I turned on my computer the moment that Justice Murray Sinclair was due to present his report. I watched and sobbed as the news camera scanned the faces in the audience, many of them friends and colleagues. Every person there tried so hard to “keep it

together.” As they struggled to listen to Justice Sinclair without breaking down, each one of them let go a single tear and clenched their teeth. Many of them held eagle feathers. The eagles were busy that day. Justice Sinclair articulated what we all

knew to be true: “What took place in residential schools amounts to nothing short of cultural genocide.” As he summarized the report, we wept. We could not bear to hear it, but we knew it needed to be said. We could not bear the pain of hearing it because

then the reality would become so powerful. The honorary witnesses aged before the eyes of the camera as the words tumbled out onto the floor. Some of the MPs clenched their teeth too, desperately trying not to break down before the cameras.

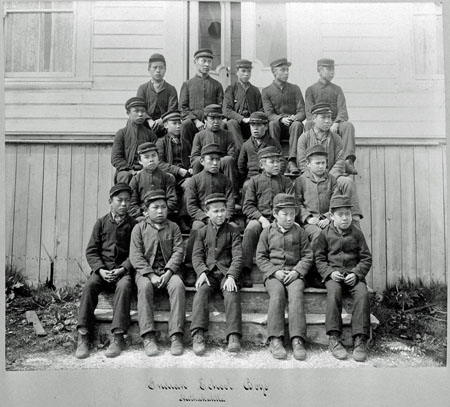

They were talking about my daddy, my gramma, my aunts, my uncles, some of my siblings, but not as they are today: adults with resources; adults who know they can seek redress. They were talking about my daddy as a little boy, my gramma as a little girl, my aunts and siblings as small children… I remember my siblings as small children and I wince, so fragile, so innocent, so eager to please, so... And I cannot bear listening, but I do not have the wherewithal to turn the computer off, so I sit, breaking apart and listening to something that is much more than painful.

I know what happened to my family now. I understand the fracturing and the willful rebuilding through the pain, clutching at every morsel of humour we have left, rebuking the desire to rage at the society that did this to us. I realize as I listen that the most painful thing is pushing out the rage, this amazing desire to hate, and pulling up the need for love, compassion and understanding. At the same time, I do not understand. I do not know how it is that another society can decide that the society in front of them is worthless, shameful and prohibitive. I do not understand. I do not understand how one group of people can attempt to erase the culture of another, ban it and punish the children for engaging it. But I do understand how the attempts to erase our culture, our language, our knowledge, very nearly destroyed our family. I understand the crippling effect this had on each and every one of us. I understand when my aunt tells me what my daddy said when he heard the apology from Prime Minister Harper: “At least I know it was not my fault.” I understand her when she said: “Bobby, how could you remember so much? I can’t remember anything.” I understand him when he answered her: “I couldn’t forget.”

I COULDN’T FORGET:

I couldn’t forget chasing the bus, wishing I could go to residential school with my relations. I couldn’t forget all the Sunday evenings that the yellow bus took away the kids who had to go to residential school. I couldn’t forget from year to year how the distance between us grew and grew, until it was a huge chasm of misunderstanding, loneliness and fracturing. For half my childhood, I had a huge extended family. By the time I was 11 years old, we stopped socializing with one another. It took us years to rebuild. First, we had to sober up, acknowledge one another without shame, and then we had to learn to love each other, despite all the disruption that our very existence seemed to be to everyone else in our world.

We all know what it is like to live surrounded by a society that does not want us. I know this intimately. I went to public school and was daily tormented for being “a dirty Indian” that “didn’t belong at this school.” This kept me chasing the residential school bus. It isolated me from the rest of my family. This isolation lasted a long time into my adulthood. As a child I knew everyone on the reserve, not so as an adult. I am coming to know my fellow villagers again. There are so many more now. There are so many young ones that I do not know and so I feel the fracture can’t be mended. But I can’t forget.

I can’t forget the sigh of relief when I saw the big yellow bus bringing the kids home from the school for the weekend. I have since learned that the kids at Tsleil-Waututh, who went to residential school just three miles down the road from the village, were lucky. The school was so close to home, a short bus ride, so they got to come home every weekend. So many kids went to other schools and did not see their families until they grew up. I feel the distance between us still and am horrified at the distance that must exist between a child and the parents after an absence of 12 formative, often abusive, years.

While my siblings were at residential school I found other friends. It was as simple as that. They came home and we just stared at one another. We went to Cultus Lake and, instead of playing together, we felt disconnected from each other. I came to dislike those cultural celebrations that only served to emphasize the fractured nature of our family. Residential school changed how we felt about our whole family — the extended family, the family that tried to engage in cultural celebrations as though all was right with the world. But it was not.

I was angry. Nothing in our world seemed to be right. I was isolated. Nothing in our world could plug the gap between us. It was not until we closed the first residential school in Sechelt — St. Augustine’s Indian Residential School shut down in 1975, after protests from the Native Alliance for Red Power at the behest of the children who complained of physical and sexual abuse — that the source of the fracturing loomed its awesome head. The removal of our children was what did it. I am angry about the removal.

I have heard that some people were not abused. Doesn’t matter — the majority were removed from their families. That is what mattered. Residential school did not hurt me directly, but I weep for my little lost sense of self in a large extended family when I was but 11 years old. I am not a residential school survivor — my family did not survive it, they had to overcome it. We had to rebuild our family. My daddy had 167 descendants and I know so few of them because of residential school. We no longer have the great gatherings our gramma hosted. The last one I remember was at Jackie Leech’s house. I was there, but stood askance of my father, watching my half-siblings, younger than myself, play and knowing that there was this “gossamer thin veil” — from Breath Tracks, by Jeannette Armstrong — separating us, keeping us from being a family, and that it was because I never had to get on that big yellow bus. In that way residential school hurt all of us — those that went and those that did not. Residential school hurt all of us, those that were abused and those that were not.

I am 65. I hope to restore our extended family before I leave. This is our cultural bundle and we need to pick it up. We need to bind ourselves to our extended families and begin again. As we lurch forward into a new future — different but the same — we will restore our greatness once again.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom