George Hislop, entrepreneur, advocate for gay and lesbian rights (born 3 June 1927 in Toronto ON; died 8 October 2005 in Toronto, ON). One of the most visible spokespersons for queer people throughout the 1980s, George Hislop was known as the “unofficial mayor of the Toronto gay community.” In 1971, he helped establish the Community Homophile Association of Toronto (CHAT). It became a major advocate for gays and lesbians as they struggled against police harassment and other forms of homophobia. In 1980, he ran for a seat on Toronto City Council — one of the first openly gay individuals to run for office. In 2001, Hislop became the lead plaintiff in a class action lawsuit against the federal government. It pressed for equal recognition of federal pension benefits for gay couples. The plaintiffs won in 2007, shortly after Hislop’s death.

Early Life

George Hislop was born in the west Toronto neighbourhood of Swansea. He was aware of his gay identity from a young age and never hid it from his parents. His friends would later recount him saying, “I never came out of the closet because I was never in it.”

In the 1940s, Hislop studied theatre at the University of Toronto. He later worked as a stage actor in Toronto and London, England, while also working at a bar. Back in Toronto in 1958, Hislop met Ronnie Shearer, who became his business partner and life companion.

Early Advocacy Work

George Hislop became more active in public advocacy after Ottawa decriminalized homosexuality in 1969. In 1970, one year after the Stonewall uprising in lower Manhattan, Hislop founded Gay Day, an event that evolved into Toronto’s Pride Week.

When the Community Homophile Association of Toronto (CHAT) was founded in 1971, Hislop became the group’s first director. Though modestly resourced, it had an ambitious mandate of organizing social activities, sending representatives to speak at high schools, monitoring court cases, and operating a volunteer-run 24-hour phone service for public education and community support. It also sought to advance the cause of gay liberation by working within the Canadian legal system. CHAT held an office near Yonge and Wellesley and hosted public meetings at the Church of the Holy Trinity. It soon became the most active organization of its kind in Toronto.

Businessman

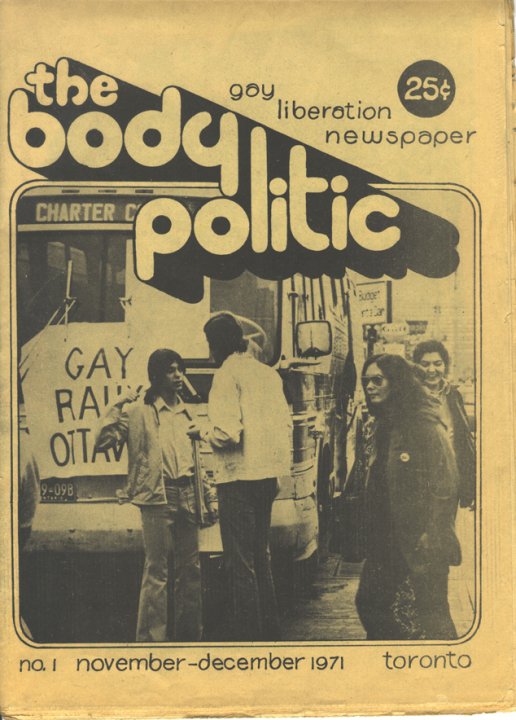

George Hislop operated various businesses in Toronto’s Gay Village, including Buddy’s bar and a restaurant called Crispin’s. Alongside Peter Maloney, Hislop was a partial owner of The Barracks, a BDSM-themed sex club in the Village. It was targeted by the police in their sporadic bathhouse raids in the late 1970s and early 1980s. (See Toronto Bathhouse Raids, 1981.) After one such raid in 1978, Hislop was charged with being the keeper of a “bawdy house.” Police also raided the offices of leading gay publication the Body Politic that year — a move that would provoke criticism from progressive mayor John Sewell.

Political Involvement

In 1980, Hislop ran for a seat on Toronto City Council as a representative of Ward 6. He gained several endorsements from the queer community, as well as from Sewell. Tensions around the subject of queerness were high at the time. This was partly because police had been sending outreach officers into high schools as part of a program called “Cop Shop,” in which they identified gays and lesbians as “deviate.” When progressive members of the school board and city council criticized the workshop, it provoked a conservative backlash. One downtown business owner organized a rally at City Hall, calling for the ouster of politicians who had “sold out to the gay lobby.”

Other police activities were generating friction with the community as well. In October 1979, police had broken into the home of a Black man named Albert Johnson and shot him in his bedroom. In turn, Hislop and Peter Maloney founded the Right to Privacy Committee to defend the victims of the bathhouse raids. The group also endorsed calls from the Black community for the laying of criminal charges against the officers and the creation of a civilian board to review police shootings.

Within this context, the Toronto Police Association was openly hostile to Hislop’s campaign. They distributed a memo to their members announcing a special project of putting up campaign signs for Hislop’s conservative rival, Gordon Chong. The police were also found to be distributing leaflets out of the waiting room of their station in Ward 6. The leaflets were reportedly from an organization called the League Against Homosexuals.

In an interview with the Toronto Star, Hislop said that he didn’t consider himself a “cop basher.” He noted that he had worked with the police to help address issues within the community. In fact, Hislop had previously helped the police arrest the murderers of Emmanuel Jaques, a shoeshine boy who was sexually assaulted and murdered in downtown Toronto in 1977 — an event that sparked major panic and outrage in the press.

Both Hislop and Sewell narrowly lost in the municipal election of November 1980. But Hislop’s campaign contributed to the growing visibility of the gay community. It also led to public criticism of police persecution of queer people and boosted Hislop’s public profile. He remained one of the most visible spokespersons for queer people throughout the 1980s — a decade in which the community was rocked by further police harassment, as well as the AIDS crisis.

Lawsuit vs. Federal Government

When his life partner Ronnie Shearer passed away in 1986, George Hislop was denied benefits from the Canada Pension Plan that heterosexual partners received. In 1999, the federal government changed the policy to include same-sex partners, but Hislop remained excluded because Shearer had died 13 years prior. Hislop then became the lead plaintiff in a lawsuit demanding that pension benefits be backdated to 1985, when the Charter of Rights and Freedoms took effect. The case finally succeeded at the Supreme Court of Canada in 2007, 17 months after Hislop passed away.

Legacy

Following George Hislop’s death, several members of the community recalled his wit, bravery and media savvy. He was often referred to as the “unofficial mayor of the Toronto gay community.” Hislop once joked that he didn’t like the title because “I’ve been a queen for years and I wasn’t going to be demoted to mayor.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom