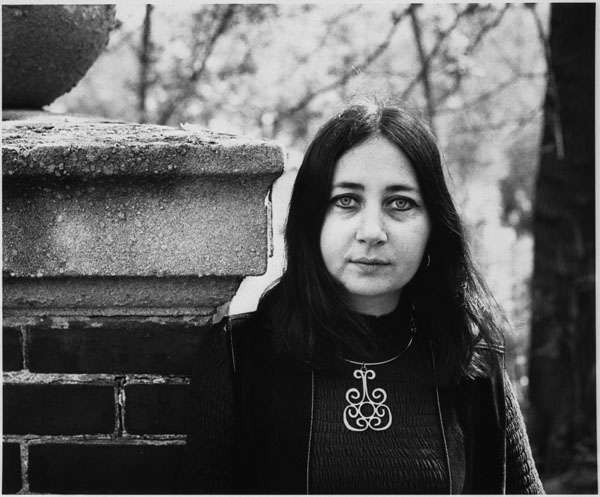

Gwendolyn MacEwen, writer (born 1 September 1941 in Toronto, ON; died 30 November 1987 in Toronto, ON). A sophisticated, wide-ranging and thoughtful writer, MacEwen began her career with the poetry collection The Drunken Clock (1961). In her many poetry collections, she displayed a commanding interest in magic and history as well as an elaborate and penetrating dexterity in her verse. By the end of her brief but productive career, MacEwen won two Governor General’s Awards as well as a Queen’s Silver Jubilee Award.

Early Life and Work

MacEwen’s first poem was published in The Canadian Forum, at the age of 17. Shortly after high school (she dropped out shortly before completing her degree), MacEwen self-published her first two works, Selah (1961) and The Drunken Clock (1961). In these early collections, she introduced her major themes and images, the most important being her muse character which she transformed over the course of her career from flying man into burning bird into the universal “you.” This muse, sometimes a voice, sometimes a character, sometimes a “shadowy presence,” created and inspired language and was the voice of order in MacEwen’s poems. MacEwen married poet Milton Acorn in February 1962, although their marriage ended in November that year.

In her first major collection, The Rising Fire (1963), MacEwen introduced one of her favourite metaphors — breakfast. In witty opposition to the Christian last supper, MacEwen makes breakfast the sacred meal of the day, the time when you commit to the day and when you have the muse of the sun close at hand. In “The Breakfast,” for instance, she writes:

place one hand before the sun and make it smaller,

hold the spoon in your hand up to the sky

and marvel at its relative size; comfort yourself

with the measures of a momentary breakfast table.

MacEwen never feared the different but sought it out and had an immense appetite for other societies’ mythology and culture. After returning from her first trip to the Middle East in 1962, she took a new direction. She completed her first novel Julian the Magician in 1963, expressing her fascination with the connection between the ancient practices of alchemy and magic. Teaching herself modern Arabic and Egyptian hieroglyphics, these languages began to inspire and inform her themes and metaphors. MacEwen’s second novel, King of Egypt, King of Dreams (1971), is a fictional retelling of the life of the ancient pharaoh and monotheist, Akhenaton. In the final chapter the narrator says farewell to her young, dead husband:

To hear your voice like the north wind

Is all I pray …

Call upon me by name forever and ever

And never shall it sound without reply.

In a single verse, MacEwen encompasses all the pain of mourning while asserting a commitment to living.

The Inner Deity

For every collection, MacEwen grouped poems thematically. The Shadow-Maker (1969), a complex and erudite collection, asserts that humans need to accept their small part in the universe and know that the only god lies within the self like a shadow which needs light and dark to exist. In “Poem” she writes, “It is not lost, tell me how can you lose it? / Can you lose the shadow which stalks the sun? / It feeds on mountains, it feeds on seas, / It loves you when you are most alone....What is here, what is with you now, is yours.”

Beginning In the 1960s, MacEwen wrote to poetic dramas for the CBC. At the same time, she was writing another collection of poetry, The Armies of the Moon (1972). In 1979, she was commissioned by the St. Lawrence Theatre Company to reimagine Euripedes’s The Trojan Women. MacEwen’s translation presented the Trojan women discovering their own powers and instinct for war. The play was originally staged in Toronto to critical acclaim and continues to be produced. By the age of 37 MacEwen had published six critically acclaimed books of poetry, two novels, a book of short stories, a memoir, Mermaids and Ikons, and had a play in production. She was invited to read her works across Canada and continued to write prolifically, including children’s stories and short narratives.

Cultures Clashing

Gwendolyn MacEwen’s engagement with Middle Eastern culture, mythology and language intersected her fascination with Thomas Edward Lawrence, a hero of the First World War. This inspired her most acclaimed collection, The T.E. Lawrence Poems (1982). Both Lawrence and MacEwen experienced early career success and were ambitious; both were enamored by the Arab world and believed in the notion of an “inner god.” For MacEwen, the political was personal: in order to find peace, each person must first face his or her enemy within. As such, MacEwen describes Lawrence’s inner struggle. Using Lawrence’s voice, which at points merges with the voice of the poet, she traces his childhood, his rise to power and his time in the Arabian deserts. MacEwen examines how his social class shaped a mind that British military culture would manipulate and disconnect from the soul. “The Parents” describes this process using Victorian sexual mores as metaphor:

Their necessary dark did not deceive me, their furtive

Victorian midnights did not deceive me.

I was the place they sold their souls in, and now I pay

For every breath I draw with the memory of their shame.

The poems in T.E. Lawrence also form a confession wherein Lawrence admits he deceived the people of the Arab world, failed his own country, denounced his own career, and that he was equally betrayed by others:

Everything sickened me; I had been betrayed from the moment

I was born. I betrayed the Arabs;

Everything betrays everything…?

The poems draw a powerful picture of opposing cultures and mythologies trapping an individual whose inner life demanded a different mythology in which to live.

Honours and Recognition

The Queen's Silver Jubilee Award, 1977 was given to Gwendolyn MacEwen for her contribution to the arts. Gwendolyn MacEwen served as writer-in-residence at several Canadian universities including the University of Western Ontario (1985) and twice at the University of Toronto (1986 and 1987). She was twice awarded the Governor General’s Award for Poetry — in 1969 for The Shadow-Maker and posthumously for Afterworlds in 1987. In 1993, Margaret Atwood and Barrie Callaghan edited comprehensive collections of MacEwen’s poetry: The Poetry of Gwendolyn MacEwen: The Early Years (Volume One) and The Later Years (Volume Two). Rosemary Sullivan’s biography Shadow Maker: The Life of Gwendolyn MacEwen (1995) won the Governor General’s Award for Non-fiction. Gwendolyn MacEwen Park, near the University of Toronto, is dedicated to her work and memory.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom