Early Life and Education

Richard Wagamese was born to Marjorie Wagamese and Stanley Raven of the Wabaseemoong Independent Nations. (See also First Nations.) His family followed the traditional way of life of the Ojibwe people, fishing, hunting and trapping. His first home, as he recalls in his essay “The Path to Healing,” in One Story, One Song (2011), “was a canvas army tent hung from a spruce bough frame.” As a toddler, he lived communally with his parents, siblings, his maternal grandmother, uncles, aunts and cousins.

When he was almost three years old, his parents left him and his three siblings alone in a bush camp for days while they were drinking in a town about 96 km away. Cold and hungry, the children managed to cross a frozen bay to seek shelter in the small railroad town of Minaki, where a provincial policeman spotted them and dropped them off at the Children’s Aid Society. From there, the siblings were taken away in what is known as the Sixties Scoop, a government program in Canada that aggressively “scooped” Indigenous children from their homes and placed them into foster care.

Both of Wagamese’s parents had also been removed from their families at a young age; they were survivors of Canada’s residential school system, which uprooted over 150,000 Indigenous children from their communities and forced them into church-run educational institutions. Wagamese would later write with forgiveness and understanding about the neglect he experienced from his parents as a result of the abuse and trauma they had suffered in the residential school system. This painful legacy would become a reoccurring theme throughout his body of work. (See also Truth and Reconciliation Commission.)

It was not until some 25 years after he was placed in foster care that Wagamese reunited with members of his birth family. His story closely resembles that of Garnet Raven, one of the narrators of his first novel, Keeper’n Me (1994), which tells the story of Raven’s reintroduction into Ojibwe culture in his 20s. “When I was three I disappeared,” Raven says. “Disappeared into foster homes and never made it back until I was twenty-five.”

In his fiction and non-fiction, Wagamese wrote extensively about the profound difficulties he experienced growing up in foster homes: “There had been moments when the pain and the confusion were so intense I felt as though my skin was peeling off,” he wrote in One Story, One Song. “There were beatings and martial discipline that scarred me. There was abandonment and neglect. There was a feeling of melancholy that I carried for years, a haunting I was at odds to explain.” He was shipped from one foster home to another throughout Ontario, often the only Indigenous kid in school, a constant outsider. As he put it in his essay “Born to Roam,” in One Story, One Song, “Family was an ever-changing set of faces.”

By the time he was 16 years old, Wagamese had dropped out of high school and was living on the streets, or with friends, doing whatever he could to survive. It was around this time that he began his literary education. “During my late teens and early twenties, I practically lived in libraries,” Wagamese wrote in the essay, “Beyond the Page” in One Story, One Song. While accepting the Writers’ Trust of Canada’s Matt Cohen Award in 2015, he reiterated how his reading as a young man shaped him into the writer he would become: “The only thing I’ve taken is the open opportunity that lay between the open covers of a book,” he said. “And I read and I read, and by sheer volume alone, I found out what a good sentence was and how a strong paragraph is constructed and how a great narrative arc is carried through the course of a long and lengthy story.”

Wagamese continued to live on the streets for a number of years, struggling with alcohol, drugs and post-traumatic stress disorder from the abuse and alienation that had marked his young life. He spent time in jail, lived all over Canada and worked countless jobs. “At times I have been a tree planter, a ditch digger, sugar beet picker, farm hand, railroad crew labourer, dish washer, fish cleaner, marina helper and a big rig washer,” he wrote in an essay for the Yukon News on 30 September 2009.

Writing Career

Richard Wagamese landed his first reporting job in 1979 with an Indigenous newspaper in Regina called The New Breed. He would go on to write a popular Indigenous affairs column for the Calgary Herald, and also work as a television and radio broadcaster. In 1991, he became the first Indigenous writer to win a National Magazine Award for column writing.

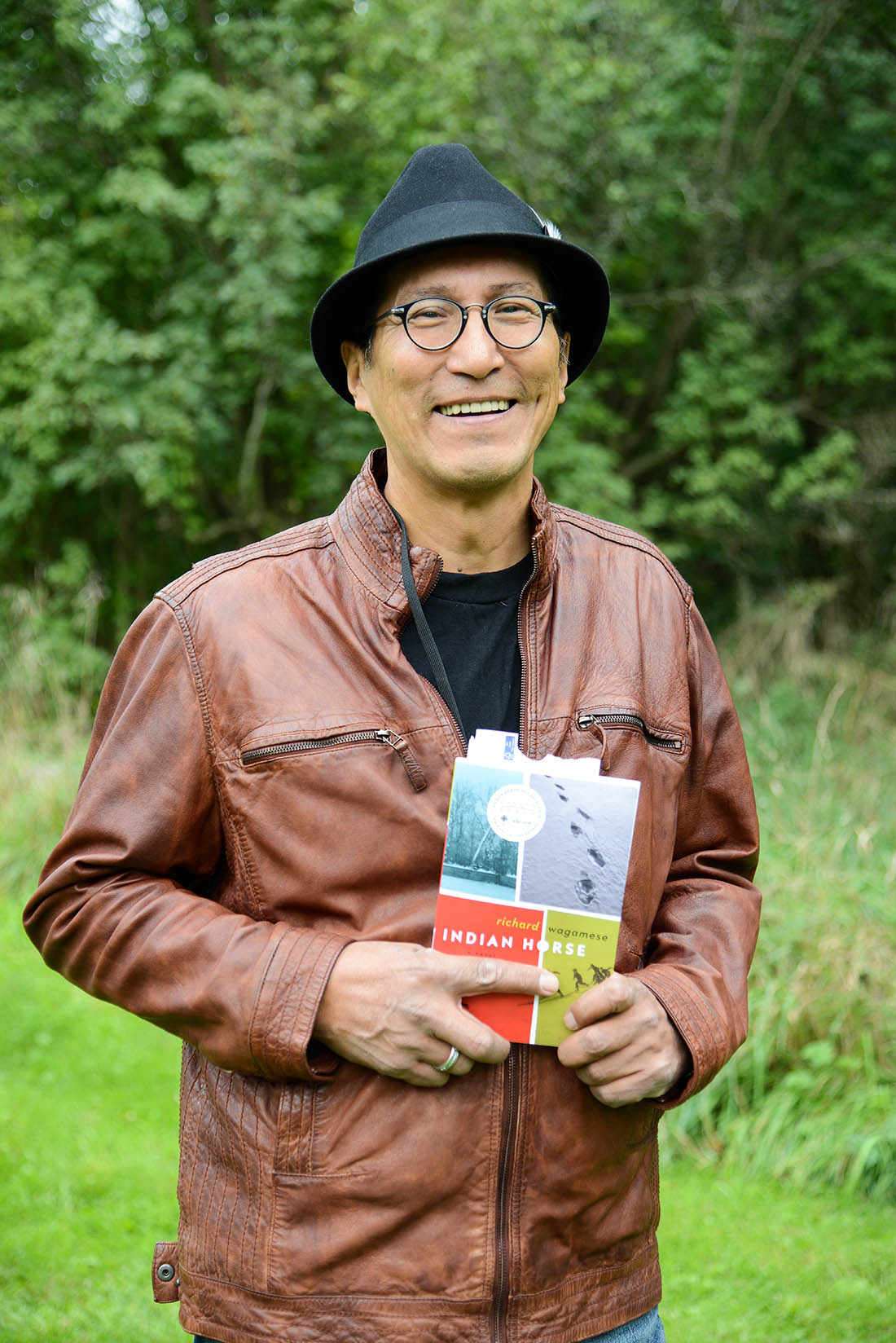

His debut novel, Keeper’n Me, was published in 1994 and won the Writers’ Guild of Alberta award for best novel. This marked the beginning of a prominent and prolific literary career. Wagamese went on to publish eight more novels, one collection of poetry and five works of non-fiction, including anthologies. His harrowing and darkly comic 2012 novel, Indian Horse, about a survivor of a residential school with an extraordinary gift for ice hockey, was a finalist on CBC’s Canada Reads, where it won the People’s Choice award. Indian Horse was adapted into a film in 2017 by writer Dennis Foon and producers Christine Haebler and Trish Dolman.

“People never ask me where I get the inspiration for my work and I really wish they would,” Wagamese said in a 2014 interview with the Globe and Mail. “The answer is long and complicated but shows my motivation to write and create stories. Simply and briefly put, I get my inspiration from the knowledge that there is someone out there in the world who is just like me — curious and desiring more and more knowledge of the world and her people. I write so that when they pick up one of my books there is an instantaneous connection, like we’re collaborating on the story.”

Wagamese also served as a writer for the federal government’s Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples in 1996.

In addition to writing, Wagamese lectured on creative writing at various universities, and was a faculty advisor on journalism at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology and Grant MacEwan Community College.

Death

Richard Wagamese died on 10 March 2017, at his home in Kamloops, British Columbia. He was 61 years old.

Wagamese’s close friend Shelagh Rogers, host of CBC Radio One’s The Next Chapter, told the Globe and Mail on 11 March 2017 that he was working on a sequel to Medicine Walk (2014) before he died. His last book Embers: One Ojibway’s Mediations (2016) was nominated for a Bill Duthie Booksellers’ Choice Award just one week before his death. In August 2018, a book Wagamese was working on before he died — Starlight — was released.

Wagamese leaves behind his two sons, Jason and Joshua; his grandchildren; his life partner, Yvette Lehman; and other family members and friends.

Awards and Acknowledgements

Richard Wagamese’s debut novel, Keeper’n Me won the Alberta Writers Guild Best Novel Award in 1995. Wagamese also won the Canadian Authors Association Award for his novel Dream Wheel in 2007 and the George Ryga Award for Social Awareness in Literature for his memoir, One Story, One Song, in 2011.

In 2012, he was the recipient of the National Aboriginal Achievement Award (now Indspire Award) for Media and Communications, and, in 2013, he received the Canada Council for the Arts Molson Prize and the Burt Award for First Nations, Métis and Inuit Literature.

Wagamese was given an Honorary Doctor of Letters degree from Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops in 2010, and he was the Harvey Stevenson Southam Lecturer in Journalism at University of Victoria in 2011.

Published Works

- Keeper’n Me (1994)

- The Terrible Summer (1996)

- A Quality of Light (1997)

- For Joshua: An Ojibway Father Teaches His Son (2002)

- Dream Wheels (2006)

- Ragged Company (2008)

- One Native Life (2008)

- One Story, One Song (2011)

- The Next Sure Thing (2011)

- Runaway Dreams (2011)

- Indian Horse (2012)

- Him Standing (2013)

- Medicine Walk (2014)

- Embers: One Ojibway’s Meditations (2016)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom