War Fever

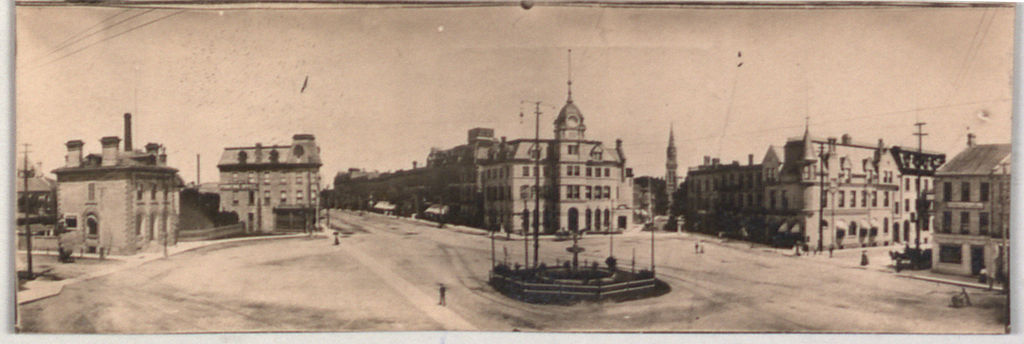

At the outbreak of the First World War in the summer of 1914, patriotic fervour gripped Guelph. The community expressed its enthusiasm with military parades, the display of bunting and Union Jack flags in the downtown core, and concerts and rallies in Exhibition Park. Shop windows displayed photographs of King George V and Lord Kitchener, the British secretary of state for war. The photographs would eventually be accompanied by war maps that allowed passersby to keep informed of activity on the Western Front. Mayor Samuel Carter praised Canadian soldiers who would be involved in what was being termed a fight for civilization.

The ambience of war was everywhere. Veteran soldiers who were too old for active duty held a meeting at the Armoury, Guelph’s military installation, and passed a motion to offer their services to Sam Hughes, the federal minister of militia and defence. At Guelph General Hospital, the senior nursing matron requested the names of nurses who would be willing to volunteer for the Canadian Army Medical Corps. Nurses also donated a day’s pay toward a national fundraiser for the purchase of a hospital ship. At Guelph city hall, representatives of Wellington County farmers who had initially agreed to send a shipload of oats to England decided on a cash donation instead.

A restaurant and confectioner called The Kandy Kitchen offered patrons “Shot and Shell” ice-cream sundaes, and a dessert called “British Dreadnought,” the term used for Royal Navy battleships. The Guelph Rifle Association offered men and boys free shooting lessons. Volunteers representing several women’s organizations, including the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE), the Women’s Canadian Club, and various church groups, canvassed the city collecting donations for war-related charities. The Guelph Evening Mercury newspaper noted that people in working-class wards gave proportionately more than residents of more affluent neighbourhoods.

Recruits

Recruiting was brisk in the early weeks. Eager young men lined up to enlist in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), looking forward to an adventure. One such volunteer was 17-year-old Wilfrid Laurier Callander. He was rejected because he was underage, and his chest didn’t meet the measurement required by army regulations. Callander spent the months before his 18th birthday exercising to build up his chest muscles. He was accepted on his second try.

At 36, George Thomas Ryder was twice Callander’s age. Born in England, Ryder had served with the British Army in the South African War before immigrating to Canada and settling in Guelph, where he worked in a foundry. By 1914, he was married and the father of four children. Against his wife’s wishes, Ryder enlisted in the CEF because he felt duty-bound to set an example for younger men. Wilfrid Callander survived the war; George Ryder didn’t — he was killed in the Battle of the Somme, near the village of Courcelette on 18 November 1916.

William Baxter, a guard at the Ontario Reformatory, was one of several British immigrants in Guelph who returned to England to join the British Army. Months before the CEF reached France, Baxter was killed in the First Battle of Flanders. Baxter was the first Guelphite to die in the war.

The numbers of volunteers declined as the war settled into a bloody stalemate with no end in sight. Large recruiting rallies were held in Guelph. From their church pulpits, clergymen called shame on young men not in uniform. Recruiting officers went into restaurants, movie theatres and other public places and admonished young women whose escorts weren’t soldiers. Corporal Joe Fitzgerald, a returned soldier who had been wounded, strode the streets of downtown Guelph, buttonholing youths in civilian clothes and demanding to know why they hadn’t signed up. He had an answer for every excuse. The dwindling number of volunteers across Canada eventually led to the passing of the Military Service Act in 1917, and the controversial federal policy of conscription.

OAC Officer Training Crisis

Shortly after the war began, the Ontario government instructed the Ontario Agricultural College (OAC) in Guelph to form an officer training corps. Acting president Charles A. Zavitz, a Quaker and pacifist, was opposed to military activity at the college. Understanding that his anti-war convictions made his position untenable, Zavitz submitted his resignation as acting president. James Duff, Ontario’s minister of agriculture, refused to accept the resignation due to Zavitz’s international reputation as a scientist. That drew the ire of Guelph Conservatives who accused Zavitz of disloyalty.

The situation became national news in November 1914, when a group from the South Wellington Conservative Association presented Duff with a petition demanding Zavitz’s removal. The Toronto Globe and the Farmer’s Advocate were among the publications that defended Zavitz. The crisis blew over in January 1915 with the return from sabbatical of OAC president Dr. George C. Creelman. The OAC then joined other post-secondary educational institutions in training officers.

Conscription Incidents

On 31 May 1917 — with the national debate over conscription deeply dividing Canadians — Guelph’s Trades and Labour Hall was the site of an open anti-conscription meeting organized by local Social Democratic Party members Lorne Cunningham and Albert Farley. A crowd of returned soldiers broke up the meeting. They made Cunningham and Farley sing “God Save the King,” and then paraded them up and down the main downtown street. The soldiers tossed the men in the air with blankets and made them shout “Three cheers for conscription.” Police constables did nothing until the soldiers threatened to destroy private property.

In the spring of 1917, confusion over a clause in the Military Service Act that exempted clergymen from conscription led to yet another incident in Guelph that made national headlines. A group of Protestant ministers complained to federal and military authorities that the students in the St. Stanislaus Novitiate, a Roman Catholic seminary on the outskirts of Guelph, were conscription evaders. On 7 June, military police in civilian clothes staged a late-night raid on the Novitiate. The commanding officer, Captain A.C. Macaulay, arrested three students. The operation came to an abrupt end when seminarian Marcus Doherty made a telephone call to his father, federal minister of justice Charles Doherty. The police left the premises without the students. The implications of the clandestine raid were hotly debated in the Canadian press. Not until after the war was over did a Royal Commission finally conclude that the seminary students were in fact exempted from conscription.

Enemy Within

From the beginning, there was a fear of enemy spies and saboteurs. Such fears were fuelled by stories — most, but not all of which were exaggerated — of American-based German agents crossing the border to disrupt Canada’s war effort. As in the rest of Canada, anti-German sentiment in Guelph was high. A street name was changed from Berlin to Foster. And the nearby community of Berlin, Ontario, changed its name to Kitchener. Immigrants from Germany and Eastern European countries that were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Germany’s ally, were derogatorily labelled “Austrians,” and were mistrusted. About 50 such “foreigners” in Guelph were rounded up and put on a train to a detainment camp. (See Prisoner of War Camps in Canada and Internment in Canada).

In keeping with the dictates of the War Measures Act, Guelph police chief Frederick Randall also confiscated wireless (radio) sets. Militiamen were posted to guard any potential target of enemy sabotage: the city’s water tower, the electric power station, war factories and railway bridges. The Mercury warned readers that sentries posted around the Armoury had orders to shoot intruders. Two members of the International Bible Students Association were arrested for possession of subversive literature. Sabotage was immediately suspected when Guelph’s municipal water supply was found to be contaminated. However, the cause of the contamination proved to be leaky pipes under cattle pasture. Guelphites were unaware that for several weeks in early 1916, notorious German saboteur Charles Respa was a prisoner in the Wellington County jail.

Casualty Telegrams

Although the federal government was initially unprepared for the large number of Canadian casualties overseas, it eventually developed a system by which families were informed by telegram of sons and husbands who had died; or were wounded, taken prisoner or reported missing. Casualties’ names were not to be released to the press until after next of kin had been notified. With so many names to be processed, mistakes were inevitable.

Judge Lewis M. Hayes of Guelph read in the Toronto News that a soldier named Stuart Hayes had been killed at Ypres, Belgium, in April 1915. The judge suspected that it might be his son, because the name of Stuart’s best friend, with whom he had enlisted, was also mentioned. Hayes wired the adjutant general in Ottawa, and received a reply that his son was missing in action. Then he was informed that Stuart was lying wounded in a hospital. Judge Hayes’ relief was short-lived, as Stuart died from his wounds in June. The Hayes family tragedy was played out like a drama in the pages of the Mercury.

In April 1917, Helen Pollington received a telegram informing her that her husband, George, was missing and presumed dead. In fact, George had been seriously wounded, but was alive. He was unconscious for days, and was transferred 11 times from one military hospital to another. He wrote to Helen, but she didn’t receive his correspondence. For nearly a year, Helen believed George was dead. Not until he arrived home in Guelph on 8 June 1918 did she learn the truth. She wasn’t the only next of kin to receive an inaccurate death notice.

Most of the time, however, the sad news carried by the telegrams was true. As the war dragged on and the casualty lists grew longer, people who had family members fighting overseas came to dread the appearance of the telegram boy on their street. At the sound of a knock on the door, the people of a household would immediately fear the worst. When neighbours visited for routine social calls, they would call and announce their presence out from the doorstep, rather than knock and cause undue alarm.

Women and War Shortages

Many women whose husbands were serving overseas endured difficulties. Mothers with small children often couldn’t go to work in war factories, and those who could were paid lower wages than male workers. Soldiers’ wives who received a government allowance could be stigmatized as recipients of “charity.” Some financially struggling mothers with children were obliged to move in with relatives. Wives whose husbands were absent were also targets of exploitation by unscrupulous businessmen. One housewife complained to the Mercury that as soon as her husband was gone, their landlord raised the rent. Another said a coal dealer cheated her out of fuel that her husband had paid for in advance.

Wartime shortages affected everybody, but none as much as women with families to care for. They had to make do with limited supplies of such staples as white flour, fresh meat and dairy products. The Mercury published “War Menus” showing how families could thrive on meals of salt cod, cornmeal porridge, shredded wheat biscuits, and “war bread” made from potato flour. Mothers turned their yards into vegetable gardens. Those who didn’t have yards, cultivated plots in vacant lots allocated by the city. Members of the Guelph Horticultural Society assisted people who had no agricultural experience. In 1917, the federal Department of Agriculture declared Guelph’s Vacant Lot Gardening Club “Best in the Dominion.”

A shortage of coal, the principal fuel for cooking and heating, was a problem throughout the war. The Guelph General Hospital once had to borrow a load from the Canadian Pacific Railway to keep patients from freezing. Resourceful mothers found ways to stretch scanty coal rations. On cold winter nights, the whole family would share a bed, kept warm by each others’ bodies and layers of pajamas and quilts. One woman in a working-class neighbourhood wrote an angry letter to the Mercury about large coal deliveries to wealthy homes that had multiple furnaces and fireplaces.

Aftermath

By the war’s end, the innocence of the Victorian and Edwardian eras had been swept away. Returned soldiers found that the jobs they’d given up to enlist were now held by non-British immigrants. At a meeting held in the Guelph Royal Opera House, they called for the deportation of “foreigners,” and a halt to immigration.

The Speedwell Convalescent Military Hospital was established to help rehabilitate disabled soldiers, but many other veterans with less visible physical and psychological damage received little or no assistance. Like the rest of Canada, Guelph was a place forever changed.

Reminders of the Great War can be seen in Guelph today. The city’s cenotaph in Trafalgar Park was designed by Alfred Howell and erected in 1927. Honour Rolls bearing the names of fallen soldiers can be viewed at places such as Guelph Collegiate Vocational Institute and at St. James the Apostle Anglican Church. The University of Guelph’s War Memorial Hall was constructed in 1924 to honour students of the Ontario Agricultural College who lost their lives in the war. McCrae House, the birthplace of John McCrae, author of “In Flanders Fields,” is a local museum. On 25 June 2015, a statue of McCrae was unveiled in front of the Guelph Civic Museum to mark the 100th anniversary of the poem’s first publication.

(See also: Wartime Home Front and Canadian Children and the Great War.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom