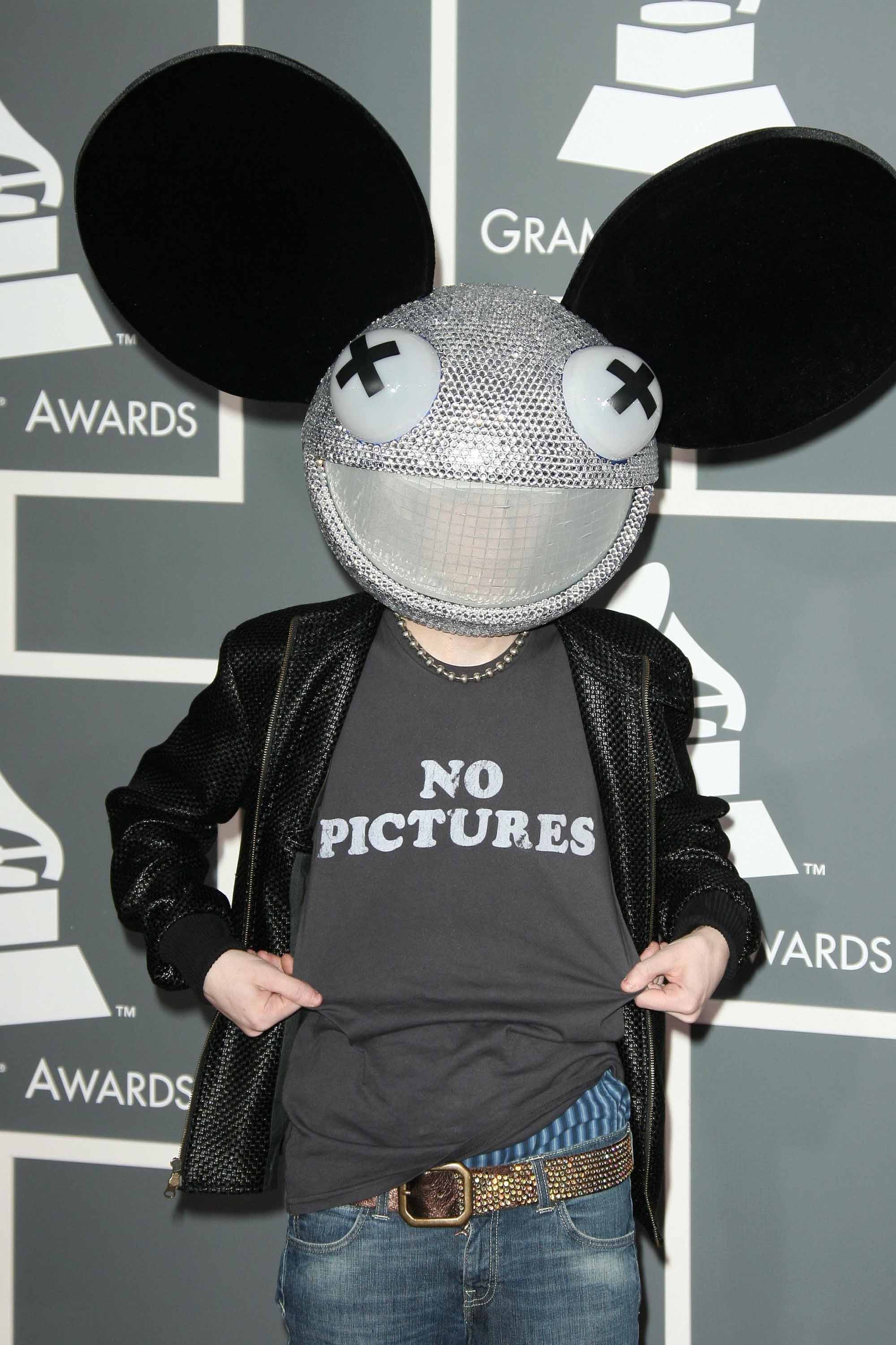

German Canadians and their descendants have left a significant mark on this country’s place names, economy, politics and culture. They have contributed to Canada’s development in various fields. Notable German Canadians include Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, Calgary mayor and Alberta premier Ralph Klein, actor and director Paul Gross, and electronic music producer Joel Thomas Zimmerman (Deadmau5).

Immigrant Origins

Canada’s Germans have come from virtually every east European country, Asiatic Russia, the United States, and Latin America. (German colonists had been migrating to Eastern Europe since the Middle Ages and to colonial America since 1683.) Canada’s main source of Germans was Russia — especially from the Volga, the Black Sea coast and Volhynia. The next largest number came from Austria-Hungary, especially Galicia and the colonies of the so-called Danube Swabians along the Danube River between Austria and Romania. Transylvanian Saxons arrived as labour migrants in the 1920s and refugees in the 1950s. The remaining east European origins were Czechoslovakia, Romania, Poland and the Baltic lands.

Germans arrived in Canada with such diverse citizenships as Austrian, Swiss, Luxembourgian, Hungarian, Russian, French and American; with a variety of regional identities, such as Palatine, Bavarian, Saxon, Burgenländer, Sudeten, Danube Swabian, Baltic, Alsatian and Pennsylvania Dutch; and with such religious allegiances as Mennonite, Hutterite, Lutheran, Roman Catholic, Baptist, Moravian and Jewish. Their mother tongues included High German, Low German, Pennsylvania Dutch and numerous regional dialects. From their homelands and histories of previous migrations, German-speaking immigrants transplanted a mosaic of German cultures, including ancestral traits extinct in Germany as well as unique adaptations to non-German environments.

Immigration History

German immigration to Canada may be divided into six major cohorts: the first settlers to 1776; the cohort generated by the American Revolution from 1776 to 1820; immigration to Upper Canada (Ontario) from 1830 to 1880; immigration to western Canada from 1874 to 1914; immigration between the world wars; and immigration since 1945.

German Immigration to New France and Acadia

Prior to the British Conquest, circa 1760, Germans came to New France primarily in the service of the French military forces. Swiss guards were members of the first French expedition of 1604 to launch a colony in Acadia. Québec’s first recorded settler from Germany is Hans Bernhard from Erfurt, who bought land on Île d’Orléans in 1664. By 1760, an estimated 200 German families could be identified along the St Lawrence River — mainly families of soldiers, seamen, artisans and army doctors. Many of the Germans who rose to prominence in Québec between 1760 and 1783 as businessmen, doctors, surveyors, engineers, silversmiths and furriers had come with British militias from New England.

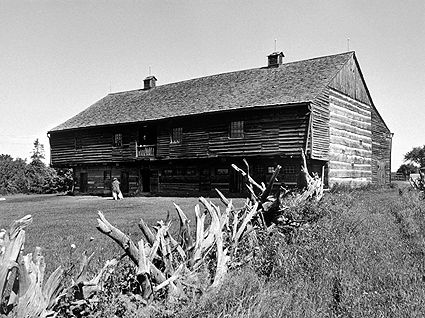

Canada’s oldest cohesive German settlement developed in Nova Scotia between 1750 and 1753, when 2,400 Protestant southwest German farmers and tradesmen landed with their families in Halifax. They were recruited by British agents to strengthen Britain’s position in Acadia vis-à-vis the French. In 1753, 1,400 of these Germans started the nearby community of Lunenburg. Although arriving with no marine skills, they became expert fishermen, sailors and boat builders by the next generation. In the 1760s, land grants attracted some additional 1,000 Germans from New England and Germany to Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley.

After 1752, the Moravian church of Herrnhut extended its mission to Inuit communities in Northern Labrador. From eight coastal stations, German Moravians served the Inuit until the 1960s as educators, employers, traders, judges, doctors, music teachers and lexicographers. By creating a written Inuktitut alphabet and dictionary, they helped preserve Inuit language and cultural identity.

German Loyalists after the War of Independence

The American Revolution triggered the emigration of Loyalists. Among these, Germans were the largest group of non-British descent, constituting between 10 and 20 per cent of the refugees fleeing to Canada by 1786. In Upper Canada, the German Loyalists’ share was an estimated 40 per cent. Arriving as early as 1776, most of these Germans were the children of emigrants who left the Palatinate (Bavaria) and adjoining regions for New York, where they were embroiled in the politics of their neighbouring Irish Loyalist landlords.

To suppress the American Revolution, Britain contracted in various German states for some 30,000 auxiliary troops. Of these “Hessians” (so called since most were from Hessian states), an estimated 2,400 remained in Canada post conflict. They had a significant cultural and demographic impact on Canadian society by the mere fact that they accounted for 3 to 4 per cent of Canada’s entire male population in 1783. In the Lower Canada towns (Québec) where the Hessians were billeted, they married local girls, fathered large families and assimilated rapidly.

Some of these German Loyalists helped settle other German families. One such example is George Pozer, a New York grocer originally from Wilstedt (Baden-Württemberg) who moved with his family to Québec in 1785. After having earned a fortune in trade, he purchased three seigneuries. To promote the growth of his seigneurie of D’Aubert-Gayon in Nouvelle-Beauce, he recruited nearly 200 settlers from his native village to come farm hemp. The town of Saint-Georges-de-Beauce was named in his memory.

In 1794, William Moll Berczy, a German land speculator and artist, became the co-founder of York (a forerunner of Toronto) when he started a gigantic colonization venture in Markham Township. With 190 immigrants recruited in Germany, he hewed a road through the virgin forest that became Toronto's Yonge Street, cleared land, cultivated fields, erected a church and a school, and built a model settlement whose "German Mills" became widely known. The enterprise disbanded in 1803 when the Executive Council of Upper Canada, distrusting Moll Berczy's motives as those of an "alien upstart" (to quote Paul Robert Magocsi in the Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples), declared his grant invalid.

Mennonite Immigration to Ontario

On their heels came Mennonites from Pennsylvania. These pacifist Anabaptist farmers fled the fervour of American nationalism and sought land for their growing population. Preferring cohesive settlement, they acquired a huge tract in Waterloo County. Through chain migration they transplanted their families, co-religionists and Pennsylvania-German culture. Isolating themselves from British immigrants while attracting some 50,000 newcomers from Germany between the 1830s and 1850s, their Waterloo County colony with a hub community named Berlin (in 1916 renamed Kitchener) developed into an area of concentrated German settlement. From there, German settlement spread to Perth, Huron, Bruce and Grey Counties. In the 1860s, the American Civil War diverted America-bound Germans to agricultural lands in the upper Ottawa Valley. By 1891, there were 12,000 Prussians living on both sides of the river, namely in the townships of Mulgrave-et-Derry, Renfrew and Pontiac.

German Settlement in the West

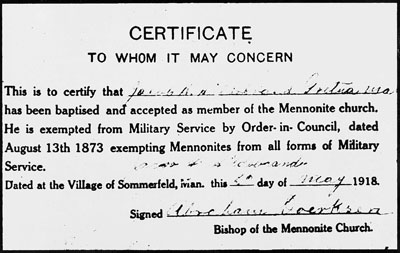

Of western Canada's 152,000 German pioneer settlers by 1911, more than half came from eastern Europe. Some 7,000 Mennonites from Russia, who had lost their military exemption, blazed the trail between 1874 and 1879. These attracted a continuous flow of co-religionists from Europe and the US to the Canadian prairies. Their successful block settlements in Manitoba demonstrated that farmers from the Russian steppes were particularly well adapted to prairie farming and that ethnically and denominationally homogeneous colonies proved a viable strategy for opening the West.

In British Columbia, the German presence dates back to the Cariboo Gold Rush of the 1860s, when Germans came with the first diggers from California, and subsequent groups of miners, to the Fraser River Valley. In Alberta, immigrants from Germany started homesteading in 1882. By 1892, a continuous influx of German Americans to Alberta and Saskatchewan mixed with colonists from virtually all German-speaking regions in Europe in joint German settlements. The largest were Saskatchewan's Roman Catholic St. Peter's and St. Joseph's colonies, founded in 1902 and 1904 respectively. Initiated by Benedictine monks from Minnesota and Illinois, their aim was to funnel Catholic German American newcomers into closed German-speaking settlements where their faith would be sheltered from the wider Protestant environment.

German Immigration between the World Wars

Despite the anti-German sentiment prevalent in the country at the end of the First World War in 1918, Canada admitted 1,000 Hutterites and 500–600 Mennonites fleeing intense American intolerance towards pacifists and germanophones. All but one of America's 18 Hutterite colonies, whose members were descendants of German-speaking immigrants to South Dakota from the Ukraine in the 1870s, entered Canada on the basis of an order-in-council of 1899 that granted them immunity from military service. However, in May 1919 Canada prohibited Hutterites and Mennonites until 1921, and nationals of former enemy countries until 1923.

Canada readmitted Germans in 1924 as “non-preferred” immigrants. This category restricted them to agricultural and domestic work. In January 1927, however, German nationals were promoted to the "preferred" class. Of Canada's 100,000 German immigrants from 1924 to 1930, 52 per cent came from eastern Europe and 18 per cent from the US. Agencies of the Canadian railways (Canadian Pacific Railway and Canadian National Railways) in co-operation with Mennonite, Baptist, Lutheran and Catholic immigration boards coordinated recruitment in Europe and settlement in Canada. Some 21,000 Mennonite refugees from Soviet Russia, barred from the US by quota legislation, formed Canada's largest group of ethnic German immigrants, in the 1920s.

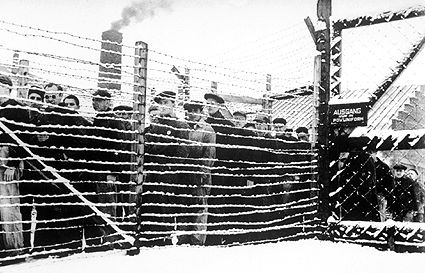

In the 1930s, Canada denied sanctuary to most Jewish refugee applicants from the Third Reich (see MS St. Louis), except for 972 from a batch of 2,300 shipped from British to Canadian internment camps in 1940 (see also Internment in Canada). Many of the 972 later made outstanding contributions to Canadian cultural life. Only one other German refugee group was admitted in 1939–40, also as a result of British pressures. These 1,043 Sudeten German Social Democrats were settled in the Tupper Creek wilderness of British Columbia and on abandoned railway land in northeastern Saskatchewan.

Postwar Policy: Refugees and Immigrants

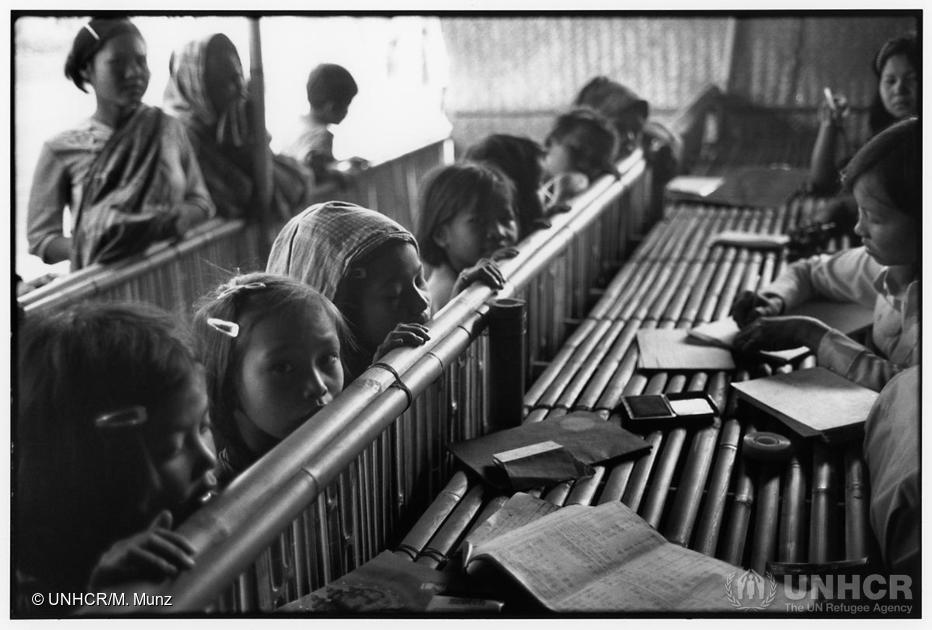

As part of its postwar policy of resettling displaced persons from Europe, Canada admitted some 15,000 Volksdeutsche (east European ethnic Germans) from 1947 to 1950. Most of these arrived with the help of the Canadian Christian Council for the Resettlement of Refugees, a government-authorized agency created by the Lutheran, Catholic, Mennonite and Baptist churches for the admission of ethnic German refugees excluded from the care of the United Nations.

The re-admission of Reichsdeutsche (German nationals) in 1950 opened the flood gates to a quarter of a million German newcomers by 1960, about one-third of were Russian-German, Volhynian-German, Danube Swabian, Baltic-German, Transylvanian Saxon, and Sudeten German refugees. Of the 400,000 German-speaking immigrants from 1945 to 1994, 5 per cent declared Austrian, and 5 per cent Swiss origin. Annual German arrivals in the 1960s fluctuated between 4,400 and 8,200, and in the 1970s and 1980s dropped to between 1,500 and 3,400. One-third to one-half of these newcomers returned to Europe or moved on to the United States.

Economic Life

Before 1945 most Germans were drawn to Canada by the prospect of farming on abundant and cheap land and preserving distinct religious lifestyles. They also played noticeable roles as entrepreneurs, professionals, artists and tradesmen in the beginning of Canadian urban life in Halifax, Montréal, Toronto, Hamilton, Berlin [Kitchener], Winnipeg, Calgary, Edmonton, Victoria and Vancouver. A high proportion of Canada's German business, professional, academic and artistic elites came from the US. In Hamilton, Winnipeg, Edmonton and Calgary, Germans were part of the early industrial labour force.

In the 1950s and 1960s, most German immigrants sought work in secondary industries. Although only 13 per cent of total immigration, they constituted over 19 per cent of Canada's skilled arrivals from 1953–63. Germans quickly attained levels of income matching or surpassing those of English and French Canadians. Benefiting from the large German immigrant market, German immigrants often seized opportunities for self-employment. Between 1950 and 1966, they launched 19 per cent of all new businesses started by immigrants. Some mushroomed into gigantic enterprises, as the Vancouver business successes of Helmut and Hugo Eppich and of Markham-based Frank Stronach (of Austrian background) attest. Having immigrated to Canada as mechanics, in 1953–54, the Eppichs and Stronach’s small auto parts and tool shops (established in the 1950s), developed into the multinational corporations EBCO and Magna International by the 1990s.

In some provinces, German presence has had a more visible impact than in others. For example, as of 2012, German Canadians represented about 22 per cent of the population in Manitoba, the third-largest percentage in Canada (Ontario and Alberta ranked first and second, respectively). There were 216,755 people declaring their ethnic origin as German. Many of them came from Russia or the former Soviet Union, and worked as everything from woodworkers to electricians. With the boom in the potash industry and the oil sands, Germans counted among the skilled immigrants employers sought in the face of labour shortages.

Community Life

From 1650 to 1950, almost two-thirds of Canada's 390,000 German-speaking immigrants came from outside Germany. However, the majority of Canada's 380,000 German-speaking people who immigrated from 1950 to 1994 were natives of Germany.

Diversity of origins has not prevented German-speaking immigrants from interacting as a singular community. From Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, to Waterloo County, Ontario, to Western Canada, German communities composed of mixed backgrounds formed the predominant pattern of German settlement, membership in churches, and voluntary ethnic associations, as well as in celebrating symbolic events such as German Day, Oktoberfest and Karneval.

While Germans from rural Eastern Europe tended to organize community life around their churches, immigrants from urbanized Germany established secular social clubs. German Canadian ethnic organizations originated with the Halifax High German Society (1786–91) and numbered over 600 by 1994. The oldest surviving German Canadian secular association is the German Society of Montreal, founded in 1835. The first nationally recognized umbrella organization was the Trans-Canada Alliance of German-Canadians (TCA). Founded in 1952, it counted 94 organizations in 1972 (with 20,000 active and 40,000 social members). Its successor is the German-Canadian Congress (GCC), founded in 1984, with some 550 affiliated organizations, including 130 churches, 100 German language schools, 20 senior citizens' homes, art associations, museums, theatres and credit unions, as well as several regional umbrella organizations created in 1994.

The GCC has assumed an advocacy role for the entire German Canadian community, including Mennonites and Hutterites, Austrians and Swiss, as well as anglophone and francophone Canadians of German-speaking background.

In 2010, GCC president Tony Bergmeier sparked controversy as he objected to the prominence to be given to the Holocaust exhibit in the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, slated to be opened in 2013. Other ethnic group representatives, such as the Ukrainian Canadian Congress, voiced similar opinions. The GCC press release argued that the museum should "recognize that human suffering is equal to all people. No suffering by one group of people can be more important than the suffering of others." Bernie Farber, then president of the Canadian Jewish Congress, stated he was surprised and saddened by the GCC objections. Wendy Lampert, writing for the National Post on 28 December, pointed out that "to suggest the Holocaust was just like any other genocide, undeserving of special recognition, is to ignore the reality of its impact on 20th-century society."

Religious and Cultural Life

The church — focus of community life in the rural homelands of the immigrants — remained the strongest influence on German community formation and maintenance in Canada until the Second World War. Church ministers acted as focal points for social cohesion and preservation of the German language and cultural heritage. Lutheranism has been the most popular German Canadian denomination, followed by Roman Catholicism and Mennonitism.

The cultural diversity of the German Canadian mosaic is reflected in its rich legacy. In Lunenburg, relics of 18th-century German culture are still noticeable. Canada's first illuminated Christmas tree, a medieval German custom, was erected in 1781 by General von Riedesel, commander of the German troops in North America. Physicians, artists and musicians from among his troops introduced professional standards in their respective arts to the Québec society of the day.

The Germans' love of music is reflected in the choirs, musicians, conductors and orchestras they started in many Canadian cities (see German Music in Canada). Since the early 19th century, such German Canadian artists as William Berczy, Peter Rindisbacher, and Otto R. Jacobi have enriched Canadian culture. Today, German Canadians are found among internationally acclaimed architects (Eberhard Zeidler), scientists (Gerhard Herzberg and John Polanyi), and space engineers (Claus Wagner Bartak).

The German-language press dates to the Halifax Neu-Schottländischer Calender (1788–1801). By 1867, 18 German-language papers appeared in Southwestern Ontario. The oldest continuously published paper is Mennonitische Rundschau. The Winnipeg-based Nordwesten (1889–1969) and the Regina Courier (1907–69) became the chief non-denominational papers with a national circulation. In 1970 they merged to become the Kanada Kurier.

Since 1900, an enduring endeavour to maintain German culture has been the German Saturday School. Initiated and funded by churches, clubs and parents, the schools have operated on school-free Saturday mornings for 2½–3 hours by teacher volunteers. In the early 1970s, the TCA coordinated a national network of 106 Saturday schools with 10,240 students. Enrolment has since declined, and German is increasingly taught to students of non-German-speaking background.

Cultural Conservation

Before the First World War, German Canadians did not question the compatibility of their customs and traditions with Canadian life, and Anglo-Canadian officials confirmed the affinity of German traits and values with their own on numerous occasions. The First World War changed all that. Overnight, Germans became Canada's most vilified enemy aliens. Charged with treason and sedition, although no charge was ever proven, many were economically ruined and socially ostracized. Unruly mobs were allowed to attack them and their properties in cities across the country. The Wartime Elections Act of September 1917 disenfranchised all German Canadians naturalized after March 1902. Clubs and associations were dissolved, German schools closed, German-language papers suppressed, and towns with such names as Berlin, Ontario, renamed. More than 2,000 immigrants from Germany were interned. Trauma from the First World War caused many German Canadians to camouflage their identity as Dutch, Scandinavian, or Russian. Long after the war, attribution of wartime characteristics continued. During the Second World War, the Canadian government arrested and interned 837 German Canadian farmers, workers and club members who were denounced or deemed disloyal. Again, cultural activities ceased almost completely.

After 1945, the recovery of ethnic confidence seemed problematic enough without the postwar revelations of the atrocities committed by the Nazi regime. In 1964, Maclean's characterized German Canadians to be "almost painfully unassertive." Postwar surveys found more than one-third of German immigrants eager to jettison their identity in favour of "Canadianism." Census data confirm that German Canadians have been abandoning their mother tongue at a rate superseded only by Scandinavian-, Dutch-, Flemish- and Gaelic-speaking immigrants.

Bilateral Relations between Canada and Germany

Canada and Germany maintain a close, friendly relationship that is visible in several areas: international cooperation, trade and investment, cultural life and higher education. The two countries work together to defend the values they hold in common, such as human rights, democracy and international security. The fact that both countries have experience with federalism has led to cooperative agreements between Canadian provinces and German Länder.

In the business sector, Germany is Canada’s eighth largest export market (in 2013, Canadian exports to Germany totalled nearly $3.5 billion) and its tenth largest foreign direct investor (with $11.7 billion in assets for the year 2012 alone).

In 1975, a cultural agreement was signed between Canada and Germany. A number of German universities offer Canadian studies programs, and interuniversity agreements have facilitated the creation of more than 200 exchange programs between German and Canadian universities.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom