Jeanne d'Arc Saint-Germain.

By 1970, more than 20 FLQ members were in prison for these acts of violence. In March 1969, Pierre-Paul Geoffroy was arrested in his Montreal apartment, where he had 161 sticks of dynamite and 35 cylinders of Pento-Mex, an industrial explosive. He pleaded guilty to 31 bombings between May 1968 and March 1969, including the explosion at the Montreal Stock Exchange. Faced with 129 charges, he received 124 life sentences plus 25 years; it was, at the time, the longest prison sentence ever levied in the British Commonwealth.

One of the most spectacular actions of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) involved the explosion of a bomb at the Montréal Stock Exchange in 1969. The photos show the damage caused by the explosion outdoors and inside the building. La Presse, February 4th, 1969, p. 7.

The October Crisis

In the fall of 1969, the remaining FLQ movement split into two distinct Montreal-based cells. The South Shore gang, which became the Chénier cell, was led by Jacques Rose; other members were his brother Paul Rose, Bernard Lortie and Francis Simard. The Liberation cell was led by Jacques Lanctôt; other members were his sister Louise Lanctôt and her husband, Jacques Cossette-Trudel, as well as Marc Carbonneau, Nigel Barry Hamer and Yves Langlois.

Shortly after 8 a.m. on 5 October 1970, three armed members of the Liberation cell, one disguised as a deliveryman, kidnapped British trade Commissioner James Cross from his home in Montreal. In exchange for the release of Cross, the cell issued seven demands, including $500,000, the release of 23 FLQ “political prisoners,” the broadcast and publication of the FLQ manifesto and safe passage to Cuba or Algeria. The cell gave the government 24 hours to comply with their demands. The government rejected the ultimatum but indicated that it was ready to negotiate.

British Trade Commissioner James Cross plays solitaire almost one month after his kidnapping in this photo released by his FLQ kidnappers in early November 1970.

On 10 October, Quebec justice minister Jérome Choquette announced that if Cross were released, the Liberation cell would be granted safe passage out of Canada; but none of their other demands would be met. Shortly thereafter, two masked members of the Chénier cell kidnapped Quebec Minister of Labour and Minister of Immigration Pierre Laporte while he was playing with his nephew on his front lawn in Saint-Lambert. (They had found his address in the phone book.)

The escalation of FLQ activities prompted Quebec premier Robert Bourassa — newly elected in April — to ask Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau to intervene. Trudeau, in turn, deployed the Armed Forces in Quebec and Ottawa and invoked the War Measures Act — the first and only time it has ever been used in a domestic crisis in Canada. Nearly 500 people were arrested without charge, including 150 suspected FLQ members.

Laporte was found dead in the trunk of a car on 17 October, a week after he had been kidnapped. An autopsy later revealed that he had been strangled. (Some media reports speculated that the strangulation may have been accidental — committed “in a moment of panic” according to one. But in his autobiography, Francis Simard wrote, “We killed him, it was not an accident.”)

On 18 October, warrants were issued for the arrest of Marc Carbonneau and Paul Rose. They were wanted in connection with the kidnapping and murder of Pierre Laporte. Police issued additional warrants for the other members of the Chénier cell — Jacques Rose, Bernard Lortie and Francis Simard — on 23 October. By 20 October, police had conducted 1,628 raids under the War Measures Act.

On 2 December, Jacques Cossette-Trudel and his wife Louise Lanctôt were arrested by Montreal police. By the next day, police had negotiated the release of James Cross in exchange for safe passage of all members of the Liberation cell, including Cossette-Trudel and Lanctôt and their infant daughter, to Cuba. After being held in a room in a Montreal North apartment for 59 days, Cross had lost 22 pounds but was otherwise in good health. He had not been harmed and described his captors as courteous. (See also October Crisis; The FLQ and the October Crisis Timeline.)

Aftermath of the October Crisis

Paul and Jacques Rose and Francis Simard were arrested on a farm southeast of Montreal on 28 December. They and Bernard Lortie were charged with the kidnapping and murder of Pierre Laporte on 5 January 1971. Paul Rose was sentenced to life imprisonment for kidnapping and murder; Francis Simard was sentenced to life for murder; Bernard Lortie was sentenced to 20 years for kidnapping; and Jacques Rose was acquitted of kidnapping and murder but was sentenced to eight years for being an accessory after the fact in the kidnapping of Laporte.

All the members of the Liberation cell, who were granted safe passage out of Canada in exchange for the release of James Cross, eventually returned to Canada. Jacques Cossette-Trudel and his wife Louise Lanctôt were sentenced to two years in prison on 7 August 1979 and were released on parole in April 1980. Jacques Lanctôt returned in January 1979. In addition to kidnapping charges in the case of Cross, he was also charged with conspiracy to kidnap Israeli trade commissioner Moshe Golem. Nigel Barry Hamer was sentenced to 12 months in jail on 21 May 1981. Marc Carbonneau was sentenced to 20 months in jail and three years probation on 23 March 1982. Yves Langlois, the final member of the Liberation cell to return from exile, was sentenced to two years in prison; he was paroled on 27 May 1983.

More than 100 FLQ members and sympathizers spent a cumulative 282 years in prison and 134 years in exile. Cut off from political, military and popular support, the FLQ ceased activities in 1971. Pierre Vallières renounced the FLQ and the use of terrorism and endorsed the Parti Québécois. He published The Assassination of Pierre Laporte in 1977. It focuses on the actions taken by police and government officials that, in Vallières’s estimation, contributed to the death of Laporte. Francis Simard’s autobiography, Talking It Out: The October Crisis from Inside, was published in 1987.

In Popular Culture

The National Film Board released two acclaimed documentaries about the October Crisis in 1973 — Action: The October Crisis of 1970 and Reaction: A Portrait of a Society in Crisis — both directed by Robin Spry. Michel Brault became the only Canadian ever to win the Best Director prize at the Cannes Film Festival with Les Ordres (1974). Based on the experiences of 50 people who were detained during the crisis, it is widely regarded as one of the best Canadian films ever made.

Pierre Falardeau, a staunch Quebec nationalist, created controversy in 1994 with the feature film Octobre. Adapted from Francis Simard’s autobiography, the film paints a sympathetic portrait of the Chénier cell members and their kidnapping and murder of Laporte. In 2000, CBC TV broadcast Black October (2000), a two-hour documentary about the crisis featuring interviews with Pierre Trudeau and James Cross. In 2006, it aired October 1970, an eight-part mini-series starring R.H. Thomson as Cross and Denis Bernard as Laporte. In 2010, for the 40th anniversary of the crisis, Radio-Canada broadcast a radio documentary about the crisis and its ramifications; it featured an interview with Pierre Laporte’s nephew, Claude Laporte, who witnessed his uncle’s kidnapping.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom